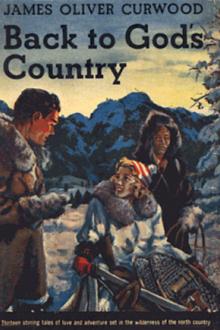

Back to God's Country and Other Stories - James Oliver Curwood (summer reads .txt) 📗

- Author: James Oliver Curwood

- Performer: -

Book online «Back to God's Country and Other Stories - James Oliver Curwood (summer reads .txt) 📗». Author James Oliver Curwood

From this ridge he could look straight into the north—the north where he was born. Only the Cree knew that for five nights he had slept, or sat awake, on the top of this ridge, with his face turned toward the polar star, and his heart breaking with loneliness and grief. Up there, far beyond where the green-topped forests and the sky seemed to meet, he could see a little cabin nestling under the stars—and Marie. Always his mind traveled back to the beginning of things, no matter how hard he tried to forget—even to the old days of years and years ago when he had toted the little Marie around on his back, and had crumpled her brown curls, and had revealed to her one by one the marvelous mysteries of the wilderness, with never a thought of the wonderful love that was to come. A half frozen little outcast brought in from the deep snows one day by Marie’s father, he became first her playmate and brother—and after that lived in a few swift years of paradise and dreams. For Marie he had made of himself what he was. He had gone to Montreal. He had learned to read and write, he worked for the Company, he came to know the outside world, and at last the Government employed him. This was a triumph. He could still see the glow of pride and love in Marie’s beautiful eyes when he came home after those two years in the great city. The Government sent for him each autumn after that. Deep into the wilderness he led the men who made the red and black lined maps. It was he who blazed out the northern limit of Banksian pine, and his name was in Government reports down in black and white—so that Marie and all the world could read.

One day he came back—and he found Clarry O’Grady at the Cummins’ cabin. He had been there for a month with a broken leg. Perhaps it was the dangerous knowledge of the power of her beauty—the woman’s instinct in her to tease with her prettiness, that led to Marie’s flirtation with O’Grady. But Jan could not understand, and she played with fire—the fire of two hearts instead of one. The world went to pieces under Jan after that. There came the day when, in fair fight, he choked the taunting sneer from O’Grady’s face back in the woods. He fought like a tiger, a mad demon. No one ever knew of that fight. And with the demon still raging in his breast he faced the girl. He could never quite remember what he had said. But it was terrible—and came straight from his soul. Then he went out, leaving Marie standing there white and silent. He did not go back. He had sworn never to do that, and during the weeks that followed it spread about that Marie Cummins had turned down Jan Larose, and that Clarry O’Grady was now the lucky man. It was one of the unexplained tricks of fate that had brought them together, and had set their discovery stakes side by side on Pelican Creek.

To-day, in spite of his smiling coolness, Jan’s heart rankled with a bitterness that seemed to be concentrated of all the dregs that had ever entered into his life. It poisoned him, heart and soul. He was not a coward. He was not afraid of O’Grady.

And yet he knew that fate had already played the cards against him. He would lose. He was almost confident of that, even while he nerved himself to fight. There was the drop of savage superstition in him, and he told himself that something would happen to beat him out. O’Grady had gone into the home that was almost his own and had robbed him of Marie. In that fight in the forest he should have killed him. That would have been justice, as he knew it. But he had relented, half for Marie’s sake, and half because he hated to take a human life, even though it were O’Grady’s. But this time there would be no relenting. He had come alone to the top of the ridge to settle the last doubts with himself. Whoever won out, there would be a fight. It would be a magnificent fight, like that which his grandfather had fought and won for the honor of a woman years and years ago. He was even glad that O’Grady was trying to rob him of what he had searched for and found. There would be twice the justice in killing him now. And it would be done fairly, as his grandfather had done it.

Suddenly there came a piercing shout from the direction of the river, followed by a wild call for him through Jackpine’s moose-horn. He answered the Cree’s signal with a yell and tore down through the bush. When he reached the foot of the ridge at the edge of the clearing he saw the men, women and children of Porcupine City running to the river. In front of the recorder’s office stood Jackpine, bellowing through his horn. O’Grady and his Indian were already shoving their canoe out into the stream, and even as he looked there came a break in the line of excited spectators, and through it hurried the agent toward the recorder’s cabin.

Side by side, Jan and his Indian ran to their canoe. Jackpine was stripped to the waist, like O’Grady and his Chippewayan. Jan threw off only his caribou-skin coat. His dark woolen shirt was sleeveless, and his long slim arms, as hard as ribbed steel, were free. Half the crowd followed him. He smiled, and waved his hand, the dark pupils of his eyes shining big and black. Their canoe shot out until it was within a dozen yards of the other, and those ashore saw him laugh into O’Grady’s sullen, set face. He was cool. Between smiling lips his white teeth gleamed, and the women stared with brighter eyes and flushed cheeks, wondering how Marie Cummins could have given up this man for the giant hulk and drink-reddened face of his rival. Those among the men who had wagered heavily against him felt a misgiving. There was something in Jan’s smile that was more than coolness, and it was not bravado. Even as he smiled ashore, and spoke in low Cree to Jackpine, he felt at the belt that he had hidden under the caribou-skin coat. There were two sheaths there, and two knives, exactly alike. It was thus that his grandfather had set forth one summer day to avenge a wrong, nearly seventy years before.

The agent had entered the cabin, and now he reappeared, wiping his sweating face with a big red handkerchief. The recorder followed. He paused at the edge of the stream and made a megaphone of his hands.

“Gentlemen,” he cried raucously, “both claims have been thrown out!”

A wild yell came from O’Grady. In a single flash four paddles struck the water, and the two canoes shot bow and bow up the stream toward the lake above the bend. The crowd ran even with them until the low swamp at the lake’s edge stopped them. In that distance neither had gained a yard advantage. But there was a curious change of sentiment among those who returned to Porcupine City. That night betting was no longer two and three to one on O’Grady. It was even money.

For the last thing that the men of Porcupine City had seen was that cold, quiet smile of Jan Larose, the gleam of his teeth, the something in his eyes that is more to be feared among men than bluster and brute strength. They laid it to confidence. None guessed that this race held for Jan no thought of the gold at the end. None guessed that he was following out the working of a code as old as the name of his race in the north.

As the canoes entered the lake the smile left Jan’s face. His lips tightened until they were almost a straight line. His eyes grew darker, his breath came more quickly. For a little while O’Grady’s canoe drew steadily ahead of them, and when Jackpine’s strokes went deeper and more powerful Jan spoke to him in Cree, and guided the canoe so that it cut straight as an arrow in O’Grady’s wake. There was an advantage in that. It was small, but Jan counted on the cumulative results of good generalship.

His eyes never for an instant left O’Grady’s huge, naked back. Between his knees lay his .303 rifle. He had figured on the fraction of time it would take him to drop his paddle, pick up the gun, and fire. This was his second point in generalship—getting the drop on O’Grady.

Once or twice in the first half hour O’Grady glanced back over his shoulder, and it was Jan who now laughed tauntingly at the other. There was something in that laugh that sent a chill through O’Grady. It was as hard as steel, a sort of madman’s laugh.

It was seven miles to the first portage, and there were nine in the eighty-mile stretch. O’Grady and his Chippewayan were a hundred yards ahead when the prow of their canoe touched shore. They were a hundred and fifty ahead when both canoes were once more in the water on the other side of the portage, and O’Grady sent back a hoarse shout of triumph. Jan hunched himself a little lower. He spoke to Jackpine—and the race began. Swifter and swifter the canoes cut through the water. From five miles an hour to six, from six to six and a half—seven—seven and a quarter, and then the strain told. A paddle snapped in O’Grady’s hands with a sound like a pistol shot. A dozen seconds were lost while he snatched up a new paddle and caught the Chippewayan’s stroke, and Jan swung close into their wake again. At the end of the fifteenth mile, where the second portage began, O’Grady was two hundred yards in the lead. He gained another twenty on the portage and with a breath that was coming now in sobbing swiftness Jan put every ounce of strength behind the thrust of his paddle. Slowly they gained. Foot by foot, yard by yard, until for a third time they cut into O’Grady’s wake. A dull pain crept into Jan’s back. He felt it slowly creeping into his shoulders and to his arms. He looked at Jackpine and saw that he was swinging his body more and more with the motion of his arms. And then he saw that the terrific pace set by O’Grady was beginning to tell on the occupants of the canoe ahead. The speed grew less and less, until it was no more than seventy yards. In spite of the pains that were eating at his strength like swimmer’s cramp, Jan could not restrain a low cry of exultation. O’Grady had planned to beat him out in that first twenty-mile spurt. And he had failed! His heart leaped with new hope even while his strokes were growing weaker.

Ahead of them, at the far end of the lake, there loomed up the black spruce timber which marked the beginning of the third portage, thirty miles from Porcupine City. Jan knew that he would win there—that he would gain an eighth of a mile in the half-mile carry. He knew of a shorter cut than that of the regular trail. He had cleared it himself, for he had spent a whole winter on that portage trapping lynx.

Marie lived only twelve miles beyond. More than once Marie had gone with him

Comments (0)