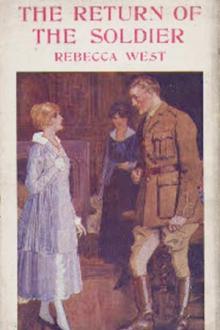

The Return of the Soldier - Rebecca West (most popular ebook readers txt) 📗

- Author: Rebecca West

- Performer: -

Book online «The Return of the Soldier - Rebecca West (most popular ebook readers txt) 📗». Author Rebecca West

“And now,” she said brightly as I put down my cup, “may I see Chris?” She had not a doubt of the enterprise.

I took her into the drawing-room and opened one of the French windows.

“Go past the cedars to the pond,” I told her. “He is rowing there.”

“That is nice,” she said. “He always looks so lovely in a boat.”

I called after her, trying to hint the possibility of a panic breakdown to their meeting:

“You’ll find he’s altered—”

She cried gleefully:

“Oh, I shall know him.”

As I went up-stairs I became aware that I was near to a bodily collapse; I suppose the truth is that I was physically so jealous of Margaret that it was making me ill. But suddenly, like a tired person dropping a weight that they know to be precious, but cannot carry for another minute, my mind refused to consider the situation any longer and turned to the perception of material things. I leaned over the balustrade and looked down at the fineness of the hall: the deliberate figure of the nymph in her circle of black waters, the clear pink-and-white of Kitty’s chintz, the limpid surface of the oak, the broken burning of all the gay reflected colors in the paneled walls. I said to myself, “If everything else goes, there is always this to fall back on,” and I went on, pleased that I was wearing delicate stuffs and that I had a smooth skin, pleased that the walls of the corridor were so soft a twilight blue, pleased that through a far-off open door there came a stream of light that made the carpet blaze its stronger blue. And when I saw that it was the nursery door that was open, and that Kitty was sitting in Nanny’s big chair by the window, I did not care about the peaked face she lifted, its fairness palely gilt by the March sunlight, or the tremendous implications of the fact that she had come to her dead child’s nursery although she had not washed her hair. I said sternly, because she had forgotten that we lived in the impregnable fort of a gracious life:

“O Kitty, that poor battered thing outside!”

She stared so grimly out into the garden that my eyes followed her stare.

It was one of those draggled days, common at the end of March when a garden looks at its worst. The wind that was rolling up to check a show of sunshine had taken away the cedar’s dignity of solid blue shade, had set the black firs beating their arms together, and had filled the sky with glaring gray clouds that dimmed the brilliance of the crocuses. It was to give gardens a point on days such as these, when the planned climax of this flower-bed and that stately tree goes for nothing, that the old gardeners raised statues in their lawns and walks, large things with a subject, mossy Tritons or nymphs with an urn, that held the eye. Even so in this unrestful garden one’s eyes lay on the figure in the yellow raincoat that was standing still in the middle of the lawn.

How her near presence had been known by Chris I do not understand, but there he was, running across the lawn as night after night I had seen him in my dreams running across No-Man’s-Land. I knew that so he would close his eyes as he ran; I knew that so he would pitch on his knees when he reached safety. I assumed naturally that at Margaret’s feet lay safety even before I saw her arms brace him under the armpits with a gesture that was not passionate, but rather the movement of one carrying a wounded man from under fire. But even when she had raised his head to the level of her lips, the central issue was not decided. I covered my eyes and said aloud, “In a minute he will see her face, her hands.” But although it was a long time before I looked again, they were still clinging breast to breast. It was as though her embrace fed him, he looked so strong as he broke away. They stood with clasped hands looking at one another. They looked straight, they looked delightedly! And then, as if resuming a conversation tiresomely interrupted by some social obligation, they drew together again, and passed under the tossing branches of the cedar to the wood beyond. I reflected, while Kitty shrilly wept, how entirely right Chris had been in his assertion that to lovers innumerable things do not matter.

AFTER the automobile had taken Margaret away Chris came to us as we sat in the drawing-room, and, after standing for a while in the glow of the fire, hesitantly said:

“I want to tell you that I know it is all right. Margaret has explained to me.”

Kitty crumpled her sewing into a white ball.

“You mean, I suppose, that you know I’m your wife. I’m pleased that you describe that as knowing ‘it’s all right,’ and grateful that you have accepted it at last—on Margaret’s authority. This is an occasion that would make any wife proud.”

Her irony was as faintly acrid as a caraway-seed, and never afterward did she reach even that low pitch of violence; for from that mild, forward droop of the head with which he received the mental lunge she realized suddenly that this was no pretense and that something as impassable as death lay between them. Thereafter his proceedings evoked no comment but suffering. There was nothing to say when all day, save for those hours of the afternoon that Margaret spent with him, he sat like a blind man waiting for his darkness to lift. There was nothing to say when he did not seem to see our flowers, yet kept till they rotted the daffodils which Margaret brought from the garden that looked like an allotment.

So Kitty lay about like a broken doll, face downward on a sofa, with one limp arm dangling to the floor, or protruding stiff feet in fantastic slippers from the end of her curtained bed; and I tried to make my permanent wear that mood which had mitigated the end of my journey with Margaret—a mood of intense perception in which my strained mind settled on every vivid object that came under my eyes and tried to identify myself with its brightness and its lack of human passion. This does not mean that I passed my day in a state of joyous appreciation; it means that many times in the lanes of Harrowweald I have stood for long looking up at a fine tracery of bare boughs against the hard, high spring sky while the cold wind rushed through my skirts and chilled me to the bone, because I was afraid that when I moved my body and my attention I might begin to think. Indeed, grief is not the clear melancholy the young believe it. It is like a siege in a tropical city. The skin dries and the throat parches as though one were living in the heat of the desert; water and wine taste warm in the mouth, and food is of the substance of the sand; one snarls at one’s company; thoughts prick one through sleep like mosquitos.

A week after my journey to Wealdstone I went to Kitty to ask her to come for a walk with me and found her stretched on her pillows, holding a review of her underclothing. She refused bitterly and added:

“Be back early. Remember Dr. Gilbert Anderson is coming at half-past four. He’s our last hope. And tell that woman she must see him. He says he wants to see everybody concerned.” She continued to look wanly at the frail, luminous silks her maid brought her as a speculator who had cornered an article for which there had been no demand might look at his damnably numerous, damnably unprofitable freights. So I went out alone into a soft day, with the dispelled winter lurking above in high dark clouds, under which there ran quick, fresh currents of air and broken shafts of insistent sunshine that spread a gray clarity of light in which every color showed sharp and strong. On the breast that Harrowweald turns to the south they had set a lambing-yard. The pale-lavender hurdles and gold-strewn straw were new gay notes on the opaque winter green of the slope, and the apprehensive bleatings of the ewes wound about the hill like a river of sound as they were driven up a lane hidden by the hedge. The lines of bare elms darkening the plains below made it seem as though the tide of winter had fallen and left this bare and sparkling in the spring. I liked it so much that I opened the gate and went and sat down on a tree which had been torn up by the roots in the great gale last year, but had not yet resigned itself to death, and was bravely decking its boughs with purple elm-flowers.

That pleased me, too, and I wished I had some one with me to enjoy this artless little show of the new year. I had not really wanted Kitty; the companions I needed were Chris and Margaret. Chris would have talked, as he loved to do when he looked at leisure on a broad valley, about ideas which he had to exclude from his ordinary hours lest they should break the power of business over his mind, and Margaret would have gravely watched the argument from the shadow of her broad hat to see that it kept true, like a housewife watching a saucepan of milk lest it should boil over. They were naturally my friends, these gentle, speculative people.

Then suddenly I was stunned with jealousy. It was not their love for each other that caused me such agony at that moment; it was the thought of the things their eyes had rested upon together. I imagined that white hawthorn among the poplars by the ferry on which they had looked fifteen years ago at Monkey Island, and it was more than I could bear. I thought how even now they might be exclaiming at the green smoke of the first buds on the brown undergrowth by the pond, and at that I slid off the tree-trunk and began walking very quickly down the hill. The red cows drank from the pond cupped by the willow-roots; a raw-boned stallion danced clumsily because warmth was running through the ground. I found a stream in the fields and followed it till it became a shining dike embanked with glowing green and gold mosses in the midst of woods; and the sight of those things was no sort of joy, because my vision was solitary. I wanted to end my desperation by leaping from a height, and I climbed on a knoll and flung myself face downward on the dead leaves below.

I was now utterly cut off from Chris. Before, when I looked at him, I knew an instant ease in the sight of the short golden down on his cheeks, the ridge of bronze flesh above his thick, fair eyebrows. But now I was too busy reassuring him by showing a steady, undistorted profile crowned by a neat, proud sweep of hair instead of the tear-darkened mask he always feared ever to have enough vitality left over to enjoy his presence. I spoke in a calm voice full from the chest, quite unfluted with agony; I read “Country Life” with ponderous interest; I kept my hands, which I desired to wring, in doeskin gloves for most of the day; I played with the dogs a

Comments (0)