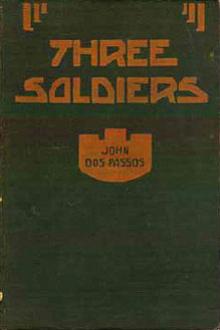

Three Soldiers - John Dos Passos (books to read fiction txt) 📗

- Author: John Dos Passos

- Performer: -

Book online «Three Soldiers - John Dos Passos (books to read fiction txt) 📗». Author John Dos Passos

“You look all in.”

“Not a bit of it. Oi just had a little hold up, that’s all, in a woodland lane. Some buggers tried to do me in.”

“What d’you mean?”

“Oi guess they had a little information…that’s all. Oi’m carryin’ important messages from our headquarters in Rouen to your president. Oi was goin’ through a bloody thicket past this side. Oi don’t know how you pronounce the bloody town…. Oi was on my bike making about thoity for the road was all a-murk when Oi saw four buggers standing acrost the road…lookter me suspicious-like, so Oi jus’ jammed the juice into the boike and made for the middle ‘un. He dodged all right. Then they started shootin’ and a bloody bullet buggered the boike…. It was bein’ born with a caul that saved me…. Oi picked myself up outer the ditch an lost ‘em in the woods. Then Oi got to another bloody town and commandeered this old sweatin’ machine…. How many kills is there to Paris, Yank?”

“Fifteen or sixteen, I think,”

“What’s he saying, Jean?”

“Some men tried to stop him on the road. He’s a despatch-rider.”

“Isn’t he ugly? Is he English?”

“Irish.”

“You bet you, miss; Hirlanday; that’s me…. You picked a good looker this toime, Yank. But wait till Oi git to Paree. Oi clane up a good hundre’ pound on this job in bonuses. What part d’ye come from, Yank?”

“Virginia. I live in New York.”

“Oi been in Detroit; goin’ back there to git in the automoebile business soon as Oi clane up a few more bonuses. Europe’s dead an stinkin’, Yank. Ain’t no place for a young fellow. It’s dead an stinkin’, that’s what it is.”

“It’s pleasanter to live here than in America…. Say, d’you often get held up that way?”

“Ain’t happened to me before, but it has to pals o’ moine.”

“Who d’you think it was?

“Oi dunno; ‘Unns or some of these bloody secret agents round the Peace Conference…. But Oi got to go; that despatch won’t keep.”

“All right. The beer’s on me.”

“Thank ye, Yank.” The man got to his feet, shook hands with Andrews and Jeanne, jumped on the bicycle and rode out of the garden to the road, threading his way through the iron chairs and tables.

“Wasn’t he a funny customer?” cried Andrews, laughing. “What a wonderful joke things are!”

The waiter arrived with the omelette that began their lunch.

“Gives you an idea of how the old lava’s bubbling in the volcano. There’s nowhere on earth a man can dance so well as on a volcano.”

“But don’t talk that way,” said Jeanne laying down her knife and fork. “It’s terrible. We will waste our youth to no purpose. Our fathers enjoyed themselves when they were young…. And if there had been no war we should have been so happy, Etienne and I. My father was a small manufacturer of soap and perfumery. Etienne would have had a splendid situation. I should never have had to work. We had a nice house. I should have been married….”

“But this way, Jeanne, haven’t you more freedom?”

She shrugged her shoulders. Later she burst out: “But what’s the good of freedom? What can you do with it? What one wants is to live well and have a beautiful house and be respected by people. Oh, life was so sweet in France before the war.”

“In that case it’s not worth living,” said Andrews in a savage voice, holding himself in.

They went on eating silently. The sky became overcast. A few drops splashed on the tablecloth.

“We’ll have to take coffee inside,” said Andrews.

“And you think it is funny that people shoot at a man on a motorcycle going through a wood. All that seems to me terrible, terrible,” said Jeanne.

“Look out. Here comes the rain!”

They ran into the restaurant through the first hissing sheet of the shower and sat at a table near a window watching the rain drops dance and flicker on the green iron tables. A scent of wet earth and the mushroom-like odor of sodden leaves came in borne on damp gusts through the open door. A waiter closed the glass doors and bolted them.

“He wants to keep out the spring. He can’t,” said Andrews.

They smiled at each other over their coffee cups. They were in sympathy again.

When the rain stopped they walked across wet fields by a foot path full of little clear puddles that reflected the blue sky and the white-and amber-tinged clouds where the shadows were light purplish-grey. They walked slowly arm in arm, pressing their bodies together. They were very tired, they did not know why and stopped often to rest leaning against the damp boles of trees. Beside a pond pale blue and amber and silver from the reflected sky, they found under a big beech tree a patch of wild violets, which Jeanne picked greedily, mixing them with the little crimson-tipped daisies in the tight bouquet. At the suburban railway station, they sat silent, side by side on a bench, sniffing the flowers now and then, so sunk in languid weariness that they could hardly summon strength to climb into a seat on top of a third class coach, which was crowded with people coming home from a day in the country. Everybody had violets and crocuses and twigs with buds on them. In people’s stiff, citified clothes lingered a smell of wet fields and sprouting woods. All the girls shrieked and threw their arms round the men when the train went through a tunnel or under a bridge. Whatever happened, everybody laughed. When the train arrived in the station, it was almost with reluctance that they left it, as if they felt that from that moment their work-a-day lives began again. Andrews and Jeanne walked down the platform without touching each other. Their fingers were stained and sticky from touching buds and crushing young sappy leaves and grass stalks. The air of the city seemed dense and unbreathable after the scented moisture of the fields.

They dined at a little restaurant on the Quai Voltaire and afterwards walked slowly towards the Place St. Michel, feeling the wine and the warmth of the food sending new vigor into their tired bodies. Andrews had his arm round her shoulder and they talked in low intimate voices, hardly moving their lips, looking long at the men and women they saw sitting twined in each other’s arms on benches, at the couples of boys and girls that kept passing them, talking slowly and quietly, as they were, bodies pressed together as theirs were.

“How many lovers there are,” said Andrews.

“Are we lovers?” asked Jeanne with a curious little laugh.

“I wonder…. Have you ever been crazily in love, Jeanne?”

“I don’t know. There was a boy in Laon named Marcelin. But I was a little fool then. The last news of him was from Verdun.”

“Have you had many…like I am?”

“How sentimental we are,” she cried laughing.

“No. I wanted to know. I know so little of life,” said Andrews.

“I have amused myself, as best I could,” said Jeanne in a serious tone. “But I am not frivolous…. There have been very few men I have liked…. So I have had few friends…do you want to call them lovers? But lovers are what married women have on the stage…. All that sort of thing is very silly.”

“Not so very long ago,” said Andrews, “I used to dream of being romantically in love, with people climbing up the ivy on castle walls, and fiery kisses on balconies in the moonlight.”

“Like at the Opera Comique,” cried Jeanne laughing.

“That was all very silly. But even now, I want so much more of life than life can give.”

They leaned over the parapet and listened to the hurrying swish of the river, now soft and now loud, where the reflections of the lights on the opposite bank writhed like golden snakes.

Andrews noticed that there was someone beside them. The faint, greenish glow from the lamp on the quai enabled him to recognize the lame boy he had talked to months ago on the Butte.

“I wonder if you’ll remember me,” he said.

“You are the American who was in the Restaurant, Place du Terte, I don’t remember when, but it was long ago.”

They shook hands.

“But you are alone,” said Andrews.

“Yes, I am always alone,” said the lame boy firmly. He held out his hand again.

“Au revoir,” said Andrews.

“Good luck!” said the lame boy. Andrews heard his crutch tapping on the pavement as he went away along the quai.

“Jeanne,” said Andrews, suddenly, “you’ll come home with me, won’t you?”

“But you have a friend living with you.”

“He’s gone to Brussels. He won’t be back till tomorrow.”

“I suppose one must pay for one’s dinner,” said Jeanne maliciously.

“Good God, no.” Andrews buried his face in his hands. The singsong of the river pouring through the bridges, filled his ears. He wanted desperately to cry. Bitter desire that was like hatred made his flesh tingle, made his hands ache to crush her hands in them.

“Come along,” he said gruffly.

“I didn’t mean to say that,” she said in a gentle, tired voice. “You know, I’m not a very nice person.” The greenish glow of the lamp lit up the contour of one of her cheeks as she tilted her head up, and glimmered in her eyes. A soft sentimental sadness suddenly took hold of Andrews; he felt as he used to feel when, as a very small child, his mother used to tell him Br’ Rabbit stories, and he would feel himself drifting helplessly on the stream of her soft voice, narrating, drifting towards something unknown and very sad, which he could not help.

They started walking again, past the Pont Neuf, towards the glare of the Place St. Michel. Three names had come into Andrews’s head, “Arsinoe, Berenike, Artemisia.” For a little while he puzzled over them, and then he remembered that Genevieve Rod had the large eyes and the wide, smooth forehead and the firm little lips the women had in the portraits that were sewn on the mummy cases in the Fayum. But those patrician women of Alexandria had not had chestnut hair with a glimpse of burnished copper in it; they might have dyed it, though!

“Why are you laughing?” asked Jeanne.

“Because things are so silly.”

“Perhaps you mean people are silly,” she said, looking up at him out of the corners of her eyes.

“You’re right.”

They walked in silence till they reached Andrews’s door.

“You go up first and see that there’s no one there,” said Jeanne in a businesslike tone.

Andrews’s hands were cold. He felt his heart thumping while he climbed the stairs.

The room was empty. A fire was ready to light in the small fireplace. Andrews hastily tidied up the table and kicked under the bed some soiled clothes that lay in a heap in a corner. A thought came to him: how like his performances in his room at college when he had heard that a relative was coming to see him.

He tiptoed downstairs.

“Bien. Tu peux venir, Jeanne,” he said.

She sat down rather stiffly in the straight-backed armchair beside the fire.

“How pretty the fire is,” she said.

“Jeanne, I think I’m crazily in love with you,” said Andrews in an excited voice.

“Like at the Opera Comique.” She shrugged her shoulders. “The room’s nice,” she said. “Oh, but, what a big bed!”

“You’re the first woman who’s been up here in my time, Jeanne…. Oh, but this uniform is frightful.”

Andrews thought suddenly of all the tingling bodies constrained into the rigid attitudes of automatons in uniforms like this one; of all the hideous farce of making men into machines. Oh,

Comments (0)