An Apache Princess - Charles King (readict books .TXT) 📗

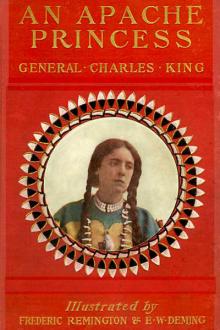

- Author: Charles King

- Performer: -

Book online «An Apache Princess - Charles King (readict books .TXT) 📗». Author Charles King

Plume would not say just what, but he would certainly have to stand court-martial, said he. Mrs. Plume shuddered more. What good would that do? How much better it would be to suppress everything than set such awful scandal afloat. The matter was now in the hands of the department commander, said Plume, and would have to take its course. Then, in some way, from her saying how ill the captain was looking, Plume gathered the impression that she had seen him since his arrest, and asked the question point-blank. Yes, she admitted,—from the window,—while she was helping Elise. Where was he? What was he doing? Plume had asked, all interest now, for that must have been very late, in fact, well toward morning. "Oh, nothing especial, just looking at his watch," she thought, "he probably couldn't sleep." Yes, she was sure he was looking at his watch.

Then, as luck would have it, late in the day, when the mail came down from Prescott, there was a little package for Captain Wren, expressed, and Doty signed the receipt and sent it by the orderly. "What was it?" asked Plume. "His watch, sir," was the brief answer. "He sent it up last month for repairs." And Mrs. Plume at nine that night, knowing nothing of this, yet surprised at her husband's pertinacity, stuck to her story. She was sure Wren was consulting or winding or doing something with a watch, and, sorely perplexed and marveling much at the reticence of his company commanders, who seemed to know something they would not speak of, Wren sent for Doty. He had decided on another interview with Wren.

Meanwhile "the Bugologist" had been lying patiently in his cot, saying little or nothing, in obedience to the doctor's orders, but thinking who knows what. Duane and Doty occasionally tiptoed in to glance inquiry at the fanning attendant, and then tiptoed out. Mullins had been growing worse and was a very sick man. Downs, the wretch, was painfully, ruefully, remorsefully sobered over at the post of the guard, and of Graham's feminine patients the one most in need, perhaps, of his ministration was giving the least trouble. While Aunt Janet paced restlessly about the lower floor, stopping occasionally to listen at the portal of her brother, Angela Wren lay silent and only sometimes sighing, with faithful Kate Sanders reading in low tone by the bedside.

The captains had gone back to their quarters, conferring in subdued voices. Plume, with his unhappy young adjutant, was seated on the veranda, striving to frame his message to Wren, when the crack of a whip, the crunching of hoofs and wheels, sounded at the north end of the row, and down at swift trot came a spanking, four-mule team and Concord wagon. It meant but one thing, the arrival of the general's staff inspector straight from Prescott.

It was the very thing Plume had urged by telegraph, yet the very fact that Colonel Byrne was here went to prove that the chief was far from satisfied that the major's diagnosis was the right one. With soldierly alacrity, however, Plume sprang forward to welcome the coming dignitary, giving his hand to assist him from the dark interior into the light. Then he drew back in some chagrin. The voice of Colonel Byrne was heard, jovial and reassuring, but the face and form first to appear were those of Mr. Wayne Daly, the new Indian agent at the Apache reservation. Coming by the winding way of Cherry Creek, the colonel must have found means to wire ahead, then to pick up this civil functionary some distance up the valley, and to have some conference with him before ever reaching the major's bailiwick. This was not good, said Plume. All the same, he led them into his cozy army parlor, bade his Chinese servant get abundant supper forthwith, and, while the two were shown to the spare room to remove the dust of miles of travel, once more returned to the front piazza and his adjutant.

"Captain Wren, sir," said the young officer at once, "begs to be allowed to see Colonel Byrne this evening. He states that his reasons are urgent."

"Captain Wren shall have every opportunity to see Colonel Byrne in due season," was the answer. "It is not to be expected that Colonel Byrne will see him until after he has seen the post commander. Then it will probably be too late," and that austere reply, intended to reach the ears of the applicant, steeled the Scotchman's heart against his commander and made him merciless.

The "conference of the powers" was indeed protracted until long after 10.30, yet, to Plume's surprise, the colonel at its close said he believed he would go, if Plume had no objection, and see Wren in person and at once. "You see, Plume, the general thinks highly of the old Scot. He has known him ever since First Bull Run and, in fact, I am instructed to hear what Wren may have to say. I hope you will not misinterpret the motive."

"Oh, not at all—not at all!" answered the major, obviously ill pleased, however, and already nettled that, against all precedent, certain of the Apache prisoners had been ordered turned out as late as 10 p. m. for interview with the agent. It would leave him alone, too, for as much as half an hour, and the very air seemed surcharged with intrigue against the might, majesty, power, and dominion of the post commander. Byrne, a soldier of the old school, might do his best to convince the major that in no wise was the confidence of the general commanding abated, but every symptom spoke of something to the contrary. "I should like, too, to see Dr. Graham to-night," said the official inquisitor ere he quitted the piazza to go to Wren's next door. "He will be here to meet you on your return," said Plume, with just a bit of stateliness, of ruffled dignity in manner, and turned once more within the hallway to summon his smiling Chinaman.

Something rustling at the head of the stairs caused him to look up quickly. Something dim and white was hovering, drooping, over the balustrade, and, springing aloft, he found his wife in a half-fainting condition, Elise, the invalid, sputtering vehemently in French and making vigorous effort to pull her away. Plume had left her at 8.30, apparently sleeping at last under the influence of Graham's medicine. Yet here she was again. He lifted her in his arms and laid her upon the broad, white bed. "Clarice, my child," he said, "you must be quiet. You must not leave your bed. I am sending for Graham and he will come to us at once."

"I will not see him! He shall not see me!" she burst in wildly. "The man maddens me with his—his insolence."

"Clarice!"

"Oh, I mean it! He and his brother Scot, between them—they would infuriate a—saint," and she was writhing in nervous contortions.

"But, Clarice, how?"

"But, monsieur, no!" interposed Elise, bending over, glass in hand. "Madame will but sip of this—Madame will be tranquil." And the major felt himself thrust aside. "Madame must not talk to-night. It is too much."

But madame would talk. Madame would know where Colonel Byrne was gone, whether he was to be permitted to see Captain Wren and Dr. Graham, and that wretch Downs. Surely the commanding officer must have some rights. Surely it was no time for investigation—this hour of the night. Five minutes earlier Plume was of the same way of thinking. Now he believed his wife delirious.

"See to her a moment, Elise," said he, breaking loose from the clasp of the long, bejeweled fingers, and, scurrying down the stairs, he came face to face with Dr. Graham.

"I was coming for you," said he, at sight of the rugged, somber face. "Mrs. Plume—"

"I heard—at least I comprehend," answered Graham, with uplifted hand. "The lady is in a highly nervous state, and my presence does not tend to soothe her. The remedies I left will take effect in time. Leave her to that waiting woman; she best understands her."

"But she's almost raving, man. I never knew a woman to behave like that."

"Ye're not long married, major," answered Graham. "Come into the air a bit," and, taking his commander's arm, the surgeon swept him up the starlit row, then over toward the guard-house, and kept him half an hour watching the strange interview between Mr. Daly, the agent, and half a dozen gaunt, glittering-eyed Apaches, from whom he was striving to get some admission or information, with Arahawa, "Washington Charley," as interpreter. One after another the six had shaken their frowsy heads. They admitted nothing—knew nothing.

"What do you make of it all?" queried Plume.

"Something's wrang at the reservation," answered Graham. "There mostly is. Daly thinks there's running to and fro between the Tontos in the Sierra Ancha country and his wards above here. He thinks there's more out than there should be—and more a-going. What'd you find, Daly?" he added, as the agent joined them, mechanically wiping his brow. Moisture there was none. It evaporated fast as the pores exuded.

"They know well enough, damn them!" said the new official. "But they think I can be stood off. I'll nail 'em yet—to-morrow," he added. "But could you send a scout at once to the Tonto basin?" and Daly turned eagerly to the post commander.

Plume reflected. Whom could he send? Men there were in plenty, dry-rotting at the post for lack of something to limber their joints; but officers to lead? There was the rub! Thirty troopers, twenty Apache Mohave guides, a pack train and one or, at most, two officers made up the usual complement of such expeditions. Men, mounts, scouts, mules and packers, all, were there at his behest; but, with Wren in arrest, Sanders and Lynn back but a week from a long prod through the Black Mesa country far as Fort Apache, Blakely invalided and Duane a boy second lieutenant, his choice of cavalry officers was limited. It never occurred to him to look beyond.

"What's the immediate need of a scout?" said he.

"To break up the traffic that's going on—and the rancherias they must have somewhere down there. If we don't, I'll not answer for another month." Daly might be new to the neighborhood, but not to the business.

"I'll confer with Colonel Byrne," answered Plume guardedly. And Byrne was waiting for them, a tall, dark shadow in the black depths of the piazza. Graham would have edged away and gone to his own den, but Plume held to

Comments (0)