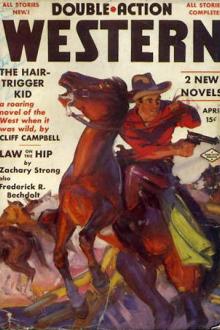

The Hair-Trigger Kid - Max Brand (uplifting novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid - Max Brand (uplifting novels .TXT) 📗». Author Max Brand

most of them ain’t got none at ‘all. And that old Milman, he sure made a

grand mistake, and I’ll tell you why.

“Little Crow, he was a great chief, and all that, and he had cut off

enough hair to plant a forty-acre field, but the trouble was that he

wasn’t the main chief of that tribe, and that he had no more right to

sell off a part of the land than I have to sell Broadway and Beekman

Street. No, sir, he didn’t have no right at all. And before there was a

sale, there should of been a grand palaver, and all the chiefs there, and

specially New Monday, which was really the head of the tribe, though he

hadn’t taken a scalp for thirty years he was that old.

“When we heard that, we went around and we found out that the Injuns

still had a right to this land, if the sale by Little Crow was wrong and

we find out that the real head of the tribe today is Happy Monday—he’s a

descendant of New Monday. So we go to see Happy Monday, and he’s sick in

one eye and can’t see very good out of the other, and we get Happy Monday

to sell us this here bit of land for three hosses and three hogsheads of

alcohol, which is dirt cheap. But it’s hard to educate redskins up to

high prices. And we get that sale made, and we come down here and move

onto the land that’s rightfully ours. And if Milman, he don’t believe

that we got the right, he can go to the law and get licked—or he can try

gunpowder—and get licked.”

Spot Gregory bit his lip.

“That’s a mighty movin’ story,” said he. “Maybe you’ll tell me what you’d

sell out this bit of land for?”

Champ Dixon looked around him with an obvious complacency.

“They’s a thing that you might of noted,” said he. “That we got the water

rights of this here ranch in our pants pockets.”

“I’ve noted that the cows is stickin’ out their tongues and bawlin’ for

somethin’ more than air,” said he.

“Well, sir,” said Champ Dixon, licking his lips, “it occurs to me and

Billy Shay that it would be a dog-gone outright shame to sell this here

crop of water, that never needs to be planted and that comes to hundreds

of millions of tons a year—it would be a dog-gone shame to sell it for

less’n a coupla hundred dollars”

Spot Gregory. looked blandly around him at the flowing thousand stream

and at the running water.

“You want two hundred thousand?” said he.

“That’s the price, old son.”

“And how much you charge for all of the fine sunshine and the air that

the cows will be breathin’?”

“Billy and me is downright generous,” said the other, “and we throw that

in as a kind of bounty to sweeten the deal.”

“Yeah, it sweetens it, all right,” said Spot Gregory. “Now, just

supposin’ that we wanted a time to think this deal over—that Milman

wanted time, I mean?”

“Take all the time that you want,” said the other. “Only I hope that your

cows won’t be dyin’ like flies in the meantime.”

“And suppose that we wanted to water ‘em while we was thinkin’?”

“I never heard of a cow needin’ water to think on,” said Dixon grimly.

“And you can tell Milman that for me, too.”

“I’ll tell him,” agreed the other. “Now, then, suppose that we wanted to

water them cows, how much would you charge a head?”

“We’re reasonable,” said Champ Dixon. “It sure does grieve us a lot to

think of cows goin’ thirsty. So we’re willin’ to let you water them cows

for two dollars a head.”

“Two dollars?” shouted the foreman. “We might as well haul beer up here

and water ‘em with that!”

“Well,” said the other thoughtfully, “I never figgered on that. But maybe

it would do as good!”

“Gregory hastily pulled out his plug of tobacco and bit off a liberal

corner.

“Is that a go?” said he.

“‘Yeah, that’s a go.”

“No changin’?”

“No.”

“Tell me, Champ—ain’t that Two-gun Porter, and Missouri Slim, and the

Haley brothers, over yonder?”

“Yeah, you’re right.”

“And the rest of your bunch match up? Well,” said Gregory, “I got an idea

that more’n money is gonna be paid for this land. And the color of it is

gonna be red.”

He did not pause to say adieu, but turned the head of his horse and rode

away.

When the foreman was over the ridge, he turned loose that stubborn

broncho, and made him run for his life, with a jab of the spurs or a cut

of the quirt every fifty yards or so.

He made that poor mustang hold to the one gait until it had reached the

ranch house, and then Spot Gregory threw the reins and jumped from a

horse that did not need to be tied. It stood like a lamb, while Spot ran

on into the house.

It was just such a house as a thousand other ranchers in the West had

built before Milman, and would build after him. It was a long strung-out

place in the midst of what had once been a flourishing grove, but the

nearest trees had been cut away for firewood, regardless of shady comfort

in the middle of the summer. All the ground around the house was stamped

bare by the horses which were often tied up in great lines to the

hitching racks. Through the naked dust, a dozen or so of chickens

scratched and went about thrusting their heads before them at every step.

A heavy wind of a few years before had threatened to knock down the

kitchen wing like a stack of cards, and this had been secured with a

great pair of plough chains, taken up taut with a tourniquet. This chain

was the only ornament that appeared on that unpainted barn of a house. It

leaned all askew. It was plainly no more than a shelter, with little

pretension of being a comfortable house. Yet the Milman hospitality was

famous for two hundred miles.

Into this house ran Spot, entering through the kitchen door, which he

kicked open in the face of the Chinese cook. The latter sat down

violently upon the floor and the armful of baking tins which he was

carrying went clattering to the farthest corners. He looked surprised,

but not offended. He was prepared for anything up to murder from these

wild white men.

“Where’s the boss?” shouted Spot.

“No savvy,” said the cook, blinking.

“I’m in here, Spot,” said Milman from the dining room.

Gregory strode to the door. He was too excited and angry to remember to

take off his hat. He stood there towering in the doorway, scowling as

though it was Milman whom he hated.

It was still fairly early in the morning, though late for a ranch

breakfast, but Milman had adopted easier ways of living, since his

fortune had become so secure in the past few years. The ranch was a gold

mine, and the vein of it promised to last forever.

Opposite the rancher sat his daughter, and Mrs. Milman who looked small

and frail at the end of the table. She was one of those delicate and

thin-faced women who seem to be half with the angels all the time; as a

matter of fact, she always knew the price of beef on the hoof to an

eighth of a cent.

“What’s loose, Spot?” asked Milman.

“Hell’s loose,” said Gregory shortly. “Plumb hell, is what is loose!”

Then he remembered the ladies and by way of apology, he took off his hat.

“Go on,” said Milman.

Gregory pointed with a long arm.

“Champ Dixon, he’s jumped the water rights. He’s camped with about twenty

men and he’s runnin’ a fence on both sides of Hurry Creek.”

Georgia Milman jumped to her feet.

“The scoundrel!” said she.

Her father pushed back his chair with an exclamation at the same moment,

but Mrs. Milman looked up to the ceiling with narrowed eyes, and did not

stir.

“They’re keeping the cows away from the water?” demanded Milman.

“That’s what they’re doin’.”

“I’ll get—I’ll send to Dry Creek, and we’ll have the law out here to

take their scalps. That murdering Dixon, is it?”

“Champ Dixon.”

“Did you see him?”

“I talked to him.”

“Does he know that we can have the sheriff—”

“He says that it’s all legal. That your title from Little Crow ain’t

worth a scrap and that he’s got the real title, now, from another buck in

the tribe.”

“They’re going to use the law. Is that what you mean?” asked Milman

shortly.

“That’s what they say. Billy Shay is behind the deal. Him and his crooked

lawyers, I suppose.”

“Shay, too!” exclaimed Milman. “I’ll—I’ll—”

He stopped.

Perspiration began to pour down his face, though the morning was cold

enough.

“Oh, Dad,” said Georgia, “what can we do?”

“We gotta pay two dollars a head for water rights,” said the foreman,

writhing in mighty rage at the mere thought.

Milman turned purple, but still his expression was that of a dazed man.

Said Mrs. Milman suddenly: “There’s only one thing to do, my dear.”

“What can we do?” said her husband.

“We can drive them from the water by force.”

“Not that crowd,” declared the foreman. “I know ‘em too dog-gone well. I

saw the face of a lot of ‘em, and I knew ‘em out of the old days. They’re

a hand-picked bunch of yeggs. Every one of them is a gunman with a

record. And there’s Champ Dixon at the head of ‘em! You know Dixon.”

“I know all about Dixon,” said Mrs. Milman. “But—we’ve got to get the

cows to the water. We have neighbors. We’ll have to send to them all. The

Wagners and the Peters and the Birch families will never in the world say

no to us.”

“They’ll never budge agin’ a fellow like Dixon,” prohpesied the foreman.

“They all know his record. We need State troops. Besides, Dixon is

claimin’ the law. The Peters and the rest would ride with us agin’ plain

rustlers, or such. But not agin’ Dixon and the chance of the law,

besides.”

“He’s right,” said Milman, dropping his head a little.

He looked like a beaten man. Silence came into the room like a fifth

person and laid a cold hand on every heart.

Then Mrs. Milman went on in her gentle voice: “The cows will soon be

dying, my dear.”

Her husband looked wildly up at her and then away through the window. At

that very moment a calf began to bawl from the feeding corral where the

weaklings were kept.

“We can run the pump night and day—” he began.

“That well runs dry with very little pumping at this time of year,” said

his wife.

“We could dig—”

“You know how deep we have to dig in order to get water, and through what

rock. The cows will be dead, my dear. Every animal on the place, except

the few that we can water from the mill—and precious few that will be.”

“You’ve heard Spot Gregory talk,” said her husband. “He knows these

people

Comments (0)