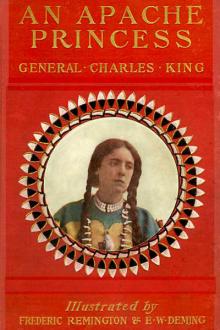

An Apache Princess - Charles King (readict books .TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles King

- Performer: -

Book online «An Apache Princess - Charles King (readict books .TXT) 📗». Author Charles King

At seven o'clock, at last, the post commander came forth from his doorway; saw across the glaring level of the parade the form of Mr. Blakely impatiently pacing the veranda at the adjutant's office, and, instead of going thither, as was his wont, Captain Cutler turned the other way and strode swiftly to the hospital, where Graham met him at the bedside of Trooper patient Patrick Mullins. "How is he?" queried Cutler.

"Sleeping—thank God—and not to be wakened," was the Scotchman's answer. "He had a bad time of it during the fire."

"What am I to tell Blakely?" demanded Cutler, seeking strength for his faltering hand. "You're bound to help me now, Graham."

"Let him go and you may make it worse," said the doctor, with a clamp of his grizzled jaws. "Hold him here and you're sure to."

"Can't you, as post surgeon, tell him he isn't fit to ride?"

"Not when he rides the first half of the night and puts out a nasty fire the last. Can't you, as post commander, tell him you forbid his going till you hear from Byrne and investigate the fire?" If Graham had no patience with a frail woman, he had nothing but contempt for a weak man. "If he's bound to be up and doing something, though," he added, "send him out with a squad of men and orders to hunt for Downs."

Cutler had never even thought of it. Downs was still missing. No one had seen him. His haunts had been searched to no purpose. His horse was still with the herd. One man, the sergeant of the guard, the previous day, had marked the brief farewell between the missing man and the parting maid—had seen the woman's gloved hand stealthily put forth and the little folded packet passed to the soldier's ready palm. What that paper contained no man ventured to conjecture. Cutler and Graham, notified by Sergeant Kenna of what he had seen, puzzled over it in vain. Norah Shaughnessy could perhaps unravel it, thought the doctor, but he did not say.

Cutler came forth from the shaded depths of the broad hallway to face the dazzling glare of the morning sunshine, and the pale, stern, reproachful features of the homeless lieutenant, who simply raised his hand in salute and said: "I've been ready two hours, sir, and the runners are long gone."

"Too long and too far for you to catch them now," said Cutler, catching at another straw. "And there is far more important matter here. Mr. Blakely, I want that man Downs followed, found, and brought back to this post, and you're the only man to do it. Take a dozen troopers, if necessary, and set about it, sir, at once."

A soldier was at the moment hurrying past the front of the hospital, a grimy-looking packet in his hand. Hearing the voice of Captain Cutler, he turned, saw Lieutenant Blakely standing there at attention, saw that, as the captain finished, Blakely still remained a moment as though about to speak—saw that he seemed a trifle dazed or stunned. Cutler marked it, too. "This is imperative and immediate, Mr. Blakely," said he, not unkindly. "Pull yourself together if you are fit to go at all, and lose no more time." With that he started away. Graham had come to the doorway, but Blakely never seemed to see him. Instead he suddenly roused and, turning sharp, sprang down the wooden steps as though to overtake the captain, when the soldier, saluting, held forth the dingy packet.

"It was warped out of all shape, sir," said he. "The blacksmith pried out the lid wid a crowbar. The books are singed and soaked and the packages charred—all but this."

It fell apart as it passed from hand to hand, and a lot of letters, smoke-stained, scorched at the edges, and some of them soaking wet, also two or three carte de visite photographs, were scattered on the sand. Both men bobbed in haste to gather them up, and Graham came hurriedly down to help. As Blakely straightened again he swayed and staggered slightly, and the doctor grasped him by the arm, a sudden clutch that perhaps shook loose some of the recovered papers from the long, slim fingers. At all events, a few went suddenly back to earth, and, as Cutler turned, wondering what was amiss, he saw Blakely, with almost ashen face, supported by the doctor's sturdy arm to a seat on the edge of the piazza; saw, as he quickly retraced his steps, a sweet and smiling woman's face looking up at him out of the trampled sands, and, even as he stooped to recover the pretty photograph, though it looked far younger, fairer, and more winsome than ever he had seen it, Cutler knew the face at once. It was that of Clarice, wife of Major Plume. Whose, then, were those scattered letters?

CHAPTER XIV AUNT JANET BRAVEDightfall of a weary day had come. Camp Sandy, startled from sleep in the dark hour before the dawn, had found topic for much exciting talk, and was getting tired as the twilight waned. No word had come from the party sent in search of Downs, now deemed a deserter. No sign of him had been found about the post. No explanation had occurred to either Cutler or Graham of the parting between Elise and the late "striker." She had never been known to notice or favor him in any way before. Her smiles and coquetries had been lavished on the sergeants. In Downs there was nothing whatsoever to attract her. It was not likely she had given him money, said Cutler, because he was about the post all that day after the Plumes' departure and with never a sign of inebriety. He could not himself buy whisky, but among the ranchmen, packers, and prospectors forever hanging about the post there were plenty ready to play middleman for anyone who could supply the cash, and in this way were the orders of the post commander made sometimes abortive. Downs was gone, that was certain, and the question was, which way?

A sergeant and two men had taken the Prescott road; followed it to Dick's Ranch, in the Cherry Creek Valley, and were assured the missing man had never gone that way. Dick was himself a veteran trooper of the ——th. He had invested his savings in this little estate and settled thereon to grow up with the country—the Stannards' winsome Millie having accepted a life interest in him and his modest property. They knew every man riding that trail, from the daily mail messenger to the semi-occasional courier. Their own regiment had gone, but they had warm interest in its successors. They knew Downs, had known him ever since his younger days when, a trig young Irish-Englishman, some Londoner's discharged valet, he had 'listed in the cavalry, as he expressed it, to reform. A model of temperance, soberness, and chastity was Downs between times, and his gifts as groom of the chambers, as well as groom of the stables, made him, when a model, invaluable to bachelor officers in need of a competent soldier servant. In days just after the great war he had won fame and money as a light rider. It was then that Lieutenant Blake had dubbed him "Epsom" Downs, and well-nigh quarreled with his chum, Lieutenant Ray, over the question of proprietorship when the two were sent to separate stations and Downs was "striking" for both. Downs settled the matter by getting on a seven-days' drunk, squandering both fame and money, and, though forgiven the scriptural seventy times seven (during which term of years his name was changed to Ups and Downs), finally forfeited the favor of both these indulgent masters and became thereafter simply Downs, with no ups of sufficient length to restore the average—much less to redeem him. And yet, when eventually "bobtailed" out of the ——th, he had turned up at the old arsenal recruiting depot at St. Louis, clean-shaven, neat, deft-handed, helpful, to the end that an optimistic troop commander "took him on again," in the belief that a reform had indeed been inaugurated. But, like most good soldiers, the commander referred to knew little of politics or potables, otherwise he would have set less store by the strength of the reform movement and more by that of the potations. Downs went so far on the highroad to heaven this time as to drink nothing until his first payday. Meantime, as his captain's mercury, messenger, and general utility man, moving much in polite society at the arsenal and in town, he was frequently to be seen about Headquarters of the Army, then established by General Sherman as far as possible from Washington and as close to the heart of St. Louis. He learned something of the ins and outs of social life in the gay city, heard much theory and little truth about the time that Lieutenant Blakely, returning suddenly thereto after an absence of two months, during which time frequent letters had passed between him and Clarice Latrobe, found that Major Plume had been her shadow for weeks, her escort to dance after dance, her companion riding, driving, dining day after day. Something of this Blakely had heard in letters from friends. Little or nothing thereof had he heard from her. The public never knew what passed between them (Elise, her maid, was better informed). But Blakely within the day left town again, and within the week there appeared the announcement of her forthcoming marriage, Plume the presumably happy man. Downs got full the first payday after his re-enlistment, as has been said, and drunk, as in duty bound, at the major's "swagger" wedding. It was after this episode he fell utterly from grace and went forth to the frontier irreclaimably "Downs." It was a seven-days' topic of talk at Sandy that Lieutenant Blakely, when acting Indian agent at the reservation, should have accepted the services of this unpromising specimen as "striker." It was a seven-weeks' wonder that Downs kept the pact, and sober as a judge, from the hour he joined the Bugologist to the night that self-contained young officer was sent crashing into his beetle show under the impact of Wren's furious fist. Then came the last pound that broke the back of Downs' wavering resolution, and now had come—what? The sergeant and party rode back from Dick's to tell Captain Cutler the deserter had not taken the Cherry Creek road. Another party just in reported similarly that he had not taken the old, abandoned Grief Hill trail. Still another returned from down-stream ranches to say he could not have taken that route without being seen—and he had not been seen. Ranchman Strom would swear to that because Downs was in his debt for value received in shape of whisky, and Strom was rabid at the idea of his getting away. In fine, as nothing but Downs was missing, it became a matter of speculation along toward tattoo as to whether Downs could have taken anything at all—except possibly his own life.

Cutler was now desirous of questioning Blakely at length, and obtaining his views and theories as to Downs, for Cutler believed that Blakely had certain well-defined views which he was keeping to himself. Between these two, however, had grown an unbridgeable gulf. Dr. Graham had declared at eight o'clock that morning that Mr. Blakely was still so weak that he ought not to go with the searching parties, and on receipt of this dictum Captain Cutler had issued his, to wit, that Blakely

Comments (0)