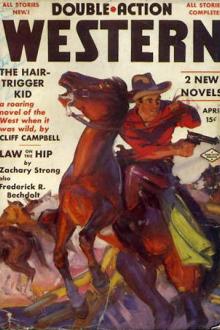

The Hair-Trigger Kid - Max Brand (uplifting novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid - Max Brand (uplifting novels .TXT) 📗». Author Max Brand

these two.

They crossed the bridge over the creek, and there they were seen by the

Warner boys, Paul and Ned, who were fishing off the old ruined landing

which had been built there in the placer days. They both got up and

shouted—regardless of spoiling their fishing prospects for the rest of

the morning. And the Kid turned in his saddle and waved down to them. He

seemed in the highest and most childishly gay spirits, for he made the

Duck Hawk rear so that she stood with her forehoofs resting on the edge

rail which guarded the bridge.

That rail was made of old and time-rotted wood, and the boys held their

breath at this madness of the Kid’s.

Then he whirled the Duck Hawk away, and with a wave of his hand he

disappeared, taking the Langton Trail through the hills.

That trail the Kid followed until after noon. By this time he had climbed

the trail to a height above Dry Creek. He paused at a point where the

trail looped out around the shoulder of a hill, so that he had a clean

view of the path for a distance, going and coming. Moreover, this was a

spot from which he could survey all the country lying back toward Dry

Creek.

He watered the mare at a small creek, which had been one of his reasons

for pausing there, and then he took out a pair of field glasses and first

picked out the northerly hills, the mountains behind them, finally moving

his view down again to Dry Creek, and its shining windows.

He smiled a little when he saw this town, as though of itself it were

something of a joke; then he shifted his view out into the desert,

lingering his eye along the smoky foliage of the draws, and particularly

studying certain dust clouds which, by careful observation, he discovered

were not wind pools, but clouds in slow motion toward Dry Creek.

There were three of these dust clouds. They might be riders, freighters,

almost anything. Carefully estimating distances from point to point, away

out there on the plain, he then timed each of the three dust clouds

across certain stretches.

This had to be inaccurate work, for he could not estimate with any surety

the distances over which the clouds were passing. Yet he knew that those

draws were of about such and such dimensions. He could see, also, that

two of the dust clouds slanted back, and one rose straight up like smoke

from a chimney on a windless day.

He decided that the two slanting clouds were made of horsemen traveling

either at a fast trot or at a gallop. The other dust cloud might be

either quite a large party with their horses at a walk, or, more

probably, it was the sweating team and the rumbling wagon of a freighter.

He put up his glasses and looked more intimately around him. This was the

sort of country that he loved. It was neither the eye-hurting sweep of

the dusty desert, nor the damp gloom of the great forests. It was a

broken sweep of hills, pouring away in a pleasant variety of shapes, and

dressed with patches of high shrubbery and low, while the forest proper

was chiefly confined to the gulleys and the ravines between the hills. In

such a region as this there were a thousand cattle trails weaving through

the maze of hills; there were ten thousand modes of being lost in every

ten miles of travel. It was a place where one needed to know the lay of

the land, and have under one a good horse, with sure footing and a wise

way of taking the ups and downs of a hill journey. The Kid knew this

region well, and he had a wise horse beneath him, that knew how to take

the constantly recurring slopes easily, but at a brisk walk, with a trot

on the summit, and a break into a rolling lope on the downward slope,

moving all the time so softly that there was no danger of battering

shoulders to pieces. Such a horse can cover not twice, but three times as

much ground as an animal not accustomed to the hill country.

But though the Kid knew this country well, he did not know it well enough

to suit him. He never knew any stretch of land well enough. Nothing could

exhaust the patient, the almost passionate interest with which he studied

a landscape in detail. The position of every tree might be worth knowing,

if he had time to get down to the most minor details.

This was almost his profession. The thick roll of his memory could unfold

a scroll which was an endless map of desert, rolling plain, hills,

mountains, wilderness of trees, the courses of rivers, the sites and the

street maps of towns, dottings of ranches and ranch houses, intimate

details of confused trails.

Like a hawk, when he flew into a new region, he first flew high, and from

the summits of the high places he charted the lower regions with an

exquisite precision. The result was that hardly any district could be

strange to him for more than a day, and he had amazed certain ardent

pursuers, over and over again, by his ability to disappear from under

their very noses in a region where they knew, or thought they knew, every

gopher hole.

So the Kid, as the mare grazed eagerly on the fine grass of that

hillside, with the saddle and the bridle both removed, looked carefully

and lovingly over this landscape. There were many creeks where one could

find water, and by those creeks were many dense thickets where man and

horse could hide—particularly a horse taught to lie down in time of

need.

There were high points for spying in this landscape, and there were

crooked and straight ways across the country. That is, there were safe

and leisurely ways, and there were short trails which condensed many

miles of distances into a certain amount of eerie twisting through

ravines and flirting with precipices.

All in all, he felt that this district was made for him. It was “home” to

the Kid.

He had other homes, of course, but they were not quite so satisfactory

for many reasons.

He took out his lunch. It consisted of a ration which an Arab would have

known and appreciated. That is to say, his food was simply dates and old,

stale, tough bread. A morsel of bread, a morsel of date, he chewed them

slowly, with the enjoyment of a hungry man, for already he had ridden far

on this day.

When he had finished his lunch, which was a meager one even for such

simple fare, he drank from the cold water of the creek, and then sat

beside it for a time watching the rippling shadows which flickered over

the sandy bottom, or the flash and paling of the sun upon a quartz

pebble.

It did not take a great deal to interest the Kid. He never had found a

desert so thoroughly devoid of life that it was dull to him. Now, when he

turned from the gazing at the creek, it was to watch the arduous way of

an ant through the grass, lugging with it the head of a beetle twice its

own size and four times its own weight. Ten times the head fell as the

Kid watched. Ten times the ant picked up the burden and pushed ahead,

forcing between narrow blades and climbing then up and then down, like a

monkey struggling with a vast weight through an endless forest.

Eight feet away lay the nest which was the goal! To the ant it was eight

miles of fearful labor.

A light, quick stamp of a hoof made the Kid look up to the Duck Hawk, to

find her standing alert, with tail arching into the wind, and ears

pricked.

The Kid did not delay. He slid bridle and saddle onto her with practiced

speed, and, running hastily down the trail, he came to a rocky stretch,

turned up among the rocks until he came to a thick place of shrubbery and

trees which perfectly concealed him and the mare.

Here he waited, and after a time, sure enough, from down the trail,

traveling south, he heard first the distant ring of an iron-shod hoof,

striking against hard rock, and then the faint snort of a horse. Such

sounds grew nearer and nearer, and around the corner of the mountain rode

a man on a fine gelding of the mustang type, with two lead horses behind

him.

This man carried a short-barreled repeating rifle, or carbine, which he

balanced across the pommel of his saddle. He had two saddle holsters,

from which the butts of revolvers appeared, and a capacious cartridge

belt girded him.

On each of the two led horses there were small packs, but these were so

light that it was obvious that he was using them as extra mounts rather

than as pack animals.

The man himself was what one might call the true Western type; that is to

say, he was tall, rather bony and thin from much exercise, and little fat

from leisure. He had one of those thin, dark faces which one often sees,

with a truly grand forehead, wide and high, and a little puckering at the

corners of his mouth which made him appear to be smiling a great part of

the time. But smiling he was not, as one could guess by a second glance.

This fellow was forty years old, with a back straight as an arrow, a head

carried like a king, and a glance as bright as’ the Kid’s own.

The latter smiled a little and watched with careful attention until the

other reached that point along the trail where the Kid had lunched and

where the mare had grazed.

The instant he came to these signs the rider slumped lower in the saddle,

and tightening the reins, he slipped the carbine under his arm and

whirled his horse about, scanned the rocks and the trees near him with

the eagerness of a hawk and something of a hawk’s hungry and fierce

manner.

He seemed to content himself a little with this first survey, and then

jumped from his saddle to the ground and carefully examined the grass

that had been trampled down by his predecessor. By the movement of it, as

it gradually was rising, he seemed able to tell that his forerunner had

been there a very short time ago indeed. Therefore he straightened again,

and scanned all that was around him suspiciously. Finally he leaped into

the saddle again, and went on a tour of inspection.

What wind was blowing carried straight from the man hunter to the man.

Therefore the Kid carried out an experiment in which he could use the

intelligence and the obedience of the Duck Hawk. He turned the head of

the mare toward a gap in the brush to the rear, and through this, as he

waved his hand, she went at once.

The noise she made was very slight. She walked like a cat, picking out

her way. For horses who have lived a wild life where there is any amount

of shrubbery and trees either learn the ways of silence or die young.

Mountain lions are excellent schoolmasters in all such lessons. So the

Duck Hawk went off with very little noise, and the wind which stirred was

sufficiently strong to cover these slight noises of retreat.

Getting well beyond the patch

Comments (0)