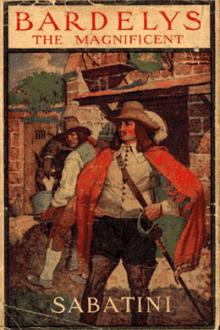

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

a pattern of the class of women amongst whom my youth had been spent,

a class which had done so much towards shattering my faith and

lowering my estimate of her sex. Lavedan had married her and brought

her into Languedoc, and here she spent her years lamenting the scenes

of her youth, and prone, it would seem, to make them matter for

conversation whenever a newcomer chanced to present himself at the

chateau.

Looking from her to her daughter, I thanked Heaven that Roxalanne

was no reproduction of the mother. She had inherited as little of

her character as of her appearance. Both in feature and in soul

Mademoiselle de Lavedan was a copy of that noble, gallant gentleman,

her father.

One other was present at that meal, of whom I shall have more to

say hereafter. This was a young man of good presence, save, perhaps,

a too obtrusive foppishness, whom Monsieur de Lavedan presented to

me as a distant kinsman of theirs, one Chevalier de Saint-Eustache.

He was very tall - of fully my own height - and of an excellent

shape, although extremely young. But his head if anything was too

small for his body, and his good-natured mouth was of a weakness

that was confirmed by the significance of his chin, whilst his eyes

were too closely set to augur frankness.

He was a pleasant fellow, seemingly of that negative pleasantness

that lies in inoffensiveness, but otherwise dull and of an untutored

mind - rustic, as might be expected in one the greater part of whose

life had been spent in his native province, and of a rusticity

rendered all the more flagrant by the very efforts he exerted to

dissemble it.

It was after madame had related that unsavoury anecdote touching

the Cardinal that he turned to ask me whether I was well acquainted

with the Court. I was near to committing the egregious blunder of

laughing in his face, but, recollecting myself betimes, I answered

vaguely that I had some knowledge of it, whereupon he all but caused

me to bound from my chair by asking me had I ever met the Magnificent

Bardelys.

“I - I am acquainted with him,” I answered warily. “Why do you ask?”

“I was reminded of him by the fact that his servants have been here

for two days. You were expecting the Marquis himself, were you not,

Monsieur le Vicomte?”

Lavedan raised his head suddenly, after the manner of a man who has

received an affront.

“I was not, Chevalier,” he answered, with emphasis. “His intendant,

an insolent knave of the name of Rodenard, informed me that this

Bardelys projected visiting me. He has not come, and I devoutly

hope that he may not come. Trouble enough had I to rid myself of

his servants, and but for Monsieur de Lesperon’s well-conceived

suggestion they might still be here.”

“You have never met him, monsieur?” inquired the Chevalier.

“Never,” replied our host in such a way that any but a fool must

have understood that he desired nothing less than such a meeting.

“A delightful fellow,” murmured Saint-Eustache - “a brilliant,

dazzling personality.”

“You - you are acquainted with him?” I asked.

“Acquainted?” echoed that boastful liar. “We were as brothers.”

“How you interest me! And why have you never told us?” quoth madame,

her eyes turned enviously upon the young man - as enviously as were

Lavedan’s turned in disgust. “It is a thousand pities that Monsieur

de Bardelys has altered his plans and is no longer coming to us.

To meet such a man is to breathe again the air of the grand monde.

You remember, Monsieur de Lesperon, that affair with the Duchess de

Bourgogne?” And she smiled wickedly in my direction.

“I have some recollection of it,” I answered coldly. “But I think

that rumour exaggerates. When tongues wag, a little rivulet is

often described as a mountain torrent.”

“You would not say so did you but know what I know,” she informed

me roguishly. “Often, I confess, rumour may swell the importance

of such an affaire, but in this case I do not think that rumour

does it justice.”

I made a deprecatory gesture, and I would have had the subject

changed, but ere I could make an effort to that end, the fool

Saint-Eustache was babbling again.

“You remember the duel that was fought in consequence, Monsieur de

Lesperon?”

“Yes,” I assented wearily.

“And in which a poor young fellow lost his life,” growled the

Vicomte. “It was practically a murder.”

“Nay, monsieur,” I cried, with a sudden heat that set them staring

at me; “there you do him wrong. Monsieur de Bardelys was opposed

to the best blade in France. The man’s reputation as a swordsman

was of such a quality that for a twelvemonth he had been living upon

it, doing all manner of unseemly things immune from punishment by

the fear in which he was universally held. His behaviour in the

unfortunate affair we are discussing was of a particularly shameful

character. Oh, I know the details, messieurs, I can sure you. He

thought to impose his reputation upon Bardelys as he had imposed it

upon a hundred others, but Bardelys was over-tough for his teeth.

He sent that notorious young gentleman a challenge, and on the

following morning he left him dead in the horsemarket behind the

Hotel Vendome. But far from a murder, monsieur, it was an act of

justice, and the most richly earned punishment with which ever man

was visited.”

“Even if so,” cried the Vicomte in some surprise, “why all this heat

to defend a brawler?”

“A brawler?” I repeated after him. “Oh, no. That is a charge his

worst enemies cannot make against Bardelys. He is no brawler. The

duel in question was his first affair of the kind, and it has been

his last, for unto him has clung the reputation that had belonged

until then to La Vertoile, and there is none in France bold enough

to send a challenge to him.” And, seeing what surprise I was

provoking, I thought it well to involve another with me in his

defence. So, turning to the Chevalier, “I am sure,” said I, “that

Monsieur de Saint-Eustache will confirm my words.”

Thereupon, his vanity being all aroused, the Chevalier set himself

to paraphrase all that I had said with a heat that cast mine into

a miserable insignificance.

“At least,” laughed the Vicomte at length, “he lacks not for

champions. For my own part, I am content to pray Heaven that he

come not to Lavedan, as he intended.”

“Mais voyons, Gaston,” the Vicomtesse protested, “why harbour

prejudice? Wait at least until you have seen him, that you may

judge him for yourself.”

“Already have I judged him; I pray that I may never see him.”

“They tell me he is a very handsome man,” said she, appealing to me

for confirmation. Lavedan shot her a sudden glance of alarm, at

which I could have laughed. Hitherto his sole concern had been his

daughter, but it suddenly occurred to him that perhaps not even her

years might set the Vicomtesse in safety from imprudences with this

devourer of hearts, should he still chance to come that way.

“Madame,” I answered, “he is accounted not ill-favored.” And with

a deprecatory smile I added, “I am said somewhat to resemble him.”

“Say you so?” she exclaimed, raising her eyebrows, and looking at

me more closely than hitherto. And then it seemed to me that into

her face crept a shade of disappointment. If this Bardelys were not

more beautiful than I, then he was not nearly so beautiful a man as

she had imagined. She turned to Saint-Eustache.

“It is indeed so, Chevalier?” she inquired. “Do you note the

resemblance?”

“Vanitas, vanitate,” murmured the youth, who had some scraps of

Latin and a taste for airing them. “I can see no likeness - no

trace of one. Monsieur de Lesperon is well enough, I should say.

But Bardelys!” He cast his eyes to the ceiling. “There is but one

Bardelys in France.”

“Enfin,” I laughed,” you are no doubt well qualified to judge,

Chevalier. I had flattered myself that some likeness did exist, but

probably you have seen the Marquis more frequently than have I, and

probably you know him better. Nevertheless, should he come his way,

I will ask you to look at us side by side and be the judge of the

resemblance.”

“Should I happen to be here,” he said, with a sudden constraint not

difficult to understand, “I shall be happy to act as arbiter.”

“Should you happen to be here?” I echoed questioningly. “But surely,

should you hear that Monsieur de Bardelys is about to arrive, you

will postpone any departure you may be on the point of making, so

that you may renew this great friendship that you tell us you do the

Marquis the honour of entertaining for him?”

The Chevalier eyed me with the air of a man looking down from a

great height upon another. The Vicomte smiled quietly to himself as

he combed his fair beard with his forefinger in a meditative fashion,

whilst even Roxalanne - who had sat silently listening to a

conversation that she was at times mercifully spared from following

too minutely - flashed me a humorous glance. To the Vicomtesse alone

who in common with women of her type was of a singular obtuseness -

was the situation without significance.

Saint-Eustache, to defend himself against my delicate imputation,

and to show how well acquainted he was with Bardelys, plunged at

once into a thousand details of that gentleman’s magnificence. He

described his suppers, his retinue, his equipages, his houses, his

chateaux, his favour with the King, his successes with the fair sex,

and I know not what besides - in all of which I confess that even

to me there was a certain degree of novelty. Roxalanne listened

with an air of amusement that showed how well she read him. Later,

when I found myself alone with her by the river, whither we had

gone after the repast and the Chevalier’s reminiscences were at

an end, she reverted to that conversation.

“Is not my cousin a great fanfarron, monsieur,” she asked.

“Surely you know your cousin better than I,” I answered cautiously.

“Why question me upon his character?”

“I was hardly questioning; I was commenting. He spent a fortnight

in Paris once, and he accounts himself, or would have us account

him, intimate with every courtier at the Luxembourg. Oh, he is very

amusing, this good cousin, but tiresome too.” She laughed, and

there was the faintest note of scorn in her amusement. “Now,

touching this Marquis de Bardelys, it is very plain that the

Chevalier boasted when he said that they were as brothers - he and

the Marquis - is it not? He grew ill at ease when you reminded

him of the possibility of the Marquis’s visit to Lavedan.” And she

laughed quaintly to herself. “Do you think that he so much as

knows Bardelys?” she asked me suddenly.

“Not so much as by sight,” I answered. “He is full of information

concerning that unworthy gentleman, but it is only information

that the meanest scullion in Paris might afford you, and just as

inaccurate.”

“Why do you speak of him as unworthy? Are you of the same opinion

as my father?”

“Aye, and with better cause.”

“You know him well?”

“Know him? Pardieu, he is my worst enemy. A worn-out libertine;

a sneering, cynical misogynist; a nauseated reveller; a hateful

egotist. There is no more unworthy person, I’ll swear, in

Comments (0)