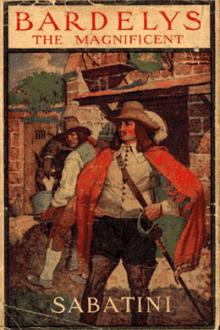

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

“Look in my face, Roxalanne. Can you see nothing there of how I am

torturing myself?”

“Then tell me, monsieur,” she begged, her voice a very caress of

suppliant softness, - “tell me what vexes you and sets a curb upon

your tongue. You exaggerate, I am assured. You could do nothing

dishonourable, nothing vile.”

“Child,” I cried, “I thank God that you are right! I cannot do

what is dishonourable, and I will not, for all that a month ago

I pledged myself to do it!”

A sudden horror, a doubt, a suspicion flashed into her glance.

“You - you do not mean that you are a spy?” she asked; and from my

heart a prayer of thanks went up to Heaven that this at least it

was mine frankly to deny.

“No, no - not that. I am no spy.”

Her face cleared again, and she sighed.

“It is, I think, the only thing I could not forgive. Since it is

not that, will you not tell me what it is?”

For a moment the temptation to confess, to tell her everything, was

again upon me. But the futility of it appalled me.

“Don’t ask me,” I besought her; “you will learn it soon enough.”

For I was confident that once my wager was paid, the news of it and

of the ruin of Bardelys would spread across the face of France like

a ripple over water. Presently—

“Forgive me for having come into your life, Roxalanne!” I implored

her, and then I sighed again. “Helas! Had I but known you earlier!

I did not dream such women lived in this worn-out France.”

“I will not pry, monsieur, since your resolve appears to be so firm.

But if - if after I have heard this thing you speak of,” she said

presently, speaking with averted eyes, “and if, having heard it, I

judge you more mercifully than you judge yourself, and I send for

you, will you - will you come back to Lavedan?”

My heart gave a great bound - a great, a sudden throb of hope. But

as sudden and as great was the rebound into despair.

“You will not send for me, be assured of that,” I said with finality;

and we spoke no more.

I took the oars and plied them vigorously. I was in haste to end

the situation. Tomorrow I must think of my departure, and, as I

rowed, I pondered the words that had passed between us. Not one

word of love had there been, and yet, in the very omission of it,

avowal had lain on either side. A strange wooing had been mine - a

wooing that precluded the possibility of winning, and yet a wooing

that had won. Aye, it had won; but it might not take. I made fine

distinctions and quaint paradoxes as I tugged at my oars, for the

human mind is a curiously complex thing, and with some of us there

is no such spur to humour as the sting of pain.

Roxalanne sat white and very thoughtful, but with veiled eyes, so

that I might guess nothing of what passed within her mind.

At last we reached the chateau, and as I brought the boat to the

terrace steps, it was Saint-Eustache who came forward to offer his

wrist to Mademoiselle.

He noted the pallor of her face, and darted me a quick,

suspicion-laden glance. As we were walking towards the chateau—

“Monsieur de Lesperon,” said he in a curious tone, “do you know that

a rumour of your death is current in the province?”

“I had hoped that such a rumour might get abroad when I disappeared,”

I answered calmly.

“And you have taken no single step to contradict it?”

“Why should I, since in that rumour may be said to lie my safety?”

“Nevertheless, monsieur, voyons. Surely you might at least relieve

the anxieties the affliction, I might almost say - of those who are

mourning you.”

“Ah!” said I. “And who may these be?”

He shrugged his shoulders and pursed his lips in a curiously

deprecatory smile. With a sidelong glance at Mademoiselle—

“Do you need that I name Mademoiselle de Marsac?” he sneered.

I stood still, my wits busily working, my face impassive under his

scrutinizing glance. In a flash it came to me that this must be

the writer of some of the letters Lesperon had given me, the original

of the miniature I carried.

As I was silent, I grew suddenly conscious of another pair of eyes

observing me, Mademoiselle’s. She remembered what I had said, she

may have remembered how I had cried out the wish that I had met her

earlier, and she may not have been slow to find an interpretation

for my words. I could have groaned in my rage at such a

misinterpretation. I could have taken the Chevalier round to the

other side of the chateau and killed him with the greatest relish

in the world. But I restrained myself, I resigned myself to be

misunderstood. What choice had I?

“Monsieur de Saint-Eustache,” said I very coldly, and looking him

straight between his close-set eyes, “I have permitted you many

liberties, but there is one that I cannot permit any one - and, much

as I honour you, I can make no exception in your favour. That is

to interfere in my concerns and presume to dictate to me the manner

in which I shall conduct them. Be good enough to bear that in your

memory.”

In a moment he was all servility. The sneer passed out of his face,

the arrogance out of his demeanour. He became as full of smiles

and capers as the meanest sycophant.

“You will forgive me, monsieur!” he cried, spreading his hands, and

with the humblest smile in the world. “I perceive that I have taken

a great liberty; yet you have misunderstood its purport. I sought

to sound you touching the wisdom of a step upon which I have

ventured.”

“That is, monsieur?” I asked, throwing back my head, with the scent

of danger breast high.

“I took it upon myself to-day to mention the fact that you are alive

and well to one who had a right, I thought, to know of it, and who

is coming hither tomorrow.”

“That was a presumption you may regret,” said I between my teeth.

“To whom do you impart this information?”

“To your friend, Monsieur de Marsac,” he answered, and through his

mask of humility the sneer was again growing apparent. “He will

be here tomorrow,” he repeated.

Marsac was that friend of Lesperon’s to whose warm commendation of

the Gascon rebel I owed the courtesy and kindness that the Vicomte

de Lavedan had meted out to me since my coming.

Is it wonderful that I stood as if frozen, my wits refusing to work

and my countenance wearing, I doubt not, a very stricken look? Here

was one coming to Lavedan who knew Lesperon - one who would unmask me

and say that I was an impostor. What would happen then? A spy they

would of a certainty account me, and that they would make short work

of me I never doubted. But that was something that troubled me less

than the opinion Mademoiselle must form. How would she interpret

what I had said that day? In what light would she view me hereafter?

Such questions sped like swift arrows through my mind, and in their

train came a dull anger with myself that I had not told her

everything that afternoon. It was too late now. The confession

would come no longer of my own free will, as it might have done an

hour ago, but would be forced from me by the circumstances that

impended. Thus it would no longer have any virtue to recommend it

to her mercy.

“The news seems hardly welcome, Monsieur de Lesperon,” said

Roxalanne in a voice that was inscrutable. Her tone stirred me, for

it betokened suspicion already. Something might yet chance to aid

me, and in the mean while I might spoil all did I yield to this

dread of the morrow. By an effort I mastered myself, and in tones

calm and level, that betrayed nothing of the tempest in my soul—

“It is not welcome, mademoiselle,” I answered. “I have excellent

reasons for not desiring to meet Monsieur de Marsac.”

“Excellent, indeed, are they!” lisped Saint-Eustache, with an ugly

droop at the corners of his mouth. “I doubt not you’ll find it

hard to offer a plausible reason for having left him and his sister

without news that you were alive.”

“Monsieur,” said I at random, “why will you drag in his sister’s

name?”

“Why?” he echoed, and he eyed me with undisguised amusement. He

was standing erect, his head thrown back, his right arm outstretched

from the shoulder, and his hand resting lightly upon the gold mount

of his beribboned cane. He let his eyes wander from me to Roxalanne,

then back again to me. At last: “Is it wonderful that I should

drag in the name of your betrothed?” said he. But perhaps you will

deny that Mademoiselle de Marsac is that to you?” he suggested.

And I, forgetting for the moment the part I played and the man whose

identity I had put on, made answer hotly: “I do deny it.”

“Why, then, you lie,” said he, and shrugged hits shoulders with

insolent contempt.

In all my life I do not think it could be said of me that I had ever

given way to rage. Rude, untutored minds may fall a prey to passion,

but a gentleman, I hold, is never angry. Nor was I then, so far as

the outward signs of anger count. I doffed my hat with a sweep to

Roxalanne, who stood by with fear and wonder blending in her glance.

“Mademoiselle, you will forgive that I find it necessary to birch

this babbling schoolboy in your presence.”

Then, with the pleasantest manner in the world, I stepped aside, and

plucked the cane from the Chevalier’s hand before he had so much as

guessed what I was about. I bowed before him with the utmost

politeness, as if craving his leave and tolerance for what I was

about to do, and then, before he had recovered from his astonishment,

I had laid that cane three times in quick succession across his

shoulders. With a cry at once of pain and of mortification, he

sprang back, and his hand dropped to his hilt.

“Monsieur,” Roxalanne cried to him, “do you not see that he is

unarmed?”

But he saw nothing, or, if he saw, thanked Heaven that things were

in such case, and got his sword out. Thereupon Roxalanne would have

stepped between us, but with arm outstretched I restrained her.

“Have no fear, mademoiselle,” said I very quietly; for if the wrist

that had overcome La Vertoile were not with a stick a match for a

couple of such swords as this coxcomb’s, then was I forever shamed.

He bore down upon me furiously, his point coming straight for my

throat. I took the blade on the cane; then, as he disengaged and

came at me lower, I made counter-parry, and pursuing the circle after

I had caught his steel, I carried it out of his hand. It whirled an

instant, a shimmering wheel of light, then it clattered against the

marble balustrade half a dozen yards away. With his sword it seemed

that his courage, too, departed, and he stood at my mercy, a curious

picture of foolishness, surprise, and

Comments (0)