The Mysterious Island - Jules Verne (best fiction books of all time .txt) 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

Book online «The Mysterious Island - Jules Verne (best fiction books of all time .txt) 📗». Author Jules Verne

Meantime, the engineer had sunk into a lethargy, the result of the journey, and his help could not be asked for just then. The supper, therefore, would be very meagre. All the tetras had been eaten, there was no way to cook other birds, and, finally, the couroucous which had been reserved had disappeared. Something, therefore, must be done.

First of all, Cyrus Smith was carried into the main corridor. There they were able to make for him a couch of seaweeds, and, doubtless, the deep sleep in which he was plunged, would strengthen him more than an abundant nourishment.

With night the temperature, which the northwest wind had raised, again became very cold, and, as the sea had washed away the partitions which Pencroff had constructed, draughts of air made the place scarcely habitable. The engineer would therefore have been in a bad plight if his companions had not covered him with clothing which they took from themselves.

The supper this evening consisted of the inevitable lithodomes, an ample supply of which Herbert and Neb had gathered from the beach. To these the lad had added a quantity of edible seaweed which clung to the high rocks and were only washed by the highest tides. These seaweeds, belonging to the family of Fucaceæ, were a species of Sargassum, which, when dry, furnish a gelatinous substance full of nutritive matter, much used by the natives of the Asiatic coast. After having eaten a quantity of lithodomes the reporter and his companions sucked some of the seaweed, which they agreed was excellent.

“Nevertheless,” said the sailor, “it is time for Mr. Smith to help us.”

Meantime the cold became intense, and, unfortunately, they had no means of protecting themselves. The sailor, much worried, tried every possible means of procuring a fire. He had found some dry moss, and by striking two stones together he obtained sparks; but the moss was not sufficiently inflammable to catch fire, nor had the sparks the strength of those struck by a steel. The operation amounted to nothing. Then Pencroff, although he had no confidence in the result, tried rubbing two pieces of dry wood together, after the manner of the savages. It is true that the motion of the man, if it could have been turned into heat, according to the new theory, would have heated the boiler of a steamer. But it resulted in nothing except putting him in a glow, and making the wood hot. After half an hour’s work Pencroff was in a perspiration, and he threw away the wood in disgust.

“When you can make me believe that savages make fire after that fashion,” said he, “it will he hot in winter! I might as well try to light my arms by rubbing them together.”

But the sailor was wrong to deny the feasibility of this method. The savages frequently do light wood in this way. But it requires particular kinds of wood, and, moreover, the “knack,” and Pencroff had not this “knack.”

Pencroff’s ill humor did not last long. The bits of wood which he had thrown away had been picked up by Herbert, who exerted himself to rub them well. The strong sailor could not help laughing at the boy’s weak efforts to accomplish what he had failed in.

“Rub away, my boy; rub hard!” he cried.

“I am rubbing them,” answered Herbert, laughing, “but only to take my turn at getting warm, instead of sitting here shivering; and pretty soon I will be as hot as you are, Pencroff!”

This was the case, and though it was necessary for this night to give up trying to make a fire, Spilett, stretching himself upon the sand in one of the passages, repeated for the twentieth time that Smith could not be baffled by such a trifle. The others followed his example, and Top slept at the feet of his master.

The next day, the 28th of March, when the engineer awoke, about 8 o’clock, he saw his companions beside him watching, and, as on the day before, his first words were,

“Island or continent?”

It was his one thought.

“Well, Mr. Smith,” answered Pencroff, “we don’t know.”

“You haven’t found out yet?”

“But we will,” affirmed Pencroff, “when you are able to guide us in this country.”

“I believe that I am able to do that now,” answered the engineer, who, without much effort, rose up and stood erect.

“That is good,” exclaimed the sailor.

“I am dying of hunger,” responded Smith. “Give me some food, my friend, and I will feel better. You’ve fire, haven’t you?”

This question met with no immediate answer. But after some moments the sailor said:—

“No, sir, we have no fire; at least, not now.”

And be related what had happened the day before. He amused the engineer by recounting the history of their solitary match, and their fruitless efforts to procure fire like the savages.

“We will think about it,” answered the engineer, “and if we cannot find something like tinder—”

“Well,” asked the sailor.

“Well, we will make matches!”

“Friction matches?”

“Friction matches!”

“It’s no more difficult than that,” cried the reporter, slapping the sailor on the shoulder.

The latter did not see that it would be easy, but he said nothing, and all went out of doors. The day was beautiful. A bright sun was rising above the sea horizon, its rays sparkling and glistening on the granite wall. After having cast a quick look about him, the engineer seated himself upon a rock. Herbert offered him some handfuls of mussels and seaweed, saying:—

“It is all that we have, Mr. Smith.”

“Thank you, my boy,” answered he, “it is enough—for this morning, at least.”

And he ate with appetite this scanty meal, washing it down with water brought from the river in a large shell.

His companions looked on without speaking. Then, after having satisfied himself, he crossed his arms and said:—

“Then, my friends, you do not yet know whether we have been thrown upon an island or a continent?”

“No sir,” answered Herbert.

“We will find out to-morrow,” said the engineer. “Until then there is nothing to do.”

“There is one thing,” suggested Pencroff.

“What is that?”

“Some fire,” replied the sailor, who thought of nothing else.

“We will have it, Pencroff,” said Smith. “But when you were carrying me here yesterday, did not I see a mountain rising in the west?”

“Yes,” saidSpilett, “quite a high one.”

“All right,” exclaimed the engineer. “Tomorrow we will climb to its summit and determine whether this is an island or a continent; until then I repeat there is nothing to do.”

“But there is; we want fire!” cried the obstinate sailor again.

“Have a little patience, Pencroff, and we will have the fire,” said Spilett.

The other looked at the reporter as much as to say, “If there was only you to make it we would never taste roast meat.” But he kept silent.

Smith had not spoken. He seemed little concerned about this question of fire. For some moments he remained absorbed in his own thoughts. Then he spoke as follows:—

“My friends, our situation is, doubtless, deplorable, nevertheless it is very simple. Either we are upon a continent, and, in that case, at the expense of greater or less fatigue, we will reach some inhabited place, or else we are on an island. In the latter case, it is one of two things; if the island is inhabited, we will get out of our difficulty by the help of the inhabitants; if it is deserted, we will get out of it by ourselves.”

“Nothing could be plainer than that,” said Pencroff.

“But,” asked Spilett, “whether it is a continent or an island, whereabouts do you think this storm has thrown us, Cyrus?”

“In truth, I cannot say,” replied the engineer, “but the probability is that we are somewhere in the Pacific. When we left Richmond the wind was northeast, and its very violence proves that its direction did not vary much. Supposing it unchanged, we crossed North and South Carolina, Georgia, the Gulf of Mexico, and the narrow part of Mexico, and a portion of the Pacific Ocean. I do not estimate the distance traversed by the balloon at less than 6,000 or 7,000 miles, and even if the wind had varied a half a quarter it would have carried us either to the Marquesas Islands or to the Low Archipelago; or, if it was stronger than I suppose, as far as New Zealand. If this last hypothesis is correct, our return home will be easy. English or Maoris, we shall always find somebody with whom to speak. If, on the other hand, this coast belongs to some barren island in the Micronesian Archipelago, perhaps we can reconnoitre it from the summit of this mountain, and then we will consider how to establish ourselves here as if we were never going to leave it.”

“Never?” cried the reporter. “Do you say never, my dear Cyrus?”

“It is better to put things in their worst light at first,” answered the engineer; “and to reserve those which are better, as a surprise.”

“Well said,” replied Pencroff. “And we hope that this island, if it is an island, will not be situated just outside of the route of ships; for that would, indeed, be unlucky.”

“We will know how to act after having first ascended the mountain,” answered Smith.

“But will you be able, Mr. Smith, to make the climb tomorrow?” asked Herbert.

“I hope so,” answered the engineer, “if Pencroff and you, my boy, show yourselves to be good and ready hunters.”

“Mr. Smith,” said the sailor, “since you are speaking of game, if when I come back I am as sure of getting it roasted as I am of bringing it—”

“Bring it, nevertheless,” interrupted Smith.

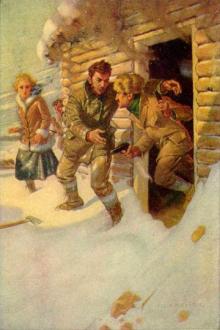

It was now agreed that the engineer and the reporter should spend the day at the Chimneys, in order to examine the shore and the plateau, while Neb, Herbert, and the sailor were to return to the forest, renew the supply of wood, and lay hands on every bird and beast that should cross their path. So, at 6 o’clock, the party left, Herbert confident. Neb happy, and Pencroff muttering to himself:—

“If, when I get back I find a fire in the house, it will have been the lightning that lit it!”

The three climbed the bank, and having reached the turn in the river, the sailor stopped and said to his companions:—

“Shall we begin as hunters or wood-choppers?”

“Hunters,” answered Herbert. “See Top, who is already at it.”

“Let us hunt, then,” replied the sailor, “and on our return here we will lay in our stock of wood.”

This said, the party made three clubs for themselves, and followed Top, who was jumping about in the high grass.

This time, the hunters, instead of following the course of the stream, struck at once into the depths of the forests. The trees were for the most part of the pine family. And in certain places, where they stood in small groups, they were of such a size as to indicate that this country was in a higher latitude than the engineer supposed. Some openings, bristling with stumps decayed by the weather, were covered with dead timber which formed an inexhaustible reserve of firewood. Then, the opening passed, the underwood became so thick as to be nearly impenetrable.

To guide oneself among these great trees without any beaten path was very difficult. So the sailer from time to time blazed the route by breaking branches in a manner easily recognizable. But perhaps they would have done better to have followed the water course, as in the first instance, as, after an hour’s march, no game had been taken. Top, running under the low boughs,

Comments (0)