The Mysterious Island - Jules Verne (best fiction books of all time .txt) 📗

- Author: Jules Verne

Book online «The Mysterious Island - Jules Verne (best fiction books of all time .txt) 📗». Author Jules Verne

“Well, Pencroff,” said Neb sarcastically, “if this is all the game you promised to carry back to my master it won’t take much fire to roast it!”

“Wait a bit, Neb,” answered the sailor; “it won’t be game that will be wanting on our return.”

“Don’t you believe in Mr. Smith?”

“Yes.”

“But you don’t believe be will make a fire?”

“I will believe that when the wood is blazing in the fire-place.”

“It will blaze, then, for my master has said so!”

“Well, we’ll see!”

Meanwhile the sun had not yet risen to its highest point above the horizon. The exploration went on and was signalized by Herbert’s discovery of a tree bearing edible fruit. It was the pistachio pine, which bears an excellent nut, much liked in the temperate regions of America and Europe. These nuts were perfectly ripe, and Herbert showed them to his companions, who feasted on them.

“Well,” said Pencroff, “seaweed for bread, raw mussels for meat, and nuts for dessert, that’s the sort of dinner for men who haven’t a match in their pocket!”

“It’s not worth while complaining,” replied Herbert.

“I don’t complain, my boy. I simply repeat that the meat is a little too scant in this sort of meal.”

“Top has seen something!” cried Neb, running toward a thicket into which the dog had disappeared barking. With the dog’s barks were mingled singular gruntings. The sailor and Herbert had followed the negro. If it was game, this was not the time to discuss how to cook it, but rather how to secure it.

The hunters, on entering the brush, saw Top struggling with an animal which he held by the ear. This quadruped was a species of pig, about two feet and a half long, of a brownish black color, somewhat lighter under the belly, having harsh and somewhat scanty hair, and its toes at this time strongly grasping the soil seemed joined together by membranes.

Herbert thought that he recognized in this animal a cabiai, or water-hog, one of the largest specimens of the order of rodents. The water-hog did not fight the dog. Its great eyes, deep sank in thick layers of fat, rolled stupidly from side to side. And Neb, grasping his club firmly, was about to knock the beast down, when the latter tore loose from Top, leaving a piece of his ear in the dog’s mouth, and uttering a vigorous grunt, rushed against and overset Herbert and disappeared in the wood.

“The beggar!” cried Pencroff, as they all three darted after the hog. But just as they had come up to it again, the water-hog disappeared under the surface of a large pond, overshadowed by tall, ancient pines.

The three companions stopped, motionless. Top had plunged into the water, but the cabiai, hidden at the bottom of the pond, did not appear.

“Wait,”, said the boy, “he will have to come to the surface to breathe.”

“Won’t he drown?” asked Neb.

“No,” answered Herbert, “since he is fin-toed and almost amphibious. But watch for him.”

Top remained in the water, and Pencroff and his companions took stations upon the bank, to cut off the animal’s retreat, while the dog swam to and fro looking for him.

Herbert was not mistaken. In a few minutes the animal came again to the surface. Top was upon him at once, keeping him from diving again, and a moment later, the cabiai, dragged to the shore, was struck down by a blow from Neb’s club.

“Hurrah!” cried Pencroff with all his heart. “Nothing but a clear fire, and this gnawer shall be gnawed to the bone.”

Pencroff lifted the carcase to his shoulder, and judging by the sun that it must be near 2 o’clock, he gave the signal to return.

Top’s instinct was useful to the hunters, as, thanks to that intelligent animal, they were enabled to return upon their steps. In half an hour they had reached the bend of the river. There, as before, Pencroff quickly constructed a raft, although, lacking fire, this seemed to him a useless job, and, with the raft keeping the current, they returned towards the Chimneys. But the sailor had not gone fifty paces when he stopped and gave utterance anew to a tremendous hurrah, and extending his hand towards the angle of the cliff—

“Herbert! Neb! See!” he cried.

Smoke was escaping and curling above the rocks!

CHAPTER X.

THE ENGINEER’S INVENTION—ISLAND OR CONTINENT?—DEPARTURE FOR THE MOUNTAIN—THE FOREST—VOLCANIC SOIL—THE TRAGOPANS—THE MOUFFLONS —THE FIRST PLATEAU—ENCAMPING FOR THE NIGHT—THE SUMMIT OF THE CONE

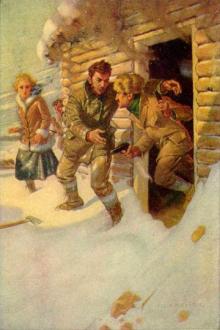

A few minutes afterwards, the three hunters were seated before a sparkling fire. Beside them sat Cyrus Smith and the reporter. Pencroff looked from one to the other without saying a word, his cabiai in his hand.

“Yes, my good fellow,” said the reporter, “a fire, a real fire, that will roast your game to a turn.”

“But who lighted it?” said the sailor.

“The sun.”

The sailor could not believe his eyes, and was too stupefied to question the engineer.

“Had you a burning-glass, sir?” asked Herbert of Cyrus Smith.

“No, my boy,” said he, “but I made one.”

And he showed his extemporized lens. It was simply the two glasses, from his own watch and the reporter’s, which he had taken out, filled with water, and stuck together at the edges with a little clay. Thus he had made a veritable burning-glass, and by concentrating the solar rays on some dry moss had set it on fire.

The sailor examined the lens; then he looked at the engineer without saying a word, but his face spoke for him. If Smith was not a magician to him, he was certainly more than a man. At last his speech returned, and he said:—

“Put that down, Mr. Spilett, put that down in your book!”

“I have it down,” said the reporter.

Then, with the help of Neb, the sailor arranged the spit, and dressed the cabiai for roasting, like a sucking pig, before the sparkling fire, by whose warmth, and by the restoration of the partitions, the Chimneys had been rendered habitable.

The engineer and his companion had made good use of their day. Smith had almost entirely recovered his strength, which he had tested by climbing the plateau above. From thence his eye, accustomed to measure heights and distances, had attentively examined the cone whose summit he proposed to reach on the morrow. The mountain, situated about six miles to the northwest, seemed to him to reach about 3,500 feet above the level of the sea, so that an observer posted at its summit, could command a horizon of fifty miles at least. He hoped, therefore, for an easy solution of the urgent question, “Island or continent?”

They had a pleasant supper, and the meat of the cabiai was proclaimed excellent; the sargassum and pistachio-nuts completed the repast. But the engineer said little; he was planning for the next day. Once or twice Pencroff talked of some project for the future, but Smith shook his head.

“To-morrow,” he said, “we will know how we are situated, and we can act accordingly.”

After supper, more armfuls of wood were thrown on the fire, and the party lay down to sleep. The morning found them fresh and eager for the expedition which was to settle their fate.

Everything was ready. Enough was left of the cabiai for twenty-four hours’ provisions, and they hoped to replenish their stock on the way. They charred a little linen for tinder, as the watch glasses had been replaced, and flint abounded in this volcanic region.

At half-past 7 they left the Chimneys, each with a stout cudgel. By Pencroff’s advice, they took the route of the previous day, which was the shortest way to the mountain. They turned the southern angle, and followed the left bank of the river, leaving it where it bent to the southwest. They took the beaten path under the evergreens, and soon reached the northern border of the forest. The soil, flat and swampy, then dry and sandy, rose by a gradual slope towards the interior. Among the trees appeared a few shy animals, which rapidly took flight before Top. The engineer called his dog back; later, perhaps, they might hunt, but now nothing could distract him from his great object. He observed neither the character of the ground nor its products; he was going straight for the top of the mountain.

At 10 o’clock they were clear of the forest, and they halted for a while to observe the country. The mountain was composed of two cones. The first was truncated about 2,500 feet up, and supported by fantastic spurs, branching out like the talons of an immense claw, laid upon the ground. Between these spurs were narrow valleys, thick set with trees, whose topmost foliage was level with the flat summit of the first cone. On the northeast side of the mountain, vegetation was more scanty, and the ground was seamed here and there, apparently with currents of lava.

On the first cone lay a second, slightly rounded towards the summit. It lay somewhat across the other, like a huge hat cocked over the ear. The surface seemed utterly bare, with reddish rocks often protruding. The object of the expedition was to reach the top of this cone, and their best way was along the edge of the spurs.

“We are in a volcanic country,” said Cyrus Smith, as they began to climb, little by little, up the side of the spurs, whose winding summit would most readily bring them out upon the lower plateau. The ground was strewn with traces of igneous convulsion. Here and there lay blocks, debris of basalt, pumice-stone, and obsidian. In isolated clumps rose some few of those conifers, which, some hundreds of feet lower, in the narrow gorges, formed a gigantic thicket, impenetrable to the sun. As they climbed these lower slopes, Herbert called attention to the recent marks of huge paws and hoofs on the ground.

“These brutes will make a fight for their territory,” said Pencroff.

“Oh well,” said the reporter, who had hunted tigers in India and lions in Africa, “we shall contrive to get rid of them. In the meanwhile, we must be on our guard.”

While talking they were gradually ascending. The way was lengthened by detours around the obstacles which could not be directly surmounted. Sometimes, too, deep crevasses yawned across the ascent, and compelled them to return upon their track for a long distance, before they could find an available pathway. At noon, when the little company halted to dine at the foot of a great clump of firs, at whose foot babbled a tiny brook, they were still half way from the first plateau, and could hardly reach it before nightfall. From this point the sea stretched broad beneath their feet; but on the right their vision was arrested by the sharp promontory of the southeast, which left them in doubt whether there was land beyond. On the left they could see directly north for several miles; but the northwest was concealed from them by the crest of a fantastic spur, which formed a massive abutment to the central cone. They could, therefore, make no approach as yet to the solving of the great question.

At 1 o’clock, the ascent was again begun. The easiest route slanted upwards towards the southwest, through the thick copse. There, under the trees, were flying about a number of gallinaceæ of the pheasant family. These were “tragopans,” adorned with a sort of fleshy wattles hanging over their necks and with two little cylindrical horns behind their eyes. Of these birds, which were about the size of a hen, the female was invariably brown, while the male was resplendent in a coat of red, with little spots of white. With a well-aimed stone Spilett killed one of the tragopans, which the hungry Pencroff looked at with longing eyes.

Leaving the copse, the climbers, by mounting on each other’s shoulders, ascended for a hundred feet up a

Comments (0)