Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

- Performer: -

Book online «Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Bracebridge Hemyng

But rapid as was the action, Nero saw an opportunity in it whereof he took advantage, for he pounced upon the well-bitten tart, and bore it away in triumph.

This episode, however, was soon forgotten, and Mole began to relate adventures of himself which would have done credit to Baron Munchausen, while Figgins, not to be outdone, told wonderful stories of high life in which he had been personally engaged.

CHAPTER LXXIII.

OF THE DEADLY QUARREL AND MORTAL COMBAT BETWEEN MOLE AND FIGGINS.

"One day," began Mr. Figgins, after a pause, "I was driving along Belgravia Crescent with Lord—bless me! which of 'em was it?"

"Perhaps it was Lord Elpus," suggested Harkaway.

"Or Lord Nozoo?" said Girdwood.

"Are you sure he was a lord at all, Mr. Figgins?" asked Mole, dubiously.

"Mr. Mole," said the orphan, indignantly; "do you doubt my veracity?"

"Not a bit," answered the schoolmaster, "but I doubt the voracity of your hearers being sufficient for them to swallow all you are telling us."

"Well, gentlemen," pursued Figgins, turning from Mole in disgust, "this Lord Whatshisname used to have behind his carriage about the nicest little tiger that ever was seen——"

"Nothing like the tiger I saw in Bengal one day, I'm sure," broke in Mr. Mole, in a loud and positive tone. "Come, Figgins, I'll bet you ten to one on it."

The orphan rose to his feet in great indignation.

"Isaac Mole, Esq., I have borne patiently with injuries almost too great for mortal man throughout this day. I consider myself insulted by you, and I will have satisfaction."

"Well, old boy, if you just mention what will satisfy you, I'll see," said Mole.

"Nothing short of a full and complete apology."

"You don't get that out of me," the schoolmaster scornfully retorted. "Preposterous. What I, Isaac Mole, who took the degree of B. A. at the almost infantine age of thirty-four, to apologise to one who is——"

"Who is what, sir?" demanded Figgins.

"Never mind. I don't want to use unbecoming expressions," said Mole. "You wouldn't like to hear what I was going to say."

The orphan was so angry at this that, unheeding what he was doing, he drank off nearly a tumblerful of strong sherry at once.

This, coming on the top of other libations, made the whole scene dance before his bewildered eyes.

He began to see two Moles, and shook his fist, as he thought, upon both of them at once.

"I d—don't care for either of you," he exclaimed, fiercely.

"Either of us? For me, I suppose you mean?" said the tutor.

"Which are you?" asked Figgins.

"Which are who?" retorted Mole.

"Why, there are two of you, and I wa—want to know which is the right one," said Figgins.

"I'm the right one. I always am right," said Mole, aggressively. "You don't dare to imply I'm wrong, do you?"

"Won't say what I imply," answered Figgins, with dignity; "but I know you to be only a——"

"Stop, stop, gentlemen," cried Jack. "Let not discord interrupt the harmony of the festive occasion. Mr. Mole, please tone down the violence of your language. Mr. Figgins, calm your agitation, and give us a song."

"A song?" interrupted Mr. Mole, taking the request to himself. "Oh, with pleasure."

And he struck up one of his favourite bacchanalian chants—

"Jolly nose, Jolly nose, Jolly nose!

The bright rubies that garnish thy tip

Are all sprung from the mines of Canary,

Are all sprung——"

"There's no doubt upon their being all sprung anyhow," whispered Harkaway to Girdwood. "Stop, stop, Mr. Mole," he cried at this juncture. "It was Mr. Figgins, not you, that we called upon for a song."

"Was it?" said the schoolmaster. "Very good; beg pardon. Only thought you'd prefer somebody who could sing. Figgins can't."

Figgins again looked at Mole, as if he were about to fly at him.

But the cry of "A song, a song by Mr. Figgins!" drowned his remonstrances.

"Really do'no what to sing, ladies and gen'l'men," protested Figgins. "Stop a minute. I used to know 'My Harp and Flute.'"

"You mean 'My Heart and Lute,' I suppose?" said Jack.

"Yes, that's it. And I should remember the air, if I hadn't forgotten the words. Let's see. Stop a minute, head's rather queer. Try the water cure."

Whereupon Mr. Figgins staggered to the adjacent brook, and, kneeling down, fairly dipped his head into it.

After having wiped himself with a dinner napkin he rejoined the party, very much refreshed.

"Tell you what, friends, I'll give you a solo on the flute," he said. "Something lively; 'Dead March in Saul' with variations."

And without mere ado, he took up his favourite instrument, and prepared to astonish the company.

If Mr. Figgins did not succeed in astonishing the company, he at least considerably astonished himself, for when he placed the flute to his lips and gave a vigorous preliminary blow, not only did he fail to elicit any musical sound, but he smothered and half-blinded himself with a dense cloud of flour, with which the tube had been entirely filled.

Bogey and Tinker, as usual, had been the real authors of this new atrocity, but Figgins felt convinced that the guilt lay at the door of Mole, on whom he turned for vengeance.

"Villain!" he cried, "this is another of your tricks; it's the last straw. I'll bear it no longer; take that."

As Mr. Figgins spoke, he struck the venerable Mole a sounding whack over the bald part of the cranium with the instrument of harmony.

Mole sprang upon his legs with astonishing alacrity, and, seizing Figgins by the throat, commenced shaking him.

A ferocious struggle ensued, among the remonstrances of the spectators, but, before they could interfere, it ended by both combatants coming down heavily and at their full length on the temporary dinner-table, and thereby breaking not a few plates, bottles, and glasses.

Helped to rise and seated on separate camp-stools, some distance apart, the two former friends, but now mortal foes, as soon as they could get their breath, sat fiercely shaking fists and hurling strong adjectives at each other.

"I'll have it out of you, you old villain!" cried Mole.

"And I'll have it out of you, you old rascal!" shrieked Figgins.

"We'll both have it out," added the tutor, "and the sooner the better. Name your place and your weapons."

"Here," answered Figgins, pointing to an open space before him, "and my weapon is the sword."

"And mine's the pistol," said Mole. "I'll fight with that, and you with your sword."

"Agreed," said the excited Figgins, quite forgetting the impracticability of such an arrangement and the disadvantages it would give him.

Figgins had a battered sabre of the light curved, Turkish make, and Mole rejoiced in the possession of a very old-fashioned pistol.

Mole gave the latter to Girdwood, who volunteered to be his second, and who took care to put nothing in more dangerous than gunpowder.

"Now we're about to see a duel upon a quite original principle," cried Jack to his friends. "I don't think either of them can hurt the other much. I'll be your second, Figgins, my boy."

"All right. I take up my position here," cried the orphan, stationing himself under a tree near the brook.

"I shall stand here," said Mole, stopping at about half a dozen paces from him.

The orphan looked as though he intended to bolt behind the tree if Mole fired.

"Well, Master Harry, don't be in a hurry," said Figgins. "I am not quite ready, are you, Mr. Mole?"

"Oh yes," said Mole, "I am ready."

He fully intended to blow the orphan's head off the first fire.

"I'll give the signal to fire," said Harry. "Now, are you ready; one, two, three!"

Mole's pistol-shot reverberated through the copse, but, as, a matter of course, it did not the slightest harm to Figgins, who, however, thought he heard it strike against the sabre which he held in a position of guard.

It now began, for the first time, to strike the orphan that this novel mode of fighting was very awkward for himself, for how was he to get at his enemy?

At first he poised his sword as if about to fling it at him, then moved by a sudden impulse he rushed forward, with a cry of vengeance, and began attacking Mole furiously with some heavy cutting blows.

Mole, as his only resource, dodged about and caught some of these blows upon his pistol, but judging this risky work, he took up his stick and used it in desperate self-defence; thus dodging and parrying, he retreated while Figgins advanced.

Once Mole managed to get what an Irishman would call "a fair offer" at Figgins' skull, which accordingly resounded with the blow of his weapon.

Half stunned, the orphan plunged madly forward and took a far-reaching aim at the old tutor.

He, in his turn, dodged again, but his wooden legs not being so nimble as real ones, he stumbled over some tall, thick grass, and fell backwards into the stream.

Jack, thinking matters had gone far enough, caught the orphan's foot in a rope, and bent him so far forward that he overbalanced himself and fell on top of Mole, and both tumbled into the water together.

The alarm was given, and they were both drawn out, "wet as drowned rats," but not quite so far gone.

They were, however, entirely sobered by their immersion.

A small glass of brandy, however, was administered to each, to prevent them catching cold, and some of their garments were taken off to dry in the sun.

Mole, the tutor, and Figgins, the orphan, wearied out with their exertions, soon fell fast asleep.

CHAPTER LXXIV.

A TREMENDOUS RISE FOR MR. MOLE.

The quarrel between the two had been so far made up, that when they awoke from their siesta, and the fumes of the alcohol had subsided, neither of them seemed to remember any thing about the matter.

The party got safely home without encountering either robbers, snakes, wolves, thunderstorms, or any other dangerous being or foes whatever.

The next day, however, commenced for Mr. Mole an adventure which at the outset promised to form an exciting page in his life.

He was walking through the streets and bazaars of the town, Jack on one side of him, Harry on the other, though the reader, at first glance, would probably not have recognised any of them.

Harkaway and Girdwood presented the appearance of Ottoman civilians belonging to the "Young Turkey" party, whilst the venerable tutor stalked along in full fig as a magnificent robed and turbaned Turk of the old school.

It had become quite a mania with Isaac to turn himself as far as he possibly could into a Moslem.

He had taken quite naturally to the Turkish tobacco, and the national mode of smoking it through a chibouque, or water-pipe.

But in outward appearance Mr. Mole had certainly succeeded in turning Turk, more especially as he had fixed on a large false grey beard, which matched beautifully with his green and gold turban.

He had again mounted his cork legs, and encased his cork feet with splendid-fitting patent leather boots, and Mole felt happy.

"They take me for a pasha of three tails, don't you think so?" he delightedly asked his companions.

"Half a dozen tails at least, I should say," returned Jack, "and of course they take us for a couple of your confidential attendants."

"In that case, I must walk before you, and adopt a proud demeanour, to show my superiority," said Mole.

So whilst Jack and Harry dropped humbly in the rear, he strode forward with a haughty stiffness of dignity, which his two cork legs rather enhanced than otherwise.

"Holloa!" exclaimed Harry, suddenly; "who's this black chap coming up to us, bowing and scraping like a mandarin?"

He alluded to a tall dark man, apparently of the Arab race, but dressed in the full costume of a Turkish officer, who, dismounting his horse, approached Mole with the most elaborate Oriental obeisances, and held out to him a folded parchment.

Mole took the document with a stiff bow, opened it and found it to be a missive in Turkish, which, notwithstanding his studies in that direction, he could not for the world make out.

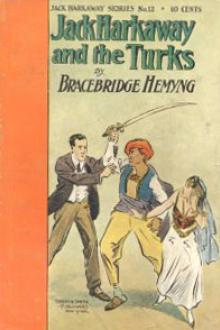

"Mole took the document, and opened it."--Tinker. Vol.II.

"mole took the document, and opened it."—Tinker.

Comments (0)