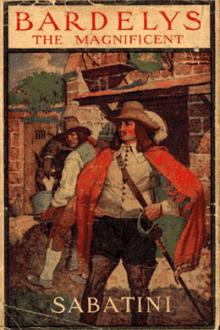

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

the best class in France, and having no more than the vices of my

order. As a monster of profligacy might she behold me, and that

—ah, Dieu! - I could not endure that she should do whilst I

was by.

It may be - indeed, now, as I look back, I know that I exaggerated

my case. I imagined she would see it as I saw it then. For would

you credit it? With this great love that was now come to me, it

seemed the ideals of my boyhood were returned, and I abhorred the

man that I had been. The life I had led now filled me with disgust

and loathing; the notions I had formed seemed to me now all vicious

and distorted, my cynicism shallow and unjust.

“Monsieur de Lesperon,” she called softly to me, noting my silence.

I turned to her. I set my hand lightly upon her arm; I let my gaze

encounter the upward glance of her eyes - blue as forget-me-nots.

“You suffer!” she murmured, with sweet compassion.

“Worse, Roxalanne! I have sown in your heart too the seed of

suffering. Oh, I am too unworthy!” I cried out; “and when you come

to discover how unworthy it will hurt you; it will sting your pride

to think how kind you were to me.” She smiled incredulously, in

denial of my words. “No, child; I cannot tell you.”

She sighed, and then before more could be said there was a sound

at the door, and we started away from each other. The Vicomte

entered, and my last chance of confessing, of perhaps averting

much of what followed, was lost to me.

THE PORTRAIT

Into the mind of every thoughtful man must come at times with

bitterness the reflection of how utterly we are at the mercy of

Fate, the victims of her every whim and caprice. We may set out

with the loftiest, the sternest resolutions to steer our lives

along a well-considered course, yet the slightest of fortuitous

circumstances will suffice to force us into a direction that we had

no thought of taking.

Now, had it pleased Monsieur de Marsac to have come to Lavedan at

any reasonable hour of the day, I should have been already upon

the road to Paris, intent to own defeat and pay my wager. A night

of thought, besides strengthening my determination to follow such a

course, had brought the reflection that I might thereafter return

to Roxalanne, a poor man, it is true, but one at least whose

intentions might not be misconstrued.

And so, when at last I sank into sleep, my mind was happier than

it had been for many days. Of Roxalanne’s love I was assured, and

it seemed that I might win her, after all, once I removed the

barrier of shame that now deterred me. It may be that those

thoughts kept me awake until a late hour, and that to this I owe

it that when on the morrow I awakened the morning was well advanced.

The sun was flooding my chamber, and at my bedside stood Anatole.

“What’s o’clock?” I inquired, sitting bolt upright.

“Past ten,” said he, with stern disapproval.

“And you have let me sleep?” I cried.

“We do little else at Lavedan even when we are awake,” he grumbled.

“There was no reason why monsieur should rise.” Then, holding out

a paper, “Monsieur Stanislas de Marsac was here betimes this morning

with Mademoiselle his sister. He left this letter for you, monsieur.”

Amaze and apprehension were quickly followed by relief, since

Anatole’s words suggested that Marsac had not remained. I took the

letter, nevertheless, with some misgivings, and whilst I turned it

over in my hands I questioned the old servant.

“He stayed an hour at the chateau, monsieur,” Anatole informed me.

“Monsieur le Vicomte would have had you roused, but he would not

hear of it. ‘If what Monsieur de Saint-Eustache has told me touching

your guest should prove to be true,’ said he, ‘I would prefer not

to meet him under your roof, monsieur.’ ‘Monsieur de Saint-Eustache,’

my master replied, ‘is not a person whose word should have weight

with any man of honour.’ But in spite of that, Monsieur de Marsac

held to his resolve, and although he would offer no explanation in

answer to my master’s many questions, you were not aroused.

“At the end of a half-hour his sister entered with Mademoiselle.

They had been walking together on the terrace, and Mademoiselle de

Marsac appeared very angry. ‘Affairs are exactly as Monsieur de

Saint-Eustache has represented them,’ said she to her brother. At

that he swore a most villainous oath, and called for writing

materials. At the moment of his departure he desired me to deliver

this letter to you, and then rode away in a fury, and, seemingly,

not on the best of terms with Monsieur le Vicomte.”

“And his sister?” I asked quickly.

“She went with him. A fine pair, as I live!” he added, casting

his eyes to the ceiling.

At least I could breathe freely. They were gone, and whatever

damage they may have done to the character of poor Rene de Lesperon

ere they departed, they were not there, at all events, to denounce

me for an impostor. With a mental apology to the shade of the

departed Lesperon for all the discredit I was bringing down upon

his name, I broke the seal of that momentous epistle, which enclosed

a length of some thirty-two inches of string.

Monsieur [I read], wherever I may chance to meet you it shall be my

duty to kill you.

A rich beginning, in all faith! If he could but maintain that

uncompromising dramatic flavour to the end, his epistle should be

worth the trouble of deciphering, for he penned a vile scrawl of

pothooks.

It is because of this [the letter proceeded] that I have refrained

from coming face to face with you this morning. The times are too

troublous and the province is in too dangerous a condition to admit

of an act that might draw the eyes of the Keeper of the Seals upon

Lavedan. To my respect, then, to Monsieur le Vicomte and to my own

devotion to the Cause we mutually serve do you owe it that you still

live. I am on my way to Spain to seek shelter there from the King’s

vengeance.

To save myself is a duty that I owe as much to myself as to the

Cause. But there is another duty, one that I owe my sister, whom

you have so outrageously slighted, and this duty, by God’s grace, I

will perform before I leave. Of your honour, monsieur, we will not

speak, for reasons into which I need not enter, and I make no appeal

to it. But if you have a spark of manhood left, if you are not an

utter craven as well as a knave, I shall expect you on the day after

tomorrow, at any hour before noon, at the Auberge de la Couronne at

Grenade. There, monsieur, if you please, we will adjust our

differences. That you may come prepared, and so that no time need

be wasted when we meet, I send you the length of my sword.

Thus ended that angry, fire-breathing epistle. I refolded it

thoughtfully, then, having taken my resolve, I leapt from the bed

and desired Anatole to assist me to dress.

I found the Vicomte much exercised in mind as to the meaning of

Marsac’s extraordinary behaviour, and I was relieved to see that he,

at least, could conjecture no cause for it. In reply to the

questions with which he very naturally assailed me, I assured him

that it was no more than a matter of a misunderstanding; that

Monsieur de Marsac had asked me to meet him at Grenade in two days’

time, and that I should then, no doubt, be able to make all clear.

Meanwhile, I regretted the incident, since it necessitated my

remaining and encroaching for two days longer upon the Vicomte’s

hospitality. To all this, however, he made the reply that I

expected, concluding with the remark that for the present at least

it would seem as if the Chevalier de Saint-Eustache had been

satisfied with creating this trouble betwixt myself and Marsac.

From what Anatole had said, I had already concluded that Marsac had

exercised the greatest reticence. But the interview between his

sister and Roxalanne filled me with the gravest anxiety. Women are

not wont to practise the restraint of men under such circumstances,

and for all that Mademoiselle de Marsac may not have expressed it

in so many words that I was her faithless lover, yet women are

quick to detect and interpret the signs of disorders springing from

such causes, and I had every fear that Roxalanne was come to the

conclusion that I had lied to her yesternight. With an uneasy

spirit, then, I went in quest of her, and I found her walking in

the old rose garden behind the chateau.

She did not at first remark my approach, and I had leisure for some

moments to observe her and to note the sadness that dwelt in her

profile and the listlessness of her movements. This, then, was my

work - mine, and that of Monsieur de Chatellerault, and those other

merry gentlemen who had sat at my table in Paris nigh upon a month

ago.

I moved, and the gravel crunched under my foot, whereupon she turned,

and, at sight of me advancing towards her, she started. The blood

mounted to her face, to ebb again upon the instant, leaving it paler

than it had been. She made as if to depart; then she appeared to

check herself, and stood immovable and outwardly calm, awaiting my

approach.

But her eyes were averted, and her bosom rose and fell too swiftly

to lend colour to that mask of indifference she hurriedly put on.

Yet, as I drew nigh, she was the first to speak, and the triviality

of her words came as a shock to me, and for all my knowledge of

woman’s way caused me to doubt for a moment whether perhaps her

calm were not real, after all.

“You are a laggard this morning, Monsieur de Lesperon.” And, with

a half laugh, she turned aside to break a rose from its stem.

“True,” I answered stupidly; “I slept overlate.”

“A thousand pities, since thus you missed seeing Mademoiselle de

Marsac. Have they told you that she was here?”

“Yes, mademoiselle. Stanislas de Marsac left a letter for me.”

“You will regret not having seen them, no doubt?” quoth she.

I evaded the interrogative note in her voice. “That is their fault.

They appear to have preferred to avoid me.”

“Is it matter for wonder?” she flashed, with a sudden gleam of fury

which she as suddenly controlled. With the old indifference, she

added, “You do not seem perturbed, monsieur?”

“On the contrary, mademoiselle; I am very deeply perturbed.”

“At not having seen your betrothed?” she asked, and now for the

first time her eyes were raised, and they met mine with a look that

was a stab.

“Mademoiselle, I had the honour of telling you yesterday that I had

plighted my troth to no living woman.”

At that reminder of yesterday she winced, and I was sorry that I

had uttered it, for it must have set the wound in her pride

a-bleeding again. Yesterday I had as much as told her that I loved

her, and yesterday she had as much as answered me

Comments (0)