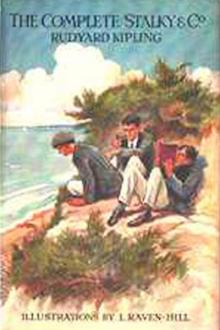

Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

“You remember Mrs. Oliphant’s ‘Beleaguered City’ that you lent me last term?” said. Beetle.

The Padre nodded.

“I got the notion out of that. Only, instead of a city, I made it the Coll. in a fog—besieged by ghosts of dead boys, who hauled chaps out of their beds in the dormitory. All the names are quite real. You tell it in a whisper, you know with the names. Orrin didn’t like it one little bit. None of ‘em have ever let me finish it. It gets just awful at the end part.”

“But why in the world didn’t you explain to Mr. Prout, instead of leaving him under the impression—?”

“Padre Sahib,” said McTurk, “it isn’t the least good explainin’ to Mr. Prout. If he hasn’t one impression, he’s bound to have another.”

“He’d do it with the best o’ motives. He’s inloco_parentis_,” purred Stalky.

“You young demons!” the Reverend John replied. “And am I to understand that the–the usury business was another of your housemaster’s impressions?”

“Well—we helped a little in that,” said Stalky. “I did owe Beetle two and fourpence at least, Beetle says I did, but I never intended to pay him. Then we started a bit of an argument on the stairs, and—and Mr. Prout dropped into it accidental. That was how it was, Padre. He paid me cash down like a giddy Dook (stopped it out of my pocket-money just the same), and Beetle gave him my note-of-hand all correct. I don’t know what happened after that.”

“I was too truthful,” said Beetle. “I always am. You see, he was under an impression, Padre, and I suppose I ought to have corrected that impression; but of course I couldn’t be quite certain that his house wasn’t given over to money-lendin’, could I? I thought the house-prefects might know more about it than I did. They ought to. They’re giddy palladiums of public schools.”

“They did, too—by the time they’d finished,” said McTurk. “As nice a pair of conscientious, well-meanin’, upright, pure-souled boys as you’d ever want to meet, Padre. They turned the house upside down —Harrison and Craye–with the best motives in the world.”

“They said so. ‘They said it very loud and clear. They went and shouted in our ear,’” said Stalky.

“My own private impression is that all three of you will infallibly be hanged,” said the Reverend John.

“Why, we didn’t do anything,” McTurk replied. “It was all Mr. Prout. Did you ever read a book about Japanese wrestlers? My uncle–he’s in the Navy—gave me a beauty once.”

“Don’t try to change the subject, Turkey.”

“I’m not, sir. I’m givin’ an illustration—same as a sermon. These wrestler-chaps have got sort sort of trick that lets the other chap do all the work. Than they give a little wriggle, and he upsets himself. It’s called shibbuwichee or tokonoma, or somethin’. Mr. Prout’s a shibbuwicher. It isn’t our fault.”

“Did you suppose we went round corruptin’ the minds of the fags? “said Beetle. “They haven’t any, to begin with; and if they had, they’re corrupted long ago. I’ve been a fag, Padre.”

“Well, I fancied I knew the normal range of your iniquities; hut if you take so much trouble to pile up circumstantial evidence against yourselves, you can’t blame any one if—”

“We don’t blame any one, Padre. We haven’t said a word against Mr. Prout, have we?” Stalky looked at the others. “We love him. He hasn’t a notion how we love him.”

“H’m! You dissemble your love very well. Have you ever thought who got you turned out of your study in the first place?”

“It was Mr. Prout turned us out,” said Stalky, with significance.

“Well, I was that man. I didn’t mean it; but some words of mine, I’m afraid, gave Mr. Prout the impression—”

Number Five laughed aloud.

“You see it’s just the same thing with you, Padre,” said McTurk. “He is quick to get an impression, ain’t he? But you mustn’t think we don’t love him, ‘cause we do. There isn’t an ounce of vice about him.”

A double knock fell on the door.

“The Head to see Number Five study in his study at once,” said the voice of Foxy, the school sergeant.

“Whew!” said the Reverend John. “It seems to me that there is a great deal of trouble coming for some people.”

“My word! Mr. Prout’s gone and told the Head,” said Stalky. “He’s a moral double-ender. Not fair, luggin’ the Head into a house-row.”

“I should recommend a copy-book on a—h’m—safe and certain part,” said the Reverend John disinterestedly.

“Huh! He licks across the shoulders, an’ it would slam like a beastly barn-door,” said Beetle. “Good-night, Padre. We’re in for it.”

Once more they stood in the presence of the Head—Belial, Mammon, and Lucifer. But they had to deal with a man more subtle than them all. Mr. Prout had talked to him, heavily and sadly, for half an hour; and the Head had seen all that was hidden from the housemaster.

“You’ve been bothering Mr. Prout,” he said pensively. “Housemasters aren’t here to be bothered by boys more than is necessary. I don’t like being bothered by these things. You are bothering me. That is a very serious offense. You see it?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, now, I purpose to bother you, on personal and private grounds, because you have broken into my time. You are much too big to lick, so I suppose I shall have to mark my displeasure in some other way. Say, a thousand lines apiece, a week’s gating, and a few things of that kind. Much too big to lick, aren’t you?”

“Oh, no, sir,” said Stalky cheerfully; for a week’s gating in the summer term is serious.

“Ve-ry good. Then we will do what we can. I wish you wouldn’t bother me.”

It was a fair, sustained, equable stroke, with a little draw to it, hut what they felt most was his unfairness in stopping to talk between executions. Thus: “Among the—lower classes this would lay me open to a charge of—assault. You should be more grateful for your—privileges than you are. There is a limit—one finds it by experience, Beetle—beyond which it is never safe to pursue private vendettas, because—don’t move—sooner or later one comes—into collision with the—higher authority, who has studied the animal. Etego_—McTurk, please—inArcadia_vixi_. There’s a certain flagrant injustice about this that ought to appeal to—your temperament. And that’s all! You will tell your housemaster that you have been formally caned by me.”

“My word!” said McTurk, wriggling his shoulder-blades all down the corridor. “That was business! The Prooshan Bates has an infernal straight eye.”

“Wasn’t it wily of me to ask for the lickin’,” said Stalky, “instead of those impots?”

“Rot! We were in for it from the first. I knew the look of his old eye,” said Beetle. “I was within an inch of blubbing.”

“Well, I didn’t exactly smile,” Stalky confessed.

“Let’s go down to the lavatory and have a look at the damage. One of us can hold the glass and t’others can squint.”

They proceeded on these lines for some ten minutes. The wales were very red and very level. There was not a penny to choose between any of them for thoroughness, efficiency, and a certain clarity of outline that stamps the work of the artist.

“What are you doing down there?” Mr. Prout was at the head of the lavatory stairs, attracted by the noise of splashing.

“We’ve only been caned by the Head, sir, and we’re washing off the blood. The Head said we were to tell you. We were coming to report ourselves in a minute, sir. (_Sotto_voce_.) That’s a score for Heffy!”

“Well, he deserves to score something, poor devil,” said McTurk, putting on his shirt. “We’ve sweated a stone and a half off him since we began.”

“But look here, why aren’t we wrathy with the Head? He said it was a flagrant injustice. So it is!” said Beetle.

“Dear man,” said McTurk, and vouchsafed no further answer.

It was Stalky who laughed till he had to hold on by the edge of a basin.

“You are a funny ass! What’s that for?” said Beetle.

“I’m—I’m thinking of the flagrant injustice of it!”

THE MORAL REFORMERS.

There was no disguising the defeat. The victory was to Prout, but they grudged it not. If he had broken the rules of the game by calling in the Head, they had had a good run for their money.

The Reverend John sought the earliest opportunity of talking things over. Members of a bachelor Common-room, of a school where masters’ studies are designedly dotted among studies and form-rooms, can, if they choose, see a great deal of their charges. Number Five had spent some cautious years in testing the Reverend John. He was emphatically a gentleman. He knocked at a study door before entering; he comported himself as a visitor and not a strayed lictor; he never prosed, and he never carried over into official life the confidences of idle hours. Prout was ever an unmitigated nuisance; King came solely as an avenger of blood; even little Hartopp, talking natural history, seldom forgot his office; but the Reverend John was a guest desired and beloved by Number Five.

Behold him, then, in their only arm-chair, a bent briar between his teeth, chin down in three folds on his clerical collar, and blowing like an amiable whale, while Number Five discoursed of life as it appeared to them, and specially of that last interview with the Head—in the matter of usury.

“One licking once a week would do you an immense amount of good,” he said, twinkling and shaking all over; “and, as you say, you were entirely in the right.”

“Ra-ather, Padre! We could have proved it if he’d let us talk,” said Stalky; “but he didn’t. The Head’s a downy bird.”

“He understands you perfectly. Ho! ho! Well, you worked hard enough for it.”

“But he’s awfully fair. He doesn’t lick a chap in the morning an’ preach at him in the afternoon,” said Beetle.

“He can’t; he ain’t in Orders, thank goodness,” said McTurk. Number Five held the very strongest views on clerical head-masters, and were ever ready to meet their pastor in argument.

“Almost all other schools have clerical Heads,” said the Reverend John gently.

“It isn’t fair on the chaps,” Stalky replied. “Makes ‘em sulky. Of course it’s different with you, sir. You belong to the school—same as we do. I mean ordinary clergymen.”

“Well, I am a most ordinary clergyman; and Mr. Hartopp’s in Orders, too.”

“Ye—es, but he took ‘em after he came to the Coll. We saw him go up for his exam. That’s all right,” said Beetle. “But just think if the Head went and got ordained!”

“What would happen, Beetle?”

“Oh, the Coll. ‘ud go to pieces in a year, sir. There’s no doubt o’ that.”

“How d’you know?” The Reverend John was smiling.

“We’ve been here nearly six years now. There are precious few things about the Coll. we don’t know,” Stalky replied. “Why, even you came the term after I did, sir. I remember your asking our names in form your first lesson. Mr. King, Mr. Prout, and the Head, of course, are the only masters senior to us—in that way.”

“Yes, we’ve changed a good deal—in Common-room.”

“Huh!” said Beetle with a grunt. “They came here, an’ they went away to get married. Jolly good riddance, too!”

“Doesn’t our Beetle hold with matrimony?”

“No, Padre; don’t make fun of me. I’ve met chaps in the holidays who’ve got married housemasters. It’s perfectly awful! They have babies and teething and measles and all that sort of thing right bung in the school; and the masters’ wives give tea-parties—tea-parties, Padre!—and ask the chaps

Comments (0)