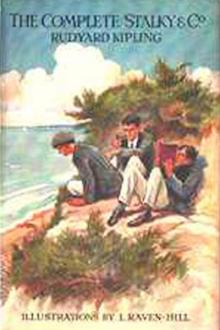

Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

“What for?” Beetle entered joyously into the libel.

“Forty shillin’s or a month for hackin’ the chucker-out of the Pavvy on the shins. Bates always has a spree when he goes to town. Wish he was back, though. I’m about sick o’ King’s ‘whips an’ scorpions’ an’ lectures on public-school spirit—yah!—and scholarship!”

“‘Crass an’ materialized brutality of the middle-classes—readin’ solely for marks. Not a scholar in the whole school,’” McTurk quoted, pensively boring holes in the mantelpiece with a hot poker.

“That’s rather a sickly way of spending an afternoon. Stinks too. Let’s come out an’ smoke. Here’s a treat.” Stalky held up a long Indian cheroot. “‘Bagged it from my pater last holidays. I’m a bit shy of it though; it’s heftier than a pipe. We’ll smoke it palaver-fashion. Hand it round, eh? Let’s lie up behind the old harrow on the Monkey-farm Road.”

“Out of bounds. Bounds beastly strict these days, too. Besides, we shall cat.” Beetle sniffed the cheroot critically. “It’s a regular Pomposo Stinkadore.”

“You can; I shan’t. What d’you say, Turkey?”

“Oh, may’s well, I s’pose.”

“Chuck on your cap, then. It’s two to one. Beetle, out you come!”

They saw a group of boys by the notice-board in the corridor; little Foxy, the school sergeant, among them.

“More bounds, I expect,” said Stalky. “Hullo, Foxibus, who are you in mournin’ for?” There was a broad band of crape round Foxy’s arm.

“He was in my old regiment,” said Foxy, jerking his head towards the notices, where a newspaper cutting was thumb-tacked between callover lists.

“By gum!” quoth Stalky, uncovering as he read. “It’s old Duncan—Fat-Sow Duncan—killed on duty at something or other Kotal. ‘Rallyin’his_menwith conspicuousgallantry._’ He would, of course. ‘Thebodywasrecovered_.’ That’s all right. They cut ‘em up sometimes, don’t they, Foxy?”

“Horrid,” said the sergeant briefly.

“Poor old Fat-Sow! I was a fag when he left. How many does that make to us, Foxy?”

“Mr. Duncan, he is the ninth. He come here when he was no bigger than little Grey tertius. My old regiment, too. Yiss, nine to us, Mr. Corkran, up to date.”

The boys went out into the wet, walking swiftly.

“Wonder how it feels—to be shot and all that,” said Stalky, as they splashed down a lane. “Where did it happen, Beetle?”

“Oh, out in India somewhere. We’re always rowin’ there. But look here, Stalky, what is the good o’ sittin’ under a hedge an’ cattin’? It’s be-eastly cold. It’s be-eastly wet, and we’ll be collared as sure as a gun.”

“Shut up! Did you ever know your Uncle Stalky get you into a mess yet?” Like many other leaders, Stalky did not dwell on past defeats. They pushed through a dripping hedge, landed among water-logged clods, and sat down on a rust-coated harrow. The cheroot burned with sputterings of saltpetre. They smoked it gingerly, each passing to the other between dosed forefinger and thumb.

“Good job we hadn’t one apiece, ain’t it?” said Stalky, shivering through set teeth. To prove his words he immediately laid all before them, and they followed his example…

“I told you,” moaned Beetle, sweating clammy drops. “Oh, Stalky, you are a fool!”

“Jecat_, tucat_, ilcat_. Nous cattons!” McTurk handed up his contribution and lay hopelessly on the cold iron.

“Something’s wrong with the beastly thing. I say, Beetle, have you been droppin’ ink on it?”

But Beetle was in no case to answer. Limp and empty, they sprawled across the harrow, the rust marking their ulsters in red squares and the abandoned cheroot-end reeking under their very cold noses. Then—they had heard nothing—the Head himself stood before them—the Head who should have been in town bribing examiners—the Head fantastically attired in old tweeds and a deer-stalker!

“Ah,” he said, fingering his mustache. “Very good. I might have guessed who it was. You will go back to the College and give my compliments to Mr. King and ask him to give you an extra-special licking. You will then do me five hundred lines. I shall be back to-morrow. Five hundred lines by five o’clock to-morrow. You are also gated for a week. This is not exactly the time for breaking bounds. Extra-special, please.”

He disappeared over the hedge as lightly as he had come. There was a murmur of women’s voices in the deep lane.

“Oh, you Prooshan brute!” said McTurk as the voices died away. “Stalky, it’s all your silly fault.”

“Kill him! Kill him!” gasped Beetle.

“I ca-an’t. I’m going to cat again… I don’t mind that, but King’ll gloat over us horrid. Extra-special, ooh!”

Stalky made no answer—not even a soft one. They went to College and received that for which they had been sent. King enjoyed himself most thoroughly, for by virtue of their seniority the boys were exempt from his hand, save under special order. Luckily, he was no expert in the gentle art.

“‘Strange, how desire doth outrun performance,’” said Beetle irreverently, quoting from some Shakespeare play that they were cramming that term. They regained their study and settled down to the imposition.

“You’re quite right, Beetle.” Stalky spoke in silky and propitiating tones. “Now, if the Head had sent us up to a prefect, we’d have got something to remember!”

“Look here,” McTurk began with cold venom, “we aren’t goin’ to row you about this business, because it’s too bad for a row; but we want you to understand you’re jolly well excommunicated, Stalky. You’re a plain ass.”

“How was I to know that the Head ‘ud collar us? What was he doin’ in those ghastly clothes, too?”

“Don’t try to raise a side-issue,” Beetle grunted severely.

“Well, it was all Stettson major’s fault. If he hadn’t gone an’ got diphtheria ‘twouldn’t have happened. But don’t you think it rather rummy—the Head droppin’ on us that way?”

“Shut up! You’re dead!” said Beetle. “We’ve chopped your spurs off your beastly heels. We’ve cocked your shield upside down and–and I don’t think you ought to be allowed to brew for a month.”

“Oh, stop jawin’ at me. I want—”

“Stop? Why—why, we’re gated for a week.” McTurk almost howled as the agony of the situation overcame him. “A lickin’ from King, five hundred lines, and a gatin’. D’you expect us to kiss you, Stalky, you beast?”

“Drop rottin’ for a minute. I want to find out about the Head bein’ where he was.”

“Well, you have. You found him quite well and fit. Found him makin’ love to Stettson major’s mother. That was her in the lane—I heard her. And so we were ordered a lickin’ before a day-boy’s mother. Bony old widow, too,” said McTurk. “Anything else you’d like to find out?”

“I don’t care. I swear I’ll get even with him some day,” Stalky growled.

“Looks like it,” said McTurk. “Extra-special, week’s gatin’ and five hundred… and now you’re goin’ to row about it! Help scrag him, Beetle!” Stalky had thrown his Virgil at them.

The Head returned next day without explanation, to find the lines waiting for him and the school a little relaxed under Mr. King’s viceroyalty. Mr. King had been talking at and round and over the boys’ heads, in a lofty and promiscuous style, of public-school spirit and the traditions of ancient seats; for he always improved an occasion. Beyond waking in two hundred and fifty young hearts a lively hatred of all other foundations, he accomplished little—so little, indeed, that when, two days after the Head’s return, he chanced to come across Stalky & Co., gated but ever resourceful, playing marbles in the corridor, he said that he was not surprised—not in the least surprised. This was what he had expected from persons of their morale.

“But there isn’t any rule against marbles, sir. Very interestin’ game,” said Beetle, his knees white with chalk and dust. Then he received two hundred lines for insolence, besides an order to go to the nearest prefect for judgment and slaughter.

This is what happened behind the closed doors of Flint’s study, and Flint was then Head of the Games:—

“Oh, I say, Flint. King has sent me to you for playin’ marbles in the corridor an’ shoutin’ ‘alley tor’ an’ ‘knuckle down.’”

“What does he suppose I have to do with that?” was the answer.

“Dunno. Well?” Beetle grinned wickedly. “What am I to tell him? He’s rather wrathy about it.”

“If the Head chooses to put a notice in the corridor forbiddin’ marbles, I can do something; but I can’t move on a housemaster’s report. He knows that as well as I do.”

The sense of this oracle Beetle conveyed, all unsweetened, to King, who hastened to interview Flint.

Now Flint had been seven and a half years at the College, counting six months with a London crammer, from whose roof he had returned, homesick, to the Head for the final Army polish. There were four or five other seniors who bad gone through much the same mill, not to mention boys, rejected by other establishments on account of a certain overwhelmingness, whom the Head had wrought into very fair shape. It was not a Sixth to be handled without gloves, as King found.

“Am I to understand it is your intention to allow board-school games under your study windows, Flint? If so, I can only say—” He said much, and Flint listened politely.

“Well, sir, if the Head sees fit to call a prefects’ meeting we are bound to take the matter up. But the tradition of the school is that the prefects can’t move in any matter affecting the whole school without the Head’s direct order.”

Much more was then delivered, both sides a little losing their temper.

After tea, at an informal gathering of prefects in his study, Flint related the adventure.

“He’s been playin’ for this for a week, and now he’s got it. You know as well as I do that if he hadn’t been gassing at us the way he has, that young devil Beetle wouldn’t have dreamed of marbles.”

“We know that,” said Perowne, “but that isn’t the question. On Flint’s showin’ King has called the prefects names enough to justify a first-class row. Crammers’ rejections, ill-regulated hobble-de-hoys, wasn’t it? Now it’s impossible for prefects—”

“Rot,” said Flint. “King’s the best classical cram we’ve got; and ‘tisn’t fair to bother the Head with a row. He’s up to his eyes with extra-tu. and Army work as it is. Besides, as I told King, we aren’t a public school. We’re a limited liability company payin’ four per cent. My father’s a shareholder, too.”

“What’s that got to do with it?” said Venner, a red-headed boy of nineteen.

“Well, seems to me that we should be interferin’ with ourselves. We’ve got to get into the Army or—get out, haven’t we? King’s hired by the Council to teach us. All the rest’s gumdiddle. Can’t you see?”

It might have been because he felt the air was a little thunderous that the Head took his after-dinner cheroot to Flint’s study; but he so often began an evening in a prefect’s room that nobody suspected when he drifted in pensively, after the knocks that etiquette demanded.

“Prefects’ meeting?” A cock of one wise eyebrow.

“Not exactly, sir; we’re just talking things over. Won’t you take the easy chair?”

“Thanks. Luxurious infants, you are.” He dropped into Flint’s big half-couch and puffed for a while in silence. “Well, since you’re all here, I may confess that I’m the mute with the bowstring.”

The young faces grew serious. The phrase meant that certain of their number would be withdrawn from all further games for extra-tuition. It might also mean future success at Sandhurst; but it was present ruin for the First Fifteen.

“Yes, I’ve come for my pound of flesh. I ought to have had you out before the Exeter match; but it’s our sacred duty to beat

Comments (0)