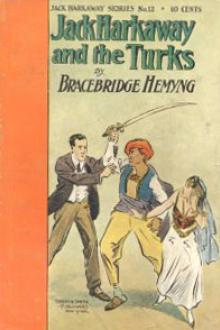

Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

- Performer: -

Book online «Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Bracebridge Hemyng

The Englishman's eyes sparkled viciously.

"I will, I will."

"Let me know the result, and should you want my aid, you will note well the house on leaving so as to know where to return."

"Yes. What is your name?" demanded the Englishman.

"Hadji Nasir Ali," was the reply; "and yours?"

The other hesitated.

"Don't give it unless you feel it is safe," said the Turk.

"There's no harm in your knowing it," returned the Englishman. "My name is Harkaway."

"Hark-a-way?"

"In one word."

"I see. Farewell, then."

"Farewell."

And the interview was concluded.

"That letter is a splendid dodge. Look out, Master Jack Harkaway, look out, for I mean to cry quits now, or my name is not Herbert Murray," muttered the Englishman, as he walked away.

But how Herbert Murray had got to Turkey requires some explanation.

It will be within our readers' recollection that after his unsuccessful attempt on Chivey's life, and the adventure of the groom with the old Spaniard, Murray found himself on board the same ship as his groom.

He resolved to make the best of this circumstance, as it could not now be altered.

A few days after leaving the Spanish coast they put into one of the Mediterranean ports, and there heard that young Jack and his friends had gone on to Turkey.

"I'll follow them!" exclaimed Murray. "I can do as I like now the governor's gone and I've plenty of tin, so look out for yourself, Jack Harkaway."

Murray's ship was delayed by adverse weather, but at length reached port, and Herbert had scarcely put foot on shore, when he beheld young Jack, the object of his deadly hate, walking coolly down the street smoking a cigar.

This so enraged Murray that he hastened to disguise himself in Oriental attire, and then made the attempt on Jack's life which we have related.

That same night a man was found dead on the threshold of the house in which Jack Harkaway and his friends resided.

How he had died no one could imagine, for he had not a scratch on his body.

Yet, stay.

There was a scratch.

Just that and no more.

In his fast-clenched hand was found an envelope addressed to Mr. John Harkaway, and on a closer examination a pin's point was seen sticking through the paper.

This had just pricked the messenger's hand.

So slightly that, had not the tiny wound turned slightly blue, it would have entirely escaped notice.

Jack was now aware that he had in Turkey a deadly enemy, but who he was he could not yet tell.

When the men of skill assembled around the body, they were puzzled to assign a cause of death until one of them suggested it was apoplexy. So apoplexy it was unanimously set down for.

There was no more fuss made.

The man was only a poor devil of a Circassian, who got a precarious livelihood as a public messenger. So they

"Rattled his bones

Over the stones,

Like those of a pauper whom nobody owns."

And meanwhile, his murderer went his way.

"Fortunate I gave the name of Harkaway to that old professional poisoner, for they will never trace this job to me."

There was, however, one result from this using of Jack Harkaway's name which Herbert Murray certainly never contemplated.

But of this we must speak hereafter.

In spite of his knowledge of the fact that he had enemies following his footsteps, our hero would not remain in the house.

"I am quite as safe in the street as here," said he, in reply to Harry Girdwood's representations of the danger he ran, "and I am sure, old boy, you would not have me show the white feather."

"You never did that, and never will; but you need not run into unnecessary danger."

"'Thrice is he armed who has his quarrel just,' and his revolver well loaded. Ta-ta! I am just going to stroll down to this Turkish substitute for a postoffice, and see if last night's steamer brought any letters."

So Jack strolled down accordingly, and found a letter for him.

His heart beat with joy as he recognised the handwriting, and he hurried home to read it.

On breaking open the envelope, out tumbled a beautiful carte de visite portrait, a copy of which we are able to give, as we still thoroughly retain young Jack's friendship and confidence.

He kissed it till he began to fear he might spoil the likeness, and then placing it on the table before him, began to read.

And this is the letter—

"Dear Jack,—You very naughty boy. Where have you been, and why have you not written? I have a great mind to scold you, sir; but on second thoughts, I think I had better leave the task of correcting you to your parents, who, perhaps, have more influence with you than I have. You don't know, dear, how anxious we have all been about you. Poor Mr. Mole has started in search of you. Have you seen him yet?—and if you don't write soon, I shall feel obliged to try and find out what has become of you, for I almost begin to fear that some fair Turkish or Circassian girl——"

"The deuce!" Jack thought; "she can't have heard any thing of that affair yet. If Mole has written, the letter could not have reached England on the 20th of last month."

Then he continued—

"——has stolen your heart, and Harry Girdwood's too. Why, poor Paquita always has red eyes when she gets up. So, darling Jack, do write at once, and cheer our hearts. I can't help writing like this, for I feel so fearful that something has happened to you. So be a dear, good boy, and send a full account of all your doings to your father, and just a few lines to

"Your ever faithful and affectionate.

"Emily.

"P.S.—I was just reading this over to see if I had been too cross, when your father came in with a photographer, who took my portrait without my knowing anything about it. Do you think it like me, sir?"

Then followed three or four of those blots which ladies call "kisses."

CHAPTER LXXXI.

MR. MOLE AGAIN OUT OF LUCK.

Herbert Murray, attended by Chivey, was strolling down the principal street of the town, smoking his cigar, thinking how he could yet serve out young Jack, when he suddenly saw, on in front, the figure of an elderly man, who appeared to walk with difficulty.

He made such uncertain steps and singular movements, as he hobbled along by the aid of a stick, that the effect, however painful to him, was ludicrous to the onlookers.

"Why, blest if it ain't old Mole, the man who came to bid young Harkaway and his friends good-bye when we sailed," cried Chivey.

"Or his ghost," said Murray.

"I'll have a lark with him, sir," said the tiger, laying his finger aside his nose, and winking knowingly. "You see!"

And walking nimbly and on tiptoe behind the old man, he soon caught up to him without his knowing it.

Murray halted at a little distance, ready to behold and enjoy the discomfiture of Mole.

The reader must be informed that the venerable Isaac was then experimenting upon a new substitute for those unfortunate much damaged members, his cork legs.

An American genius, with whom he had recently made acquaintance in the town, had induced Mole to try a pair of his "new patent-elastic-spring- non-fatiguing-self-regulating-undistinguishable-everlasting cork legs."

The inventor had helped Mr. Mole to put on these formidable "understandings," and given him every instruction with regard to their management.

"They'll be a little creaky at first," said the American; "nothing in nature works slick when it's quite new, but when you get 'em well into wear, they'll go along like greased lightning; now try them, old hoss."

Creaky indeed they were, for they made a noise almost as loud as a railway break; but what was even worse was that the Yankee had failed to inform Mole of the fact that the "new patent" etc., were only fitted to act perfectly on a smooth surface.

Now the roadway, or footway—for they are all the same in those old Turkish towns—are the very reverse of smooth, being principally composed of round nubbly stones.

Consequently Mole's locomotion was the reverse of pleasant.

Chivey crept up behind the old schoolmaster, and seizing an opportunity and one of his legs, gave it a pull, which caused Mole to roar with fright.

Down, of course, came Mole on the nubbly pavement, but Chivey didn't have exactly the fun he expected, for instead of his getting safely away, Mole fell on him.

"Oh, it's you, is it? You, the bad servant of a bad man's wicked son," exclaimed the angered tutor; "it's you who dare to set upon defenceless age and innocence, with its new cork legs on? Very good. Then take that, and I hope you won't like it."

Whereat he began pommelling away at Chivey.

Chivey roared with all his might, till a small crowd of wondering onlookers began to collect.

"What do you mean by daring to assault my servant in this manner?" asked Murray sternly, as he came up.

"He attacked me first," protested Mole; "and it's my belief you set him on to do it."

"How dare you insinuate——" began Murray, and he violently shook the old man by the collar.

But there was more spirit in Mole than Herbert was prepared for.

By the aid of a post, the old man managed to struggle to his feet, and leaning against this, he felt he could defy the enemy.

"My lad," he said, "it's evident that you didn't get enough flogging when you were at school, or you'd know better manners; I must take you in hand a bit now, sir, there!"

With his stick he gave a cut to the palm of Murray's hand, just as he was wont to do to refractory pupils in the old days.

Murray was livid with rage.

Chivey, now rather afraid of Mole, didn't interfere.

"Come on, if you like, and have some more," said Mole, and shaking his stick at both of them, he again urged on his wild career.

Very wild indeed it was, too.

Mole's patent legs, which outwardly looked natural ones, were indeed self-regulating, for they were soon utterly beyond the control of the wearer; they seemed to be possessed of wills of their own; one wished to go to the right, the other to the left.

Sometimes they would carry him along in double quick march time, and anon halt, beyond all his power of budging.

Of course the boys of the town were attracted by the stranger's singular movements, and began to hoot and jeer.

The merchants were interrupted at their calculations, the bazaar keepers came to their doors, long pipe in mouth, to see what the "son of Sheitan" was about.

Mole was red in the face with such hard work.

"Confound the Turks," he cried; "why don't they make their roads smoother? Oh, dear, I wish I could manage these unhappy legs; there they go."

By this time the crowd had become unpleasantly dense around him.

"Out of the way, un-Christian dogs," cried Mole, flourishing his stick round his head; "I'm an Englishman, and I've a right to—hallo! there it goes again."

"'Out of the way, unchristian dogs,' cried Mole".--Tinker, Vol.II.

"'out of the way, unchristian dogs,' cried mole."—Tinker, vol. ii.

For here his left leg took two steps to the right, and he came down with all his weight upon the toe of a white-bearded Alla-hissite.

"Son of a dog," growled the old Turk, as he rubbed his pet corn in agony; "may your mother's grave be defiled, and the jackass bray over your father's bones."

"I really beg your pardon," began Mole, but just at this moment his right leg was taken with a spasmodic action, and began to stride along at a furious rate, creaking like mad.

Mole lost all control (if he ever had any) over his own movements, and was carried forward again, till he came where Herbert Murray and Chivey, having made a detour, happened to be just turning the corner of the street.

"Stop me," yelled Mole, as he flourished his stick over his head; "my spring legs are doing what they like

Comments (0)