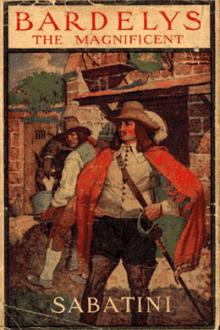

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

enough of my condition, and well might Chatellerault stare at

beholding me so manifestly a prisoner.

Even as I watched him, he appeared to start at something that

Saint-Eustache was saying, and a curious change spread over his face.

Its whilom expression had been rather one of dismay; for, having

believed me dead, he no doubt accounted his wager won, whereas seeing

me alive had destroyed that pleasant conviction. But now it took on

a look of relief and of something that suggested malicious cunning.

“That,” said Castelroux in my ear, “is the King’s commissioner.

Did I not know it? I never waited to answer him, but, striding across

the room, I held out my hand over the table - to Chatellerault.

“My dear Comte,” I cried, “you are most choicely met.”

I would have added more, but there was something in his attitude

that silenced me. He had turned half from me, and stood now, hand

on hip, his great head thrown back and tilted towards his shoulder,

his expression one of freezing and disdainful wonder.

Now, if his attitude filled me with astonishment and apprehension,

consider how these feelings were heightened by his words.

“Monsieur de Lesperon, I can but express amazement at your effrontery.

If we have been acquainted in the past, do you think that is a

sufficient reason for me to take your hand now that you have placed

yourself in a position which renders it impossible for His Majesty’s

loyal servants to know you?”

I fell back a pace, my mind scarce grasping yet the depths of this

inexplicable attitude.

“This to me, Chatellerault?” I gasped.

“To you?” he blazed, stirred to a sudden passion. “What else did

you expect, Monsieur de Lesperon?”

I had it in me to give him the lie, to denounce him then for a low,

swindling trickster. I understood all at once the meaning of this

wondrous make-believe. From Saint-Eustache he had gathered the

mistake there was, and for his wager’s sake he would let the error

prevail, and hurry me to the scaffold. What else might I have

expected from the man that had lured me into such a wager - a wager

which the knowledge he possessed had made him certain of winning?

Would he who had cheated at the dealing of the cards neglect an

opportunity to cheat again during the progress of the game?

As I have said, I had it in my mind to cry out that he lied - that

I was not Lesperon; that he knew I was Bardelys. But the futility

of such an outcry came to me simultaneously with the thought of it.

And, I fear me, I stood before him and his satellites - the mocking

Saint-Eustache amongst them - a very foolish figure.

“There is no more to be said,” I murmured at last.

“But there is!” he retorted. “There is much more to be said. You

shall render yet an account of your treason, and I am afraid, my

poor rebel, that your comely head will part company with your shapely

body. You and I will meet at Toulouse. What more is to be said

will be said in the Tribunal there.”

A chill encompassed me. I was doomed, it seemed. This man, ruling

the province pending the King’s arrival, would see to it that none

came forward to recognize me. He would expedite the comedy of my

trial, and close it with the tragedy of my execution. My professions

of a mistake of identity - if I wasted breath upon them would be

treated with disdain and disregarded utterly. God! What a position

had I got myself into, and what a vein of comedy ran through it -

grim, tragic comedy, if you will, yet comedy to all faith. The very

woman whom I had wagered to wed had betrayed me into the hands of

the very man with whom I laid my wager.

But there was more in it than that. As I had told Mironsac that

night in Paris, when the thing had been initiated, it was a duel

that was being fought betwixt Chatellerault and me - a duel for

supremacy in the King’s good graces. We were rivals, and he desired

my removal from the Court. To this end had he lured me into a

bargain that should result in my financial ruin, thereby compelling

me to withdraw from the costly life of the Luxembourg, and leaving

him supreme, the sole and uncontested recipient of our master’s

favour. Now into his hand Fate had thrust a stouter weapon and a

deadlier: a weapon which not only should make him master of the

wealth that I had pledged, but one whereby he might remove me for

all time, a thousandfold more effectively than the mere encompassing

of my ruin would have done.

I was doomed. I realized it fully and very bitterly.

I was to go out of the ways of men unnoticed and unmourned; as a

rebel, under the obscure name of another and bearing another’s sins

upon my shoulders, I was to pass almost unheeded to the gallows.

Bardelys the Magnificent - the Marquis Marcel Saint-Pol de Bardelys,

whose splendour had been a byword in France - was to go out like a

guttering candle.

The thought filled me with the awful frenzy that so often goes with

impotency, such a frenzy as the damned in hell may know. I forgot

in that hour my precept that under no conditions should a gentleman

give way to anger. In a blind access of fury I flung myself across

the table and caught that villainous cheat by the throat, before

any there could put out a hand to stop me.

He was a heavy man, if a short one, and the strength of his thick-set

frame was a thing abnormal. Yet at that moment such nervous power

did I gather from my rage, that I swung him from his feet as though

he had been the puniest weakling. I dragged him down on to the

table, and there I ground his face with a most excellent good-will

and relish.

“You liar, you cheat, you thief!” I snarled like any cross-grained

mongrel. “The King shall hear of this, you knave! By God, he shall!”

They dragged me from him at last - those lapdogs that attended him

—and with much rough handling they sent me sprawling among the

sawdust on the floor. It is more than likely that but for

Castelroux’s intervention they had made short work of me there and

then.

But with a bunch of Mordieus, Sangdieus, and Po’ Cap de Dieus, the

little Gascon flung himself before my prostrate figure, and bade

them in the King’s name, and at their peril, to stand back.

Chatellerault, sorely shaken, his face purple, and with blood

streaming from his nostrils, had sunk into a chair. He rose now,

and his first words were incoherent, raging gasps.

“What is your name, sir?” he bellowed at last, addressing the

Captain.

“Amedee de Mironsac de Castelroux, of Chateau Rouge in Gascony,”

answered my captor, with a grand manner and a flourish, and added,

“Your servant.”

“What authority have you to allow your prisoners this degree of

freedom?”

“I do not need authority, monsieur,” replied the Gascon.

“Do you not?” blazed the Count. “We shall see. Wait until I am in

Toulouse, my malapert friend.”

Castelroux drew himself up, straight as a rapier, his face slightly

flushed and his glance angry, yet he had the presence of mind to

restrain himself, partly at least.

“I have my orders from the Keeper of the Seals, to effect the

apprehension of Monsieur de Lesperon; and to deliver him up, alive

or dead, at Toulouse. So that I do this, the manner of it is my

own affair, and who presumes to criticize my methods censoriously

impugns my honour and affronts me. And who affronts me, monsieur,

be he whosoever he may be, renders me satisfaction. I beg that you

will bear that circumstance in mind.”

His moustaches bristled as he spoke, and altogether his air was very

fierce and truculent. For a moment I trembled for him. But the

Count evidently thought better of it than to provoke a quarrel,

particularly one in which he would be manifestly in the wrong,

King’s Commissioner though he might be. There was an exchange of

questionable compliments betwixt the officer and the Count,

whereafter, to avoid further unpleasantness, Castelroux conducted

me to a private room, where we took our meal in gloomy silence.

It was not until an hour later, when we were again in the saddle

and upon the last stage of our journey, that I offered Castelroux

an explanation of my seemingly mad attack upon Chatellerault.

“You have done a very rash and unwise thing, monsieur,” he had

commented regretfully, and it was in answer to this that I poured

out the whole story. I had determined upon this course while we

were supping, for Castelroux was now my only hope, and as we rode

beneath the stars of that September night I made known to him my

true identity.

I told him that Chatellerault knew me, and I informed him that a

wager lay between us - withholding the particulars of its nature

—which had brought me into Languedoc and into the position wherein

he had found and arrested me. At first he hesitated to believe me,

but when at last I had convinced him by the vehemence of my

assurances as much as by the assurances themselves, he expressed

such opinions of the Comte de Chatellerault as made my heart go out

to him.

“You see, my dear Castelroux, that you are now my last hope,” I said.

“A forlorn one, my poor gentleman!” he groaned.

“Nay, that need not be. My intendant Rodenard and some twenty of

my servants should be somewhere betwixt this and Paris. Let them

be sought for monsieur, and let us pray God that they be still in

Languedoc and may be found in time.”

“It shall be done, monsieur, I promise you,” he answered me solemnly.

“But I implore you not to hope too much from it. Chatellerault has

it in his power to act promptly, and you may depend that he will

waste no time after what has passed.”

“Still, we may have two or three days, and in those days you must

do what you can, my friend.”

“You may depend upon me,” he promised.

“And meanwhile, Castelroux,” said I, “you will say no word of this

to any one.”

That assurance also he gave me, and presently the lights of our

destination gleamed out to greet us.

That night I lay in a dank and gloomy cell of the prison of Toulouse,

with never a hope to bear company during those dark, wakeful hours.

A dull rage was in my soul as I thought of my position, for it had

not needed Castelroux’s recommendation to restrain me from building

false hopes upon his chances of finding Rodenard and my followers in

time to save me. Some little ray of consolation I culled, perhaps,

from my thoughts of Roxalanne. Out of the gloom of my cell my fancy

fashioned her sweet girl face and stamped it with a look of gentle

pity, of infinite sorrow for me and for the hand she had had in

bringing me to this.

That she loved me I was assured, and I swore that if I lived I would

win her yet, in spite of every obstacle that I myself had raised for

my undoing.

THE TRIBUNAL OF TOULOUSE

I had

Comments (0)