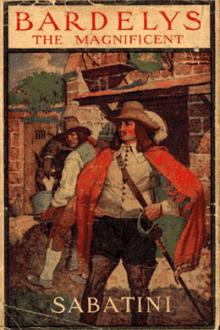

Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: 1406820563

Book online «Bardelys the Magnificent - Rafael Sabatini (affordable ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

you no more - you whom I had enshrined so in my heart.

“I called myself a little fool that morning for having dreamed that

you had come to care for me; my vanity I thought had deluded me

into imagining that your manner towards me had a tenderness that

spoke of affection. I was bitter with myself, and I suffered oh,

so much! Then later, when I was in the rose garden, you came to me.

“You remember how you seized me, and how by your manner you showed

me that it was not vanity alone had misled me. You had fooled me,

I thought; even in that hour I imagined you were fooling me; you

made light of me; and my sufferings were naught to you so that I

might give you some amusement to pass the leisure and monotony of

your sojourn with us.”

“Roxalanne - my poor Roxalanne!” I whispered.

“Then my bitterness and sorrow all turned to anger against you.

You had broken my heart, and I thought that you had done it

wantonly. For that I burned to punish you. Ah! and not only that,

perhaps. I think, too, that some jealousy drove me on. You had

wooed and slighted me, yet you had made me love you, and if you

were not for me I swore you should be for no other. And so, while

my madness endured, I quitted Lavedan, and telling my father that

I was going to Auch, to his sister’s house, I came to Toulouse and

betrayed you to the Keeper of the Seals.

“Scarce was the thing done than I beheld the horror of it, and I

hated myself. In my despair, I abandoned all idea of pursuing the

journey to Auch, but turned and made my way back in haste, hoping

that I might still come to warn you. But at Grenade I met you

already in charge of the soldiers. At Grenade, too I learnt the

truth - that you were not Lesperon. Can you not guess something of

my anguish then? Already loathing my act, and beside myself for

having betrayed you, think into what despair I was plunged by

Monsieur de Marsac’s intimation.

“Then I understood that for reasons of your own you had concealed

your identity. You were not perhaps, betrothed; indeed, I remembered

then how, solemnly you had sworn that you were not; and so I

bethought me that your vows to me may have been sincere and such as

a maid might honourably listen to.”

“They were, Roxalanne! they were!” I cried.

But she continued “That you had Mademoiselle de Marsac’s portrait

was something that I could not explain; but then I hear that you

had also Lesperon’s papers upon you; so that you may have become

possessed of the one with the others. And now, monsieur—”

She ceased, and there against my breast she lay weeping and weeping

in her bitter passion of regret, until it seemed to me she would

never regain her self-control.

“It has been all my fault, Roxalanne,” said I, “and if I am to pay

the price they are exacting, it will be none too high. I embarked

upon a dastardly business; which brought me to Languedoc under

false colours. I wish, indeed, that I had told you when first the

impulse to tell you came upon me. Afterwards it grew impossible.”

“Tell me now,” she begged. “Tell me who you are.”

Sorely was I tempted to respond. Almost was I on the point of

doing so, when suddenly the thought of how she might shrink from me,

of how, even then, she might come to think that I had but simulated

love for her for infamous purposes of gain, restrained and silenced

me. During the few hours of life that might be left me I would at

least be lord and master of her heart. When I was dead - for I had

little hope of Castelroux’s efforts - it would matter less, and

perhaps because I was dead she would be merciful.

“I cannot, Roxalanne. Not even now. It is too vile! If - if they

carry out the sentence on Monday, I shall leave a letter for you,

telling you everything.”

She shuddered, and a sob escaped her. From my identity her mind

fled back to the more important matter of my fate.

“They will not carry it out, monsieur! Oh, they till not! Say that

you can defend yourself, that you are not the man they believe you

to be!”

“We are in God’s hands, child. It may be that I shall save myself

yet. If I do, I shall come straight to you, and you shall know all

that there is to know. But, remember, child” - and raising her

face in my hands, I looked down into the blue of her tearful eyes -

“remember, little one, that in one thing I have been true and

honourable, and influenced by nothing but my heart - in my wooing

of you. I love you, Roxalanne, with all my soul, and if I should

die you are the only thing in all this world that I experience a

regret at leaving.”

“I do believe it; I do, indeed. Nothing can ever alter my belief

again. Will you not, then, tell me who you are, and what is this

thing, which you call dishonourable, that brought you into Languedoc?”

A moment again I pondered. Then I shook my head.

“Wait, child,” said I; and she, obedient to my wishes, asked no more.

It was the second time that I neglected a favourable opportunity of

making that confession, and as I had regretted having allowed the

first occasion to pass unprofited, so was I, and still more

poignantly, to regret this second silence.

A little while she stayed with me yet, and I sought to instil some

measure of comfort into her soul. I spoke of the hopes that I

based upon Castelroux’s finding friends to recognize me - hopes

that were passing slender. And she, poor child, sought also to

cheer me and give me courage.

“If only the King were here!” she sighed. “I would go to him, and

on my knees I would plead for your enlargement. But they say he is

no nearer than Lyons; and I could not hope to get there and back by

Monday. I will go to the Keeper of the Seals again, monsieur, and

I will beg him to be merciful, and at least to delay the sentence.”

I did not discourage her; I did not speak of the futility of such

a step. But I begged her to remain in Toulouse until Monday, that

she might visit me again before the end, if the end were to become

inevitable.

Then Castelroux came to reconduct her, and we parted. But she left

me a great consolation, a great strengthening comfort. If I were

destined, indeed, to walk to the scaffold, it seemed that I could

do it with a better grace and a gladder courage now.

THE ELEVENTH HOUR

Castelroux visited me upon the following morning, but he brought no

news that might be accounted encouraging. None of his messengers

were yet returned, nor had any sent word that they were upon the

trail of my followers. My heart sank a little, and such hope as I

still fostered was fast perishing. Indeed, so imminent did my doom

appear and so unavoidable, that later in the day I asked for pen

and paper that I might make an attempt at setting my earthly affairs

to rights. Yet when the writing materials were brought me, I wrote

not. I sat instead with the feathered end of my quill between my

teeth, and thus pondered the matter of the disposal of my Picardy

estates.

Coldly I weighed the wording of the wager and the events that had

transpired, and I came at length to the conclusion that Chatellerault

could not be held to have the least claim upon my lands. That he

had cheated at the very outset, as I have earlier shown, was of less

account than that he had been instrumental in violently hindering me.

I took at last the resolve to indite a full memoir of the transaction,

and to request Castelroux to see that it was delivered to the King

himself. Thus not only would justice be done, but I should - though

tardily - be even with the Count. No doubt he relied upon his power

to make a thorough search for such papers as I might leave, and to

destroy everything that might afford indication of my true identity.

But he had not counted upon the good feeling that had sprung up

betwixt the little Gascon captain and me, nor yet upon my having

contrived to convince the latter that I was, indeed, Bardelys, and

he little dreamt of such a step as I was about to take to ensure his

punishment hereafter.

Resolved at last, I was commencing to write when my attention was

arrested by an unusual sound. It was at first no more than a

murmuring noise, as of at sea breaking upon its shore. Gradually

it grew its volume and assumed the shape of human voices raised in

lusty clamour. Then, above the din of the populace, a gun boomed

out, then another, and another.

I sprang up at that, and, wondering what might be toward, I crossed

to my barred window and stood there listening. I overlooked the

courtyard of the jail, and I could see some commotion below, in

sympathy, as it were, with the greater commotion without.

Presently, as the populace drew nearer, it seemed to me that the

shouting was of acclamation. Next I caught a blare of trumpets,

and, lastly, I was able to distinguish above the noise, which had

now grown to monstrous proportions, the clattering hoofs of some

cavalcade that was riding past the prison doors.

It was borne in upon me that some great personage was arriving in

Toulouse, and my first thought was of the King. At the idea of such

a possibility my brain whirled and I grew dizzy with hope. The

next moment I recalled that but last night Roxalanne had told me

that he was no nearer than Lyons, and so I put the thought from me,

and the hope with it, for, travelling in that leisurely, indolent

fashion that was characteristic of his every action, it would be a

miracle if His Majesty should reach Toulouse before the week was

out, and this but Sunday.

The populace passed on, then seemed to halt, and at last the shouts

died down on the noontide air. I went back to my writing, and to

wait until from my jailer, when next he should chance to appear, I

might learn the meaning of that uproar.

An hour perhaps went by, and I had made some progress with my memoir,

when my door was opened and the cheery voice of Castelroux greeted

me from the threshold.

“Monsieur, I have brought a friend to see you.”

I turned in my chair, and one glance at the gentle, comely face and

the fair hair of the young man standing beside Castelroux was enough

to bring me of a sudden to my feet.

“Mironsac!” I shouted, and sprang towards him with hands outstretched.

But though my joy was great and my surprise profound, greater still

was the bewilderment that in Mironsac’s face I saw depicted.

“Monsieur de Bardelys!” he exclaimed, and a hundred questions were

contained in his astonished eyes.

“Po’ Cap de Dieu!” growled his

Comments (0)