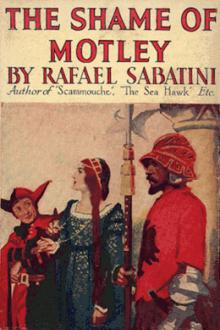

The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

“Where is the Governor of Cesena?” I cried suddenly. Filippo looked at me with quick surprise.

“He departed betimes this morning for his castle. Why do you ask?

I told him why I asked; I told him what I knew of Ramiro’s attentions to Madonna, of the rejection they had suffered, and of the vengeance he had seemed to threaten. Filippo heard me patiently, but when I had done he shook his head.

“Why, all being as you say, should he work so wanton a destruction?” he asked stupidly, as if jealousy were not cause enough to drive an evil man to destroy that which he may not possess. “Nay, nay, your wits are disordered. You remember that he looked at Madonna whilst she drank, and you construe that into a proof that he had poisoned the cup she drank from. But then it is probable that we all looked at her in that same moment.”

“But not with such eyes as his,” I insisted.

“Could he have administered the poison with his own hands?” asked the doctor gravely.

“No,” said I, “that were a difficult matter. But he might have bribed a servant to drop a powder in her wine.”

“Why then,” said he, “it should be an easy thing to find the servant. Do you chance to remember who served the wine?”

“I remember,” answered Filippo readily.

“Let the man be questioned; let him be racked if necessary. Thus shall you probably arrive at a true knowledge; thus discover under whose directions he was working.”

It was the only thing to do, and Filippo sent me about it there and then, telling me the servant in question was a Venetian of the name of Zabatello. If confirmation had been needed that this fellow had been the tool of the poisoner—there was no reason to suppose that he would have done the thing to have served any ends of his own—that confirmation I had upon discovering that Zabatello was fled from Pesaro, leaving no trace behind him.

Men were sent out by the Lord Filippo in every direction to endeavour to find the rogue and bring him back. Whether they caught him or not seemed, after all a little thing to me. She was dead; that was the one all-absorbing, all-effacing fact that took possession of my mind, blotting out all minor matters that might be concerned with it. Even the now assured fact that she had been poisoned was a thing that found little room in my consideration on that day of my burning grief.

She was dead, dead, dead! The hideous phrase boomed again and again through my distracted mind. Compared with that overwhelming catastrophe, what signified to me the how or why or when she had died. She was dead, and the world was empty.

For hours I sat on the rocks, alone by the sea, on that stormy day of December, and I indulged my grief where no prying eyes could witness it, amid the solitude of wild and angry Nature. And the moan and thud with which the great waves hurled themselves against the base of the black rock on which I was perched afforded but a feeble echo of the storm that raged and beat within my desolated soul.

She was dead, dead, dead! The waves seemed to shout it as they leapt up and spattered me with brine; the wind now moaned it piteously, now shrieked it fiercely as it scudded by, wrapping its invisible coils about me, and seeming intent on tearing me from my resting-place.

Towards evening, at last, I rose, and skirting the Castle, I entered the town, dishevelled and bedraggled, yet caring nothing what spectacle I might afford. And presently a grim procession overtook me, and at sight of the black, cowled and visored figures that advanced in the lurid light of their wax torches, I fell on my knees there in the street, and so remained, my knees deep in the mud, my head bowed, until her sainted body had been borne past. None heeded me. They bore her to San Domenico, and thither I followed presently, and in the shadow of one of the pillars of the aisle I crouched whilst the monks chanted their funereal psalms.

The singing ended, the friars departed, and presently those of the Court and the sight-seers from the streets began to leave the church. In an hour I was alone—alone with the beloved dead, and there, on my knees, I stayed, and whether I prayed or blasphemed during that horrid hour, my memory will not let me say.

It may have been towards the third hour of night when at last I staggered up—stiff and cramped from my long kneeling on the cold stone. Slowly, in a half-dazed condition, I move down the aisle and gained the door of the church. I essayed to open it. It resisted my efforts, and then I realised that it was locked for the night.

The appreciation of my position afforded me not the slightest dismay. On the contrary, I think my feelings were rather of relief. I had not known whither I should repair—so distraught was my mood—and now chance had settled the matter for me by decreeing that I should remain.

I turned and slowly I paced back until I stood beside the great black catafalque, at each corner of which a tall wax taper was burning. My footsteps rang with a hollow sound through the vast, gloomy spaces of that cold, empty church; my very breathing seemed to find an echo in it. But these were not things to occupy my mind in such a season, no more than was the icy cold by which I was half-numbed—yet of which I seemed to remain unconscious in the absorbing anguish that possessed me.

Near the foot of the bier there was a bench, and there I sat me down, and resting my elbows on my knees I took my dishevelled head between my frozen hands. My thoughts were all of her whose poor murdered clay was there encased above me. I reviewed, I think, each scene of my life where it had touched on hers; I evoked every word she had addressed to me since first I had met her on the road to Cagli.

And anon my mood changed, and, from cold and frozen that it had been by grief, it grew ablaze with the fire of anger and the lust to wreak vengeance upon him that had brought her to this condition. Let Filippo fear to move without proofs, let him doubt such proofs as I had set before him and deem them overslender to warrant action. Such scruples should not serve to restrain me. I was no lukewarm brother. Here in Pesaro I would remain until her poor body was delivered to the earth, and then I would set out upon a last emprise. Messer Ramiro del’ Orca should account to me for this vile deed.

There in the House of Peace I sat gnawing my hands and maturing my bloody plans whilst the night wore on. Later a still more frenzied mood obsessed me—a burning desire to look again upon the sweet face of her I had loved, the sainted visage of Madonna Paola. What was there to deter me? Who was there to gainsay me?

I stood up and uttered that challenge aloud in my madness. My voice echoed mournfully up the aisles, and the sound of the echo chilled me, yet my purpose gathered strength.

I advanced, and after a moment’s pause, with the silver-broidered hem of the pall in my hands, I suddenly swept off that mantle of black cloth, setting up such a gust of wind as all but quenched the tapers. I caught up the bench on which I had been sitting, and, dragging it forward, I mounted it and stood now with my breast on a level with the coffin-lid. I laid hands on it and found it unfastened. Without thought or care of how I went about the thing, I raised it and let it crash over to the ground. It fell on the stone flags with a noise like that of thunder, which boomed and reverberated along the gloomy vault above.

A figure, all in purest white, lay there under my eyes, the face covered by a veil. With deepest reverence, and a prayer to her sainted soul to forgive the desecration of my loving hands, I tremblingly drew that veil aside. How beautiful she was in the calm peace of death! She lay there like one gently sleeping, the faintest smile upon her lips, and as I looked it seemed hard to believe that she was truly dead. Why, her lips had lost nothing of their colour; they were as rosy red—or nearly so—as ever I had seen them in life. How could this be? The lips of the dead are wont to put on a livid hue. I stared a moment, my reverence and grief almost effaced by the intensity of my wonder. This face, so ivory pale, wore not the ashen aspect of one that would never wake again. There was a warmth about that pallor. And then I caught my nether lip in my teeth until it bled, and it is a miracle that I did not scream, seeing how overwrought was my condition.

For it had seemed to me that the draperies on her bosom had slightly moved, a gentle, almost imperceptible heave as if she breathed. I looked, and there it came again.

God! into what madness was I come that my eyes could so deceive me? It was the draught that stirred the air about the church and blew great shrouds of wax adown the taper’s yellow sides. I manned myself to a more sober mood, and looked again.

And now my doubts were all dispelled. I knew that I had mastered any errant fancy, and that my eyes were grown wise and discriminating, and I knew, too, that she lived. Her bosom slowly rose and fell; the colour of her lips, the hue of her cheeks confirmed the assurance that she breathed. The poison had failed in its work.

I paused a second yet to ponder. That morning her appearance had been such that the physician had been deceived by it, and had pronounced her cold. Yet now there were these signs of life. What could it portend but that the effects of the poison were passing off and that she was recovering?

In the wild madness of joy that sent the blood drumming and beating through my brain, my first impulse was to run for help. Then I bethought me of the closed doors, and I realised that no matter how I shouted none would hear me. I must succour her myself as best I could, and meanwhile she must be protected from the chill air of that December night in that church that was colder than the tomb. I had my cloak, a heavy, serviceable garment; and if more were needed, there was the pall which I had removed, and which lay in a heap about the legs of my bench.

I leaned forward, and passing my hand under her head, I gently raised it. Then slipping it downwards, I thrust my arm after it until I had her round the waist in a firm grip. Thus I raised her from the coffin, and the warmth of her body on my arm, the ready, supple bending of her limbs, were so many added proofs that she was not dead.

Gently and reverently I lifted her in my arms, an intoxication of holy joy pervading me, and the prayers falling faster from my lips than ever they had done since as a lad I had recited them at my mother’s knee. A moment I laid her on the bench, whilst I divested

Comments (0)