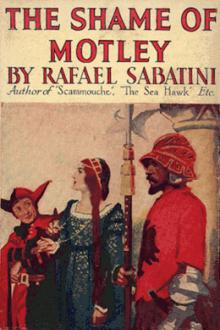

The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley - Rafael Sabatini (the two towers ebook TXT) 📗». Author Rafael Sabatini

I crept round to the front of the altar. At the angle a candle-branch protruded, standing no higher than my head. It held some three or four tapers, and was so placed to enable the priest to read his missal at early Mass on dark winter mornings. I plucked one of the candles from its socket, and hastening down the church, I lighted it from one of the burning tapers of the bier. Screening it with my hand, I retraced my steps and regained the chancel. Then turning to the left, I made for a door that I knew should give access to the sacristy. It yielded to my touch, and I passed down a short stone-flagged passage, and entered the spacious chamber beyond. An oak settle was placed against one wall, and above it hung an enormous, rudely-carved crucifix. Facing it against the other wall loomed a huge piece of furniture, half-cupboard, half-buffet. On a bench in a corner stood a basin and ewer of metal, whilst a few vestments hanging beside these completed the furniture of this austere and white-washed chamber. Setting my candle on the buffet, I opened one of the drawers. It was full of garments of different kinds, among which I noticed several monks’ habits. I rummaged to the bottom only to find some odd pairs of sandals.

Disappointed, I closed the drawer and tried another, with no better fortune. Here were under-vestments of fine linen, newly washed and fragrant with rosemary. I abandoned the drawer and gave my attention to the cupboard above. It was locked, but the key was there. It opened, and my candle reflected a blaze on gold and silver vessels, consecrated chalices; a dazzling monstra, and several richly-carved ciboria of solid gold, set with precious stones. But in a corner I espied a dark-brown, gourd-shaped object. It was a skin of wine, and, with a half-suppressed cry of joy, I seized it. In that instant a piercing scream rang through the stillness of the church, and startled me so that I stood there for some seconds, frozen in horror, a hundred wild conjectures leaping to my mind.

Had Ramiro remained hidden, and was he returned? Did the scream mean that Madonna Paola had been awakened by his rough hands?

A second time it came, and now it seemed to break the hideous spell that its first utterance had cast over me. Dropping the leather bottle, I sped back, down the stone passage to the door that abutted on the chancel.

There, by the high-altar, I saw a form that seemed at first luminous and ghostly, but in which presently I recognised Madonna Paola, the dim rays of the distant tapers finding out the white robe with which her limbs were hung. She was alone, and I knew then that it was but the very natural fear consequent upon awakening in such a place that had provoked the cry I had heard.

“Madonna,” I called, advancing swiftly towards her. “Madonna Paola!” There was a gasp, a moment’s stillness, then—

“Lazzaro?” She cried, questioningly. “What has happened? Why am I here?

I was beside her now, and found her trembling like an aspen.

“Something horrible has happened, Madonna,” I answered. “But it is over now, and the evil is averted.”

“But how came I here?”

“That you shall learn.” I stooped to gather up the cloak which had slipped from her shoulders as she advanced. “Do you wrap this about you,” I urged her, and with my own hands I assisted to enfold her in that mantle. “Are you faint, Madonna?” I asked.

“I scarce know,” she answered in a frightened voice. “There is a black horror upon me. Tell me,” she implored again, “what does it mean?”

I drew her away now, promising to satisfy her in the fullest manner once she were out of these forbidding surroundings. I led her to the sacristy and seating her upon the settle I produced that wine-skin once again.

At first she babbled like a child of not being thirsty; but I was insistent.

“It is no matter of quenching thirst, Madonna,” I told her. “The wine will warm and revive you. Come Madonna mia, drink.”

She obeyed me now, and having got the first gulp down her throat she drank a lusty draught that was not long in bringing a healthier colour to replace the ashen pallor of her cheeks.

“I am so cold, Lazzaro,” she complained.

I turned to the drawer in which I had espied the rough monks’ habits, and pulling one out I held it for her to don. She sat there now, in that garment of coarse black cloth, the cowl flung back upon her shoulder, the fairest postulate that ever entered upon a novitiate.

“You are good to me, Lazzaro,” she murmured plaintively, “and I have used you very ill.” She paused a second, passing her hand across her brow. Then—“What is the hour?” she asked.

It was a question that I left unheeded. I bade her brace herself and have courage for the tale I was to tell. I assured her that the horror of it was all passed and that she had naught to fear. So soon as her natural curiosity should be satisfied it should be hers to return to her brother at the Palace.

“But how came I thence?” she cried. “I must have lain in a swoon, for I remember nothing.” And then her swift mind, leaping to a reasonable conclusion; and assisted, perhaps, by the memory of the shattered catafalque which she had seen—“Did they account me dead, Lazzaro?” she asked of a sudden, her eyes dilating with a curious affright as they were turned upon my own.

“Yes, Madonna,” answered I, “you were accounted dead.” And, with that, I told her the entire story of what had befallen, saving only that I left my own part unmentioned, nor sought to explain my opportune presence in the church. When I spoke of the coming of Ramiro and his knaves she shuddered and closed her eyes in very awe. At length, when I had done, she opened them again, and again she turned them full upon me. Their brightness seemed to increase a moment, and then I saw that she was quietly weeping.

“And you were there to save me, Lazzaro?” she murmured brokenly. “Lazzaro mio, it seems that you are ever at hand when I have need of you. You are indeed my one true friend—the one true friend that never fails me.”

“Are you feeling stronger, Madonna?” I asked abruptly, roughly almost.

“Yes, I am stronger.” She stood up as if to test her strength. “Indeed little ails me saving the horror of this thing. The thought of it seems to turn me sick and dizzy.”

“Sit then and rest,” said I. “Presently, when you are more recovered, we will set out.”

“Whither shall we go?” she asked.

“Why, to the Palace, to your brother.”

“Why, yes,” she answered, as though it were the last suggestion that she had been expecting, “And to-morrow—it will be to-morrow, will it not?— comes the Lord Ignacio to claim his bride. He will owe you no mean thanks, Lazzaro.”

There was a pause. I paced the chamber, a hundred thoughts crowding my mind, but overriding them all the conjecture of how far it might be from matins, and how soon we might be discovered by the monks. Presently she spoke again.

“Lazzaro,” she inquired very gently, “what was it brought you to the church?”

“I came with the others, Madonna, to the burial service,” answered I, and fearing such questions as might follow—questions that I had been dreading ever since I had brought her to the sacristy—“If you are recovered we had best be going,” I told her gruffly.

“Nay, I am not yet enough recovered,” answered she. “And before we go, there are some points in this strange adventure that I would have you make clear to me. Meanwhile, we are very well here. If the good fathers come upon us, what shall it signify?”

I groaned inwardly, and I grew, I think, more afraid than when Ramiro and his men had broken into the church an hour ago.

“What kept you here after all were gone?”

“I remained to pray, Madonna,” I answered brusquely. “Is aught else to be done in a church?”

“To pray for me, Lazzaro?” she asked.

“Assuredly, Madonna.”

“Faithful heart,” she murmured. “And I had used you so cruelly for the deception you practised. But you merited my cruelty, did you not, Lazzaro? Say that you did, else must I perish of remorse.”

“Perhaps I deserved it, Madonna. But perhaps not so much as you bestowed, had you but understood my motives,” I said unguardedly.

“If I had understood your motives?” she mused. “Aye, there is much I do not understand. Even in this night’s transactions there are not wanting things that remain mysterious despite the explanations you have supplied me. Tell me, Lazzaro, what was it led you to suppose that I still lived?

“I did not suppose it,” I blundered like a fool, never seeing whither her question led.

“You did not?” she cried, in deep surprise; and now, when it was too late, I understood. “What was it, then, induced you to lift the coffin-lid?”

“You ask me more than I can tell you,” I answered, almost roughly. “Do you thank God, Madonna, that it was so, and never plague your mind to learn the ‘why’ of it.”

She looked at me with eyes that were singularly luminous.

“But I must know,” she insisted. “Have I not the right? Tell me now: Was it that you wished to see my face again before they gave me over to the grave?”

“Perhaps it was that, Madonna,” I answered in confusion, avoiding her glance. Then—“Shall we be going?” I suggested fiercely. But she never heeded that suggestion.

She spoke as if she had not heard, and the words she uttered seemed to turn me into stone.

“Did you love me then so much, dear Lazzaro?”

I swung round to face her now, and I know that my face was white—whiter than hers had been when I had beheld her in her coffin. My eyes seemed to burn in their sockets as they met hers. A madness overtook me and whelmed my better judgment. I had undergone so much that day through grief, and that night through a hundred emotions, that I was no longer fully master of myself. Her words robbed me, I think, of my last lingering shred of reason.

“Love you, Madonna?” I echoed, in a voice that was as unlike my own as was the mood that then possessed me. “You are the air I breathe, the sun that lights my miserable world. You are dearer to me than honour, sweeter than life. You are the guardian angel of my existence, the saint to whom I have turned morning and evening in my prayers for grace. Do I love you, Madonna—?”

And there I paused. The thought of what I did and what the consequences must be rushed suddenly upon me. I shivered as a man shivers in awaking.

Comments (0)