The Lifeboat - Robert Michael Ballantyne (best short books to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Robert Michael Ballantyne

Book online «The Lifeboat - Robert Michael Ballantyne (best short books to read TXT) 📗». Author Robert Michael Ballantyne

you know where I am and what doing--also to tell you that I have just

heard of the wreck of the ship that conveyed my first letter to you,

which will account for my _apparent_ neglect.

"Gold digging is anything but a paying affair, I find, and it's the

hardest work I've ever had to do. I have only been able to pay my way

up to this time. Everything is fearfully dear. After deducting the

expenses of the last week for cartage, sharpening picks, etcetera, I

and my mate have just realised 15 shillings each; and this is the

first week we have made anything at all beyond what was required for

our living. However, we live and work on in the hope of turning up a

nugget, or finding a rich claim, singing--though we can't exactly

believe--`There's a good time coming.'" Here Bax paused. "I won't

read the next paragraph," said he, with a smile, "because it's about

yourself, Harry, so I'll skip."

Nevertheless, reader, as we wish _you_ to hear that passage, we will make Bax read on.

"My mate, Harry Benton, is an old schoolfellow, whom I met with

accidentally in Melbourne. We joined at once, and have been together

ever since. I hope that nothing may occur to part us. You would like

him, Tommy. You've no idea what a fine, gentle, lion-like fellow he

is, with a face like a true, bold man in expression, and like a

beautiful woman in form. I'm not up to pen-and-ink description,

Tommy, but I think you'll understand me when I say he's got a splendid

figure-head, a strong frame, and a warm heart.

"Poor fellow, he has had much sorrow since he came out here. He is a

widower, and brought out his little daughter with him, an only child,

whose sweet face was once like sunshine in our tent. Not long ago

this pretty flower of the desert sickened, drooped, and died, with her

fair head on her father's bosom. For a long time afterwards Harry was

inconsolable; but he took to reading the Bible, and the effect of that

has been wonderful. We read it regularly every night together, and no

one can tell what comfort we have in it, for I too have had sorrow of

a kind which you could not well understand, unless I were to go into

an elaborate explanation. I believe that both of us can say, in the

words of King David, `It was good for me that I was afflicted.'

"I should like _very_ much that you and he might meet. Perhaps you

may one of these days! But, to go on with my account of our life and

doings here."

(It was at this point that Bax continued to read the letter aloud.)

"The weather is tremendously warm. It is now (10th January) the

height of summer, and the sun is unbearable; quite as hot as in India,

I am told; especially when the hot winds blow. Among other evils, we

are tormented with thousands of fleas. Harry stands them worse than I

do," ("untrue!" interrupted Harry), "but their cousins the flies are,

if possible, even more exasperating. They resemble our own house

flies in appearance--would that they were equally harmless! Myriads

of millions don't express their numbers more than ten expresses the

number of the stars. They are the most persevering brutes you ever

saw. They creep into your eyes, run up your nose, and plunge into

your mouth. Nothing will shake them off, and the mean despicable

creatures take special advantage of us when our hands are occupied in

carrying buckets of gold-dust, or what, alas! ought to be gold-dust,

but isn't! On such occasions we shake our heads, wink our eyes, and

snort and blow at them, but all to no purpose--there they stick and

creep, till we get our hands free to attack them.

"A change must be coming over the weather soon, for while I write, the

wind is blowing like a gale out of a hot oven, and is shaking the

tent, so that I fear it will come down about my ears. It is a curious

fact that these hot winds always blow from the north, which inclines

me to think there must be large sandy deserts in the interior of this

vast continent. We don't feel the heat through the day, except when

we are at the windlass drawing up the pipeclay, or while washing our

`stuff,' for we are generally below ground `driving.' But, although

not so hot as above, it is desperately warm there too, and the air is

bad.

"Our drives are two and a half feet high by about two feet broad at

the floor, from which they widen a little towards the top. As I am

six feet three in my stockings, and Harry is six feet one, besides

being, both of us, broader across the shoulders than most men, you may

fancy that we get into all sorts of shapes while working. All the

`stuff' that we drive out we throw away, except about six inches on

the top where the gold lies, so that the quantity of mullock, as we

call it, or useless material hoisted out is very great. There are

immense heaps of it lying at the mouth of our hole. If we chose to

liken ourselves to gigantic moles, we have reason to be proud of our

mole-hills! All this `stuff' has to be got along the drives, some of

which are twenty-five feet in length. One of us stands at the top,

and hoists the stuff up the shaft in buckets. The other sits and

fills them at the bottom.

"This week we have taken out three cart-loads of washing stuff, which

we fear will produce very little gold. Of course it is quite dark in

the drives, so we use composition candles. Harry drives in one

direction, I in another, and we hammer away from morning till night.

The air is often bad, but not explosive. When the candles burn low

and go out, it is time for us to go out too and get fresh air, for it

makes us blow terribly, and gives us sore eyes. Three-fourths of the

people here are suffering from sore eyes; the disease is worse this

season than it has been in the memory of the oldest diggers.

"We have killed six or seven snakes lately. They are very numerous,

and the only things in the country we are absolutely _afraid_ of! You

have no idea of the sort of dread one feels on coming slap upon one

unexpectedly. Harry put his foot on one yesterday, but got no hurt.

They are not easily seen, and their bite is always fatal.

"From all this you will see that a gold-digger's life is a hard one,

and worse than that, it does not pay well. However, I like it in the

meantime, and having taken it up, I shall certainly give it a fair

trial.

"I wish you were here, Tommy; yet I am glad you are not. To have you

and Guy in the tent would make our party perfect, but it would try

your constitutions I fear, and do you no good mentally, for the

society by which we are surrounded is anything but select.

"But enough of the gold-fields. I have a lot of questions to ask and

messages to send to my old friends and mates at Deal."

At this point the reading of the letter was interrupted by an uproar near the tent. High above the noise the voice of a boy was heard in great indignation.

For a few minutes Bax and his friend did not move; they were too much accustomed to scenes of violence among the miners to think of interfering, unless things became very serious.

"Come, Bill, let him alone," cried a stern voice, "the lad's no thief, as you may see if you look in his face."

"I don't give a straw for looks and faces," retorted Bill, who seemed to have caused the uproar, "the young rascal came peeping into my tent, and that's enough for me."

"What!" cried the boy, in an indignant shout, "may I not search through the tents to find a friend without being abused by every scoundrel who loves his gold so much that he thinks every one who looks at him wants to steal it? Let me go, I say!"

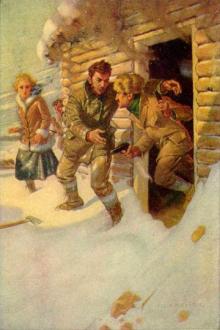

At the first words of this sentence Bax started up with a look of intense surprise. Before it was finished he had seized a thick stick, and rushed from the tent, followed by his mate.

In two seconds they reached the centre of a ring of disputants, in the midst of which a big, coarse-looking miner held by the collar the indignant lad, who proved to be an old and truly unexpected acquaintance.

"Bax!" shouted the boy.

"Tommy Bogey!" exclaimed Bax.

"Off your hands," cried Bax, striding forward.

The miner, who was a powerful man, hesitated. Bax seized him by the neck, and sent him head over heels into his own tent, which stood behind him.

"Serves him right!" cried one of the crowd, who appeared to be delighted with the prospect of a row.

"Hear, hear!" echoed the rest approvingly.

"Can it be _you_, Tommy?" cried Bax, grasping the boy by both arms, and stooping to gaze into his face.

"Found you at last!" shouted Tommy, with his eyes full and his face flushed by conflicting emotions.

"Come into the tent," cried Bax, hastening away and dragging his friend after him.

Tommy did not know whether to laugh or cry. His breast was still heaving with recent indignation, and his heart was bursting with present joy; so he gave utterance to a wild hysterical cheer, and disappeared behind the folds of his friend's tent, amid the cheers and laughter of the miners, who thereafter dispersed quietly to their several places of abode.

"Tommy," said Bax, placing the boy directly in front of him, on a pile of rough coats and blankets, and staring earnestly into his face, "I don't believe it's you! I'm dreaming,

Comments (0)