The Lifeboat - Robert Michael Ballantyne (best short books to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Robert Michael Ballantyne

Book online «The Lifeboat - Robert Michael Ballantyne (best short books to read TXT) 📗». Author Robert Michael Ballantyne

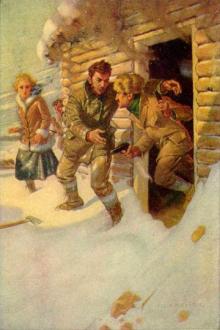

It were vain to attempt to give the broken and disjointed converse that here took place between the two friends. After a time they became more rational and less spasmodic in their talk, and Tommy at last condescended to explain the way in which he had managed to get there.

"But before I begin," said he, "tell me who's your friend?"

He turned as he spoke to Harry, who, seated on a provision cask, with a pleasant smile on his handsome face and a black pipe in his mouth, had been enjoying the scene immensely.

"Ah! true, I forgot; this is my mate, Harry Benton, an old school-fellow. You'll know more of him and like him better in course of time."

"I hope he will," said Harry, extending his hand, which Tommy grasped and shook warmly, "and I hope to become better acquainted with you, Tommy, though in truth you are no stranger to me, for many a night has Bax entertained me in this tent with accounts of your doings and his own, both by land and sea. Now go on, my boy, and explain the mystery of your sudden appearance here."

"The prime cause of my appearance is the faithlessness of Bax," said Tommy. "Why did you not write to me?"

When it was explained that Bax had written by a vessel which was wrecked, the boy was mollified; and when the letter which had just been written was handed to him, he confessed that he had judged his old friend hastily. Thereafter he related succinctly his adventures in the "Butterfly" up to the point where we left him sound asleep in the skipper's berth.

"How long I slept," said Tommy, continuing the narrative, "I am not quite sure; but it must have been a longish time, for it was somewhere in a Tuesday when I lay down, and it was well into a Thursday when I got up, or rather was knocked up by the bow of a thousand-ton ship! It was a calm evening, with just a gentle breeze blowin' at the time, and a little hazy. The look out in the ship did not see the schooner until he was close on her; then he yelled `hard-a-lee!' so I was told, for I didn't hear it, bein', as I said, sound asleep. But I heard and felt what followed plain enough. There came a crash like thunder. I was pitched head-foremost out o' the berth, and would certainly have got my neck broken, but for the flimsy table in the cabin, which gave way and went to pieces under me, and thus broke my fall. I got on my legs, and shot up the companion like a rocket. I was confused enough, as you may suppose, but I must have guessed at once what was wrong--perhaps the rush of water told it me--for I leaped instantly over the side into the sea to avoid being sucked down by the sinking vessel. Down it went sure enough, and I was so near it that in spite of my struggles I was carried down a long way, and all but choked. However, up I came again like a cork. You always said I was light-headed, Bax, and I do believe that was the reason I came up so soon!

"Well, I swam about for ten minutes or so, when a boat rowed up to the place. It had been lowered by the ship that ran me down. I was picked up and taken aboard, and found that she was bound for Australia!

"Ha! that just suited you, I fancy," said Bax.

"Of course it did, but that's not all. Who d'ye think the ship belonged to? You'll never guess;--to your old employers, Denham, Crumps, and Company! She is named the `Trident,' after the one that was lost, and old Denham insisted on her sailing on a Friday. The sailors said she would be sure to go to the bottom, but they were wrong, for we all got safe to Melbourne, after a very good voyage.

"Well, I've little more to tell now. On reaching Melbourne I landed--"

"Without a sixpence in your pocket?" asked Bax.

"By no means," said Tommy, "I had five golden sovereigns sewed up in the waist-band of my trousers, not to mention a silver watch like a saucepan given to me by old Jeph at parting, and a brass ring that I got from Bluenose! But it's wonderful how fast this melted away in Melbourne. It was half gone before I succeeded in finding out what part of the country you had gone to. The rest of it I paid to a party of miners, who chanced to be coming here, for leave to travel and feed with them. They left me in the lurch, however, about two days' walk from this place; relieving me of the watch at parting, but permitting me to keep the ring as a memorial of the pleasant journey we had had together! Then the rascals left me with provisions sufficient for one meal. So I came on alone; and now present myself to you half-starved and a beggar!"

"Here is material to appease your hunger, lad," said Harry Benton, with a laugh, as he tossed a mass of flour cake, known among diggers as "damper," towards the boy.

"And here," added Bax, pitching a small bag of gold-dust into his lap, "is material to deliver you from beggary, at least for the present. As for the future, Tommy, your own stout arms must do the rest. You'll live in our tent, and we'll make a gold-digger of you in a couple of days. I could have wished you better fortune, lad, but as you have managed to make your way to this out-o'-the-way place, I suppose you'll want to remain."

"I believe you, my boy!" said Tommy, with his mouth full of damper.

So Tommy Bogey remained with his friends at the Kangaroo Flats, and dug for gold.

For several years they stuck to the laborious work, during which time they dug up just enough to keep themselves in food and clothing. They were unlucky diggers. Indeed, this might have been said of most of the diggers around them. Those who made fortunes, by happening to find rich spots of ground, were very few compared with the host of those who came with light hearts, hoping for heavy pockets, and went away with heavy hearts and light pockets.

We shall not follow the fortunes of those three during their long period of exile. The curtain was lifted in order that the Reader might take a glance at them in the far-off land. They are a pleasant trio to look upon. They do not thirst feverishly for the precious metal as many do. Their nightly reading of the Word saves them from that. Nevertheless, they work hard, earn little, and sleep soundly. As we drop the curtain, they are still toiling and moiling, patiently, heartily, and hopefully, for gold.

CHAPTER NINETEEN.

DENHAM LONGS FOR FRESH AIR, AND FINDS IT.

There came a day, at last, in which foul air and confinement, and money-making, began to tell on the constitution of Mr Denham; to disagree with him, in fact. The rats began to miss him, occasionally, from Redwharf Lane, at the wonted hour, and, no doubt, gossiped a good deal on the subject over their evening meals, after the labours and depredations of the day were ended!

They observed too (supposing them to have been capable of observation), that when Mr Denham did come to his office, he came with a pale face and an enfeebled step; also with a thick shawl wrapped round his neck. These peculiarities were so far taken advantage of by the rats that they ceased to fly with their wonted precipitancy when his step was heard, and in course of time they did not even dive into their holes as in former days, but sat close to them and waited until the merchant had passed, knowing well that he was not capable of running at them. One large young rat in particular--quite a rattling blade in his way--at length became so bold that he stood his ground one forenoon, and deliberately stared at Mr Denham as he tottered up to the office-door.

We notice this fact because it occurred on the memorable day when Mr Denham admitted to himself that he was breaking down, and that something must be done to set him up again. He thought, as he sat at his desk, leaning his head on his right hand, that sea-air might do him good, and the idea of a visit to his sister at Deal flitted across his mind; but, remembering that he had for many years treated that sister with frigid indifference, and that he had dismissed her son Guy harshly and without sufficient reason from his employment a few years ago, he came to the conclusion that Deal was not a suitable locality. Then he thought of Margate and Ramsgate, and even ventured to contemplate the Scotch Highlands, but his energy being exhausted by illness, he could not make up his mind, so he sighed and felt supremely wretched.

Had there been any one at his elbow, to suggest a plan of some sort, and urge him to carry it out, he would have felt relieved and grateful. But plans for our good are usually suggested and urged by those who love us, and Denham, being a bachelor and a misanthrope, happened to have no one to love him. He was a very rich man--very rich indeed; and would have given a great deal of gold at that moment for a very small quantity of love, but love is not a marketable commodity. Denham knew that and sighed again. He felt that in reference to this thing he was a beggar, and, for the first time in his life, experienced something of a beggar's despair.

While he sat thus, musing bitterly, there came a tap at the door.

"Come in."

The tapper came in, and presented to the astonished gaze of Mr Denham the handsome face and figure of Guy Foster.

"I trust you will forgive my intrusion, uncle," said Guy in apologetic tones, as he advanced with a rather hesitating step, "but I am the bearer of a message from my mother."

Denham had looked up in surprise, and with a dash of sternness, but the expression passed into one of sadness mingled with suffering. He pointed to a chair and said curtly, "Sit down," as he replaced his forehead on his hand, and partially concealed his haggard face.

"I am deeply grieved, dear uncle," continued Guy, "to see you looking so very ill. I do sincerely hope--"

"Your message?" interrupted Denham.

"My mother having heard frequently of late that you are far from well, and conceiving that the fresh air of Deal might do you good, has sent me to ask you to be our guest for a time. It would afford us very great pleasure, I assure you, uncle."

Guy paused here, but Mr Denham did not speak. The kindness of the unexpected and certainly unmerited invitation, put, as it was, in tones which expressed great earnestness and regard, took him aback. He felt ill at ease, and his wonted self-possession forsook him.

Comments (0)