The Gun-Brand - James B. Hendryx (ap literature book list txt) 📗

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Gun-Brand - James B. Hendryx (ap literature book list txt) 📗». Author James B. Hendryx

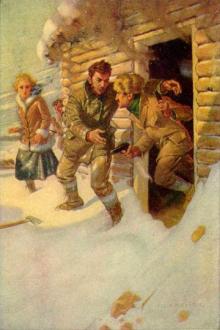

But few seconds had elapsed since Chloe felt the hand of Vermilion close about her wrist—tense, frenzied seconds, to the mind of the girl, who gazed in bewilderment upon the bodies of the two dead men which lay almost touching each other.

The man who had ordered Vermilion to release her, and who had fired the shot that had killed him, stood calmly watching four lithe-bodied canoemen securely bind the arms of the two scowmen who had attacked Big Lena.

So sudden had been the transition from terror to relief in her heart that the scene held nothing of repugnance to the girl, who was conscious only of a feeling of peace and security. She even smiled into the eyes of her deliverer, who had turned his attention from his canoemen and stood before her, his soft-brimmed Stetson in his hand.

"Oh! I—I thank you!" exclaimed the girl, at a loss for words.

The man bowed low. "It is nothing. I am glad to have been of some slight service." Something in the tone of the well-modulated voice, the correct speech, the courtly manner, thrilled the girl strangely. It was all so unexpected—so out of place, here in the wild. She felt the warm colour mount to her face.

"Who are you?" she asked abruptly.

"I am Pierre Lapierre," answered the man in the same low voice.

In spite of herself, Chloe started slightly, and instantly she knew that the man had noticed. He smiled, with just an appreciable tightening at the corners of the mouth, and his eyes narrowed almost imperceptibly. He continued:

"And now, Miss Elliston, if you will retire to your tent for a few moments, I will have these removed." He indicated the bodies. "You see, I know your name. The good Chenoine told me. He it was who warned me of Vermilion's plot in time for me to frustrate it. Of course, I should have rescued you later. I hold myself responsible for the safe conduct of all who travel in my scows. But it would have been at the expense of much time and labour, and, very possibly, of human life as well—an incident regrettable always, but not always avoidable."

Chloe nodded, and, with her thoughts in a whirl of confusion, turned and entered her tent, where Harriet Penny lay sobbing hysterically, with her blankets drawn over her head.

A half-hour later, when Chloe again ventured from the tent, all evidence of the struggle had disappeared. The bodies of the two dead men had been removed, and the canoemen were busily engaged in gathering together and restoring the freight pieces that had been ripped open by the scowmen.

Lapierre advanced to meet her, his carefully creased Stetson in hand.

"I have sent word for the other scows to come on at once, and in the meantime, while my men attend to the freight, may we not talk?"

Chloe assented, and the two seated themselves upon a log. It was then, for the first time that the girl noticed that one side of Lapierre's face—the side he had managed to keep turned from her—was battered and disfigured by some recent misadventure. Noticed, too, the really fine features of him—the dark, deep-set eyes that seemed to smoulder in their depths, the thin, aquiline nose, the shapely lips, the clean-cut lines of cheek and jaw.

"You have been hurt!" she cried. "You have met with an accident!"

The man smiled, a smile in which cynicism blended with amusement.

"Hardly an accident, I think, Miss Elliston, and, in any event, of small consequence." He shrugged a dismissal of the subject, and his voice assumed a light gaiety of tone.

"May we not become better acquainted, we two, who meet in this far place, where travellers are few and worth the knowing?" There was no cynicism in his smile now, and without waiting for a reply he continued: "My name you already know. I have only to add that I am an adventurer in the wilds—explorer of hinterlands, free-trader, freighter, sometime prospector—casual cavalier." He rose, swept the Stetson from his head, and bowed with mock solemnity.

"And now, fair lady, may I presume to inquire your mission in this land of magnificent wastes?" Chloe's laughter was genuine as it was spontaneous.

Lapierre's light banter acted as a tonic to the girl's nerves, harassed as they were by a month's travel through the fly-bitten wilderness. More—he interested her. He was different. As different from the half-breeds and Indian canoemen with whom she had been thrown as his speech was from the throaty guttural by means of which they exchanged their primitive ideas.

"Pray pause, Sir Cavalier," she smiled, falling easily into the gaiety of the man's mood. "I have ventured into your wilderness upon a most unpoetic mission. Merely the establishment of a school for the education and betterment of the Indians of the North."

A moment of silence followed the girl's words—a moment in which she was sure a hard, hostile gleam leaped into the man's eyes. A trick of fancy doubtless, she thought, for the next instant it had vanished. When he spoke, his air of light raillery was gone, but his lips smiled—a smile that seemed to the girl a trifle forced.

"Ah, yes, Miss Elliston. May I ask at whose instigation this school is to be established—and where?" He was not looking at her now, his eyes sought the river, and his face showed only a rather finely moulded chin, smooth-shaven—and the lips, with their smile that almost sneered.

Instantly Chloe felt that a barrier had sprung up between herself and this mysterious stranger who had appeared so opportunely out of the Northern bush. Who was he? What was the meaning of the old factor's whispered warning? And why should the mention of her school awake disapproval, or arouse his antagonism? Vaguely she realized that the sudden change in this man's attitude hurt. The displeasure, and opposition, and ridicule of her own people, and the surly indifference of the rivermen, she had overridden or ignored. This man she could not ignore. Like herself, he was an adventurer of untrodden ways. A man of fancy, of education and light-hearted raillery, and yet, a strong man, withal—a man of moment, evidently.

She remembered the sharp, quick words of authority—the words that caused the villainous Vermilion to whirl with a snarl of fear. Remembered also, the swift sure shot that had ended Vermilion's career, his absolute mastery of the situation, his lack of excitement or braggadocio, and the expressed regret over the necessity for killing the man. Remembered the abject terror in the eyes of those who fled into the bush at his appearance, and the servility of the canoemen.

As she glanced into the half-turned face of the man, Chloe saw that the sneering smile had faded from the thin lips as he waited her answer.

"At my own instigation." There was an underlying hardness of defiance in her words, and the firm, sun-reddened chin unconsciously thrust forward beneath the encircling mosquito net. She paused, but the man, expressionless, continued to gaze out over the surface of the river.

"I do not know exactly where," she continued, "but it will be somewhere. Wherever it will do the most good. Upon the bank of some river, or lake, perhaps, where the people of the wilderness may come and receive that which is theirs of right——"

"Theirs of right?" The man looked into her face, and Chloe saw that the thin lips again smiled—this time with a quizzical smile that hinted at tolerant amusement. The smile stung.

"Yes, theirs of right!" she flashed. "The education that was freely offered to me, and to you—and of which we availed ourselves."

For a long time the man continued to gaze in silence, and, when at length he spoke, it was to ask an entirely irrelevant question.

"Miss Elliston, you have heard my name before?"

The question came as a surprise, and for a moment Chloe hesitated. Then frankly, and looking straight into his eyes she answered:

"Yes, I have."

The man nodded, "I knew you had." He turned his injured eye quickly from the dazzle of the sunlight that flashed from the surface of the river, and Chloe saw that it was discoloured and bloodshot. She arose, and stepping to his side laid her hand upon his arm.

"You are hurt," she said earnestly, "your eye gives you pain."

Beneath her fingers the girl felt the play of strong muscles as the arm pressed against her hand. Their eyes met, and her heart quickened with a strange new thrill. Hastily she averted her glance and then—— The man's arm suddenly was withdrawn and Chloe saw that his fist had clinched. With a rush the words brought back to him the scene in the trading-room of the post at Fort Rae. The low, log-room, piled high with the goods of barter. The great cannon stove. The two groups of dark-visaged Indians—his own Chippewayans, and MacNair's Yellow Knives, who stared in stolid indifference. The trembling, excited clerk. The grim chief trader, and the stern-faced factor who watched with approving eyes while two men fought in the wide cleared space between the rough counter and the high-piled bales of woollens and strouds.

Chloe Elliston drew back aghast. The thin lips of the man had twisted into a snarl of rage, and a living, bestial hate seemed fairly to blaze from the smouldering eyes, as Lapierre's thoughts dwelt upon the closing moments of that fight, when he felt himself giving ground before the hammering, smashing blows of Bob MacNair's big fists. Felt the tightening of the huge arms like steel bands about his body when he rushed to a clinch—bands that crushed and burned so that each sobbing breath seemed a blade, white-hot from the furnace, stabbing and searing into his tortured lungs. Felt the vital force and strength of him ebb and weaken so that the lean, slender fingers that groped for MacNair's throat closed feebly and dropped limp to dangle impotently from his nerveless arms. Felt the sudden release of the torturing bands of steel, the life-giving inrush of cool air, the dull pain as his dizzy body rocked to the shock of a crashing blow upon the jaw, the blazing flash of the blow that closed his eye, and, then—more soul-searing, and of deeper hurt than the blows that battered and marred—the feel of thick fingers twisted into the collar of his soft shirt. Felt himself shaken with an incredible ferocity that whipped his ankles against floor and counter edge. And, the crowning indignity of all—felt himself dragged like a flayed carcass the full length of the room, out of the door, and jerked to his feet upon the verge of the steep descent to the lake. Felt the propelling impact of the heavy boot that sent him crashing headlong into the underbrush through which he rolled and tumbled like a mealbag, to bring up suddenly in the cold water.

The whole scene passed through his brain as dreams flash—almost within the batting of an eye. Half-consciously, he saw the girl's sudden start, and the look of alarm upon her face as she drew back from the glare of his hate-flashing eyes and the bestial snarl of his lips. With an effort he composed himself:

"Pardon, Miss Elliston, I have frightened you with an uncouth show of savagery. It is a rough, hard country—this land of the wolf and the caribou. Primal instincts and brutish passions here are unrestrained—a fact responsible for my present battered appearance. For, as I said, it was no accident that marred me

Comments (0)