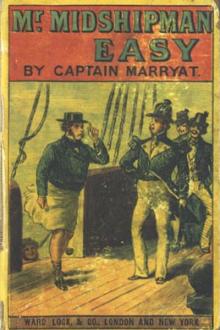

Mr. Midshipman Easy - Frederick Marryat (best ereader for students TXT) 📗

- Author: Frederick Marryat

- Performer: -

Book online «Mr. Midshipman Easy - Frederick Marryat (best ereader for students TXT) 📗». Author Frederick Marryat

“MY DEAR Boy,-Although not a correspondent of yours, I take the right of having watched you through all your childhood, and from a knowledge of your disposition, to write you a few lines. That you have, by this time, discarded your father’s foolish, nonsensical philosophy, I am very sure. It was I who advised your going away for that purpose, and I am sure, that, as a young man of sense, and the heir to a large property, you will before this have seen the fallacy of your father’s doctrines. Your father tells me that he has requested you to come home, and allow me to add any weight I may have with you in persuading you to do the same. It is fortunate for you that the estate is entailed, or you might soon be a beggar, for there is no saying what debts he might, in his madness, be guilty of. He has already been dismissed from the magistracy by the lord-lieutenant, in consequence of his haranguing the discontented peasantry, and I may say, exciting them to acts of violence and insubordination. He has been seen dancing and hurrahing round a stack fired by an incendiary. He has turned away his keepers, and allowed all poachers to go over the manor. In short, he is not in his senses; and, although I am far from advising coercive measures, I do consider that it is absolutely necessary that you should immediately return home, and look after what will one day be your property. You have no occasion to follow the profession, with eight thousand pounds per annum. You have distinguished yourself,-now make room for those who require it for their subsistence. God bless you. I shall soon hope to shake hands with you. “Yours most truly, “G. MIDDLETON.”

There was matter for deep reflection in these two letters, and Jack never felt before how much his father had been in the wrong. That he had gradually been weaned from his ideas was true, but still he had, to a certain degree, clung to them, as we do to a habit; but now he felt that his eyes were opened; the silly, almost unfeeling letter of his father upon the occasion of his mother’s death, opened his eyes. For a long while Jack was in a melancholy meditation, and then casting his eyes upon his watch, he perceived that it was almost dinnertime. That he could eat his dinner was certain, and he scorned to pretend to feel what he did not. He therefore dressed himself and went down, grave, it is true, but not in tears. He spoke little at dinner, and retired as soon as it was over, presenting his two letters to the Governor, and asking his advice for the next morning. Gascoigne followed him, and to him he confided his trouble; and Ned, finding that Jack was very low-spirited, consoled him to the best of his power, and brought a bottle of wine which he procured from the butler. Before they returned to bed, Jack had given his ideas to his friend, which were approved of, and wishing him a goodnight, he threw himself into bed, and was soon fast asleep.

“One thing is certain, my good fellow,” observed the Governor to our hero, as he gave him back his letters at the breakfast table the next morning; “that your father is as mad as a March hare. I agree with that doctor, who appears a sensible man, that you had better go home immediately.”

“And leave the service altogether, sir?” replied Jack.

“Why, I must say, that I do not think you exactly fitted for it. I shall be sorry to lose you, as you have a wonderful talent for adventure, and I shall have no more yams to hear when you return; but, if I understand right from Captain Wilson, you were brought into the profession because he thought that the service might be of use in eradicating false notions, rather than from any intention or necessity of your following it up as a profession.”

“I suspect that was the case, sir,” replied Jack; “as, for my own part, I hardly know why I entered it.”

“To find a mare’s nest, my lad; I’ve heard all about it; but never mind that: the question is now about your leaving it, to look after your own property, and I think I may venture to say, that I can arrange all that matter at once, without referring to Admiral or captain. I will be responsible for you, and you may go home in the packet, which sails on Wednesday for England.”

“Thank you, Sir Thomas, I am much obliged to you,” replied Jack.

“You, Mr Gascoigne, I shall, of course, send out by the first opportunity to rejoin your ship.”

“Thank you, Sir Thomas, I am much obliged to you,” replied Gascoigne, making a bow.

“You’ll break no more arms, if you please, sir,” continued the Governor; “a man in love may have some excuse in breaking his leg, but you had none.”

“I beg your pardon, sir; if Mr Easy was warranted in breaking his leg out of love, I submit that I could do no less than break my arm out of friendship.”

“Hold your tongue, sir, or I’ll break your head from the very opposite feeling,” replied the Governor, good-humouredly. “But observe, young man, I shall keep this affair secret, as in honour bound; but let me advise you, as you have only your profession to look to, to follow it up steadily. It is high time that you and Mr Easy were separated. He is independent of the service, and you are not. A young man possessing such ample means will never be fitted for the duties of a junior officer. He can do no good for himself, and is certain to do much harm to others: a continuance of his friendship would probably end in your ruin, Mr Gascoigne. You must be aware, that if the greatest indulgence had not been shown to Mr Easy by his captain and first lieutenant, he never could have remained in the service so long as he has done.”

As the Governor made the last remark in rather a severe tone, our two midshipmen were silent for a minute. At last Jack observed, very quietly,-

“And yet, sir, I think, considering all, I have behaved pretty well.”

“You have behaved very well, my good lad, on all occasions in which your courage and conduct, as an officer, have been called forth. I admit it; and had you been sent to sea with a mind properly regulated, and without such an unlimited command of money, I have no doubt but that you would have proved an ornament to the service. Even now I think you would, if you were to remain in the service under proper guidance and necessary restrictions, for you have, at least, learnt to obey, which is absolutely necessary before you are fit to command. But recollect, what your conduct would have brought upon you, if you had not been under the parental care of Captain Wilson. But let us say no more about that: a midshipman with the prospect of eight thousand pounds a-year is an anomaly which the service cannot admit, especially when that midshipman is resolved to take to himself a wife.”

“I hope that you approve of that step, sir.”

“That entirely depends upon the merit of the party, which I know nothing of, except that she has a pretty face, and is of one of the best Sicilian families. I think the difference of religion a ground of objection.”

“We will argue that point, sir,” replied Jack.

“Perhaps it will be the cause of more argument than you think for, Mr Easy; but every man makes his own bed, and as he makes it, so must he lie down in it.”

“What am I to do about Mesty, sir? I cannot bear the idea of parting with him.”

“I am afraid that you must; I cannot well interfere there.”

“He is of little use to the service, sir; he has been sent to sick quarters as my servant: if he may be permitted to go home with me, I will procure his discharge as soon as I arrive, and send him on board the guard-ship till I obtain it.”

“I think that, on the whole, he is as well out of the service as in it, and therefore I will, on consideration, take upon myself the responsibility, provided you do as you say.”

The conversation was here ended, as the Governor had business to attend to, and Jack and Gascoigne went to their rooms to make their arrangements.

“The Governor is right,” observed Gascoigne; “it is better that we part, Jack. You have half unfitted me for the service already; I have a disgust of the midshipmen’s berth; the very smell of pitch and tar has become odious to me. This is all wrong; I must forget you and all our pleasant cruises on shore, and once more swelter in my greasy Jacket. When I think that, if our pretended accidents were discovered, I should be dismissed the service, and the misery which that would cause to my poor father, I tremble at my escape. The Governor is right, Jack; we must part, but I hope you never will forget me.”

“My hand upon it, Ned. Command my interest, if ever I have any-my money-what I have, and the house, whether it belongs to me or my father-as far as you are concerned at least, I adhere to my notions of perfect equality.”

“And abjure them, I trust, Jack, as a universal principle.”

“I admit, as the Governor asserts, that my father is as mad as a March hare.”

“That is sufficient; you don’t know how glad it makes me to hear you say that.”

The two friends were inseparable during the short time that they remained together. They talked over their future prospects, their hopes and anticipations, and when the conversation flagged, Gascoigne brought up the name of Agnes.

Mesty’s delight at leaving the service, and going home with his patron was indescribable. He laid out a portion of his gold in a suit of plain clothes, white linen shirts, and in every respect the wardrobe of a man of fashion; in fact, he was now a complete gentleman’s gentleman; was very particular in frizzing his woolly hair-wore a white neck-cloth, gloves, and cane. Every one felt inclined to laugh when he made his appearance; but there was something in Mesty’s look, which, at all events, prevented their doing so before his face. The day for sailing arrived. Jack took leave of the Governor, thanking him for his great kindness, and stating his intention of taking Malta in his way out to Palermo in a month or two. Gascoigne went on board with him, and did not go down the vessel’s side till it was more than a mile clear of the harbour.

Mr Easy’s wonderful invention fully explained by himself-much to the satisfaction of our hero, and it is to be presumed to that also of the reader.

AT LAST the packet anchored in Falmouth Roads. Jack, accompanied by Mesty, was soon on shore with his luggage, threw himself into the mail, arrived in London, and, waiting there two or three days, to obtain what he considered necessary from a fashionable tailor, ordered a chaise to Forest Hill. He had not written to his father to announce his arrival, and it was late in the morning when the chaise drew up at his father’s door.

Comments (0)