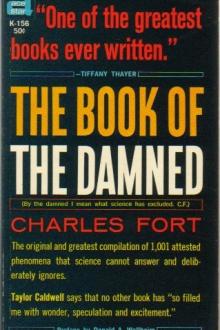

The Book of the Damned - Charles Fort (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned - Charles Fort (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗». Author Charles Fort

We weakly drop a hint to the aeronauts.

In the Scientific American, 33-197, there is an account of some hay that fell from the sky. From the circumstances we incline to accept that this hay went up, in a whirlwind, from this earth, in the first place, reached the Super-Sargasso Sea, and remained there a long time before falling. An interesting point in this expression is the usual attribution to a local and coinciding whirlwind, and identification of it—and then data that make that local whirlwind unacceptable—

That, upon July 27, 1875, small masses of damp hay had fallen at Monkstown, Ireland. In the Dublin Daily Express, Dr. J.W. Moore had explained: he had found a nearby whirlwind, to the south of Monkstown, that coincided. But, according to the Scientific American, a similar fall had occurred near Wrexham, England, two days before.

In November, 1918, I made some studies upon light objects thrown into the air. Armistice-day. I suppose I should have been more emotionally occupied, but I made notes upon torn-up papers thrown high in the air from windows of office buildings. Scraps of paper did stay together for a while. Several minutes, sometimes.

Cosmos, 3-4-574:

That, upon the 10th of April, 1869, at Autriche (Indre-et-Loire) a great number of oak leaves—enormous segregation of them—fell from the sky. Very calm day. So little wind that the leaves fell almost vertically. Fall lasted about ten minutes.

Flammarion, in The Atmosphere, p. 412, tells this story.

He has to find a storm.

He does find a squall—but it had occurred upon April 3rd.

Flammarion's two incredibilities are—that leaves could remain a week in the air: that they could stay together a week in the air.

Think of some of your own observations upon papers thrown from an aeroplane.

Our one incredibility:

That these leaves had been whirled up six months before, when they were common on the ground, and had been sustained, of course not in the air, but in a region gravitationally inert; and had been precipitated by the disturbances of April rains.

I have no records of leaves that have so fallen from the sky in October or November, the season when one might expect dead leaves to be raised from one place and precipitated somewhere else. I emphasize that this occurred in April.

La Nature, 1889-2-94:

That, upon April 19, 1889, dried leaves, of different species, oak, elm, etc., fell from the sky. This day, too, was a calm day. The fall was tremendous. The leaves were seen to fall fifteen minutes, but, judging from the quantity on the ground, it is the writer's opinion that they had already been falling half an hour. I think that the geyser of corpses that sprang from Riobamba toward the sky must have been an interesting sight. If I were a painter, I'd like that subject. But this cataract of dried leaves, too, is a study in the rhythms of the dead. In this datum, the point most agreeable to us is the very point that the writer in La Nature emphasizes. Windlessness. He says that the surface of the Loire was "absolutely smooth." The river was strewn with leaves as far as he could see.

L'Astronomie, 1894-194:

That, upon the 7th of April, 1894, dried leaves fell at Clairvaux and Outre-Aube, France. The fall is described as prodigious. Half an hour. Then, upon the 11th, a fall of dried leaves occurred at Pontcarré.

It is in this recurrence that we found some of our opposition to the conventional explanation. The Editor (Flammarion) explains. He says that the leaves had been caught up in a cyclone which had expended its force; that the heavier leaves had fallen first. We think that that was all right for 1894, and that it was quite good enough for 1894. But, in these more exacting days, we want to know how wind-power insufficient to hold some leaves in the air could sustain others four days.

The factors in this expression are unseasonableness, not for dried leaves, but for prodigious numbers of dried leaves; direct fall, windlessness, month of April, and localization in France. The factor of localization is interesting. Not a note have I upon fall of leaves from the sky, except these notes. Were the conventional explanation, or "old correlate" acceptable, it would seem that similar occurrences in other regions should be as frequent as in France. The indication is that there may be quasi-permanent undulations in the Super-Sargasso Sea, or a pronounced inclination toward France—

Inspiration:

That there may be a nearby world complementary to this world, where autumn occurs at the time that is springtime here.

Let some disciple have that.

But there may be a dip toward France, so that leaves that are borne high there, are more likely to be held in suspension than highflying leaves elsewhere. Some other time I shall take up Super-geography, and be guilty of charts. I think, now, that the Super-Sargasso Sea is an oblique belt, with changing ramifications, over Great Britain, France, Italy, and on to India. Relatively to the United States I am not very clear, but think especially of the Southern States.

The preponderance of our data indicates frigid regions aloft. Nevertheless such phenomena as putrefaction have occurred often enough to make super-tropical regions, also, acceptable. We shall have one more datum upon the Super-Sargasso Sea. It seems to me that, by this time, our requirements of support and reinforcement and agreement have been quite as rigorous for acceptance as ever for belief: at least for full acceptance. By virtue of mere acceptance, we may, in some later book, deny the Super-Sargasso Sea, and find that our data relate to some other complementary world instead—or the moon—and have abundant data for accepting that the moon is not more than twenty or thirty miles away. However, the Super-Sargasso Sea functions very well as a nucleus around which to gather data that oppose Exclusionism. That is our main motive: to oppose Exclusionism.

Or our agreement with cosmic processes. The climax of our general expression upon the Super-Sargasso Sea. Coincidentally appears something else that may overthrow it later.

Notes and Queries, 8-12-228:

That in the province of Macerata, Italy (summer of 1897?) an immense number of small, blood-colored clouds covered the sky. About an hour later a storm broke, and myriad seeds fell to the ground. It is said that they were identified as products of a tree found only in Central Africa and the Antilles.

If—in terms of conventional reasoning—these seeds had been high in the air, they had been in a cold region. But it is our acceptance that these seeds had, for a considerable time, been in a warm region, and for a time longer than is attributable to suspension by wind-power:

"It is said that a great number of the seeds were in the first stage of germination."

20The New Dominant.

Inclusionism.

In it we have a pseudo-standard.

We have a datum, and we give it an interpretation, in accordance with our pseudo-standard. At present we have not the delusions of Absolutism that may have translated some of the positivists of the nineteenth century to heaven. We are Intermediatists—but feel a lurking suspicion that we may some day solidify and dogmatize and illiberalize into higher positivists. At present we do not ask whether something be reasonable or preposterous, because we recognize that by reasonableness and preposterousness are meant agreement and disagreement with a standard—which must be a delusion—though not absolutely, of course—and must some day be displaced by a more advanced quasi-delusion. Scientists in the past have taken the positivist attitude—is this or that reasonable or unreasonable? Analyze them and we find that they meant relatively to a standard, such as Newtonism, Daltonism, Darwinism, or Lyellism. But they have written and spoken and thought as if they could mean real reasonableness and real unreasonableness.

So our pseudo-standard is Inclusionism, and, if a datum be a correlate to a more widely inclusive outlook as to this earth and its externality and relations with externality, its harmony with Inclusionism admits it. Such was the process, and such was the requirement for admission in the days of the Old Dominant: our difference is in underlying Intermediatism, or consciousness that though we're more nearly real, we and our standards are only quasi—

Or that all things—in our intermediate state—are phantoms in a super-mind in a dreaming state—but striving to awaken to realness.

Though in some respects our own Intermediatism is unsatisfactory, our underlying feeling is—

That in a dreaming mind awakening is accelerated—if phantoms in that mind know that they're only phantoms in a dream. Of course, they too are quasi, or—but in a relative sense—they have an essence of what is called realness. They are derived from experience or from senes-relations, even though grotesque distortions. It seems acceptable that a table that is seen when one is awake is more nearly real than a dreamed table, which, with fifteen or twenty legs, chases one.

So now, in the twentieth century, with a change of terms, and a change in underlying consciousness, our attitude toward the New Dominant is the attitude of the scientists of the nineteenth century to the Old Dominant. We do not insist that our data and interpretations shall be as shocking, grotesque, evil, ridiculous, childish, insincere, laughable, ignorant to nineteenth-centuryites as were their data and interpretations to the medieval-minded. We ask only whether data and interpretations correlate. If they do, they are acceptable, perhaps only for a short time, or as nuclei, or scaffolding, or preliminary sketches, or as gropings and tentativenesses. Later, of course, when we cool off and harden and radiate into space most of our present mobility, which expresses in modesty and plasticity, we shall acknowledge no scaffoldings, gropings or tentativenesses, but think we utter absolute facts. A point in Intermediatism here is opposed to most current speculations upon Development. Usually one thinks of the spiritual as higher than the material, but, in our acceptance, quasi-existence is a means by which the absolutely immaterial materializes absolutely, and, being intermediate, is a state in which nothing is finally either immaterial or material, all objects, substances, thoughts, occupying some grade of approximation one way or the other. Final solidification of the ethereal is, to us, the goal of cosmic ambition. Positivism is Puritanism. Heat is Evil. Final Good is Absolute Frigidity. An Arctic winter is very beautiful, but I think that an interest in monkeys chattering in palm trees accounts for our own Intermediatism.

Visitors.

Our confusion here, out of which we are attempting to make quasi-order, is as great as it has been throughout this book, because we have not the positivist's delusion of homogeneity. A positivist would gather all data that seem to relate to one kind of visitors and coldly disregard all other data. I think of as many different kinds of visitors to this earth as there are visitors to New York, to a jail, to a church—some persons go to church to pick pockets, for instance.

My own acceptance is that either a world or a vast super-construction—or a world, if red substances and fishes fell from it—hovered over India in the summer of 1860. Something then fell from somewhere, July 17, 1860, at Dhurmsalla. Whatever "it" was, "it" is so persistently alluded to as "a meteorite" that I look back and see that I adopted this convention myself. But in the London Times, Dec. 26, 1860, Syed Abdoolah, Professor of Hindustani, University College, London, writes that he had sent to a friend in Dhurmsalla, for an account of the stones that had fallen at that place. The answer:

"... divers forms and sizes, many of which bore great resemblance to ordinary cannon balls just discharged from engines of war."

It's an addition to our data of spherical objects that have arrived upon this earth. Note that they are spherical stone objects.

And, in the evening of this same day that something—took a shot at Dhurmsalla—or sent objects upon which there may be decipherable markings—lights were seen in the air—

I think, myself, of a number of things, beings, whatever they were, trying to

Comments (0)