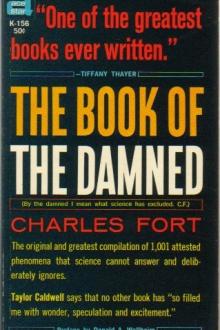

The Book of the Damned - Charles Fort (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned - Charles Fort (best contemporary novels .TXT) 📗». Author Charles Fort

The obvious explanation of this phenomenon is that, under the surface of the sea, in the Persian Gulf, was a vast luminous wheel: that it was the light from its submerged spokes that Mr. Robertson saw, shining upward. It seems clear that this light did shine upward from origin below the surface of the sea. But at first it is not so clear how vast luminous wheels, each the size of a village, ever got under the surface of the Persian Gulf: also there may be some misunderstanding as to what they were doing there.

A deep-sea fish, and its adaptation to a dense medium—

That, at least in some regions aloft, there is a medium dense even to gelatinousness—

A deep-sea fish, brought to the surface of the ocean: in a relatively attenuated medium, it disintegrates—

Super-constructions adapted to a dense medium in inter-planetary space—sometimes, by stresses of various kinds, they are driven into this earth's thin atmosphere—

Later we shall have data to support just this: that things entering this earth's atmosphere disintegrate and shine with a light that is not the light of incandescence: shine brilliantly, even if cold—

Vast wheel-like super-constructions—they enter this earth's atmosphere, and, threatened with disintegration, plunge for relief into an ocean, or into a denser medium.

Of course the requirements now facing us are:

Not only data of vast wheel-like super-constructions that have relieved their distresses in the ocean, but data of enormous wheels that have been seen in the air, or entering the ocean, or rising from the ocean and continuing their voyages.

Very largely we shall concern ourselves with enormous fiery objects that have either plunged into the ocean or risen from the ocean. Our acceptance is that, though disruption may intensify into incandescence, apart from disruption and its probable fieriness, things that enter this earth's atmosphere have a cold light which would not, like light from molten matter, be instantly quenched by water. Also it seems acceptable that a revolving wheel would, from a distance, look like a globe; that a revolving wheel, seen relatively close by, looks like a wheel in few aspects. The mergers of ball-lightning and meteorites are not resistances to us: our data are of enormous bodies.

So we shall interpret—and what does it matter?

Our attitude throughout this book:

That here are extraordinary data—that they never would be exhumed, and never would be massed together, unless—

Here are the data:

Our first datum is of something that was once seen to enter an ocean. It's from the puritanic publication, Science, which has yielded us little material, or which, like most puritans, does not go upon a spree very often. Whatever the thing could have been, my impression is of tremendousness, or of bulk many times that of all meteorites in all museums combined: also of relative slowness, or of long warning of approach. The story, in Science, 5-242, is from an account sent to the Hydrographic Office, at Washington, from the branch office, at San Francisco:

That, at midnight, Feb. 24, 1885, Lat. 37° N., and Long. 170° E., or somewhere between Yokohama and Victoria, the captain of the bark Innerwich was aroused by his mate, who had seen something unusual in the sky. This must have taken appreciable time. The captain went on deck and saw the sky turning fiery red. "All at once, a large mass of fire appeared over the vessel, completely blinding the spectators." The fiery mass fell into the sea. Its size may be judged by the volume of water cast up by it, said to have rushed toward the vessel with a noise that was "deafening." The bark was struck flat aback, and "a roaring, white sea passed ahead." "The master, an old, experienced mariner, declared that the awfulness of the sight was beyond description."

In Nature, 37-187, and L'Astronomie; 1887-76, we are told that an object, described as "a large ball of fire," was seen to rise from the sea, near Cape Race. We are told that it rose to a height of fifty feet, and then advanced close to the ship, then moving away, remaining visible about five minutes. The supposition in Nature is that it was "ball lightning," but Flammarion, Thunder and Lightning, p. 68, says that it was enormous. Details in the American Meteorological Journal, 6-443—Nov. 12, 1887—British steamer Siberian—that the object had moved "against the wind" before retreating—that Captain Moore said that at about the same place he had seen such appearances before.

Report of the British Association, 1861-30:

That, upon June 18, 1845, according to the Malta Times, from the brig Victoria, about 900 miles east of Adalia, Asia Minor (36° 40' 56", N. Lat.: 13° 44' 36" E. Long.), three luminous bodies were seen to issue from the sea, at about half a mile from the vessel. They were visible about ten minutes.

The story was never investigated, but other accounts that seem acceptably to be other observations upon this same sensational spectacle came in, as if of their own accord, and were published by Prof. Baden-Powell. One is a letter from a correspondent at Mt. Lebanon. He describes only two luminous bodies. Apparently they were five times the size of the moon: each had appendages, or they were connected by parts that are described as "sail-like or streamer-like," looking like "large flags blown out by a gentle breeze." The important point here is not only suggestion of structure, but duration. The duration of meteors is a few seconds: duration of fifteen seconds is remarkable, but I think there are records up to half a minute. This object, if it were all one object, was visible at Mt. Lebanon about one hour. An interesting circumstance is that the appendages did not look like trains of meteors, which shine by their own light, but "seemed to shine by light from the main bodies."

About 900 miles west of the position of the Victoria is the town of Adalia, Asia Minor. At about the time of the observation reported by the captain of the Victoria, the Rev. F. Hawlett, F.R.A.S., was in Adalia. He, too, saw this spectacle, and sent an account to Prof. Baden-Powell. In his view it was a body that appeared and then broke up. He places duration at twenty minutes to half an hour.

In the Report of the British Association, 1860-82, the phenomenon was reported from Syria and Malta, as two very large bodies "nearly joined."

Rept. Brit. Assoc., 1860-77:

That, at Cherbourg, France, Jan. 12, 1836, was seen a luminous body, seemingly two-thirds the size of the moon. It seemed to rotate on an axis. Central to it there seemed to be a dark cavity.

For other accounts, all indefinite, but distortable into data of wheel-like objects in the sky, see Nature, 22-617; London Times, Oct. 15, 1859; Nature, 21-225; Monthly Weather Review, 1883-264.

L'Astronomie, 1894-157:

That, upon the morning of Dec. 20, 1893, an appearance in the sky was seen by many persons in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. A luminous body passed overhead, from west to east, until at about 15 degrees in the eastern horizon, it appeared to stand still for fifteen or twenty minutes. According to some descriptions it was the size of a table. To some observers it looked like an enormous wheel. The light was a brilliant white. Acceptably it was not an optical illusion—the noise of its passage through the air was heard. Having been stationary, or having seemed to stand still fifteen or twenty minutes, it disappeared, or exploded. No sound of explosion was heard.

Vast wheel-like constructions. They're especially adapted to roll through a gelatinous medium from planet to planet. Sometimes, because of miscalculations, or because of stresses of various kinds, they enter this earth's atmosphere. They're likely to explode. They have to submerge in the sea. They stay in the sea awhile, revolving with relative leisureliness, until relieved, and then emerge, sometimes close to vessels. Seamen tell of what they see: their reports are interred in scientific morgues. I should say that the general route of these constructions is along latitudes not far from the latitudes of the Persian Gulf.

Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 28-29:

That, upon April 4, 1901, about 8:30, in the Persian Gulf, Captain Hoseason, of the steamship Kilwa, according to a paper read before the Society by Captain Hoseason, was sailing in a sea in which there was no phosphorescence—"there being no phosphorescence in the water."

I suppose I'll have to repeat that:

"... there being no phosphorescence in the water."

Vast shafts of light—though the captain uses the word "ripples"—suddenly appeared. Shaft followed shaft, upon the surface of the sea. But it was only a faint light, and, in about fifteen minutes, died out: having appeared suddenly, having died out gradually. The shafts revolved at a velocity of about 60 miles an hour.

Phosphorescent jellyfish correlate with the Old Dominant: in one of the most heroic compositions of disregards in our experience, it was agreed, in the discussion of Capt. Hoseason's paper, that the phenomenon was probably pulsations of long strings of jellyfish.

Nature, 21-410:

Reprint of a letter from R.E. Harris, Commander of the A.H.N. Co.'s steamship Shahjehan, to the Calcutta Englishman, Jan. 21, 1880:

That upon the 5th of June, 1880, off the coast of Malabar, at 10 P.M., water calm, sky cloudless, he had seen something that was so foreign to anything that he had ever seen before, that he had stopped his ship. He saw what he describes as waves of brilliant light, with spaces between. Upon the water were floating patches of a substance that was not identified. Thinking in terms of the conventional explanation of all phosphorescence at sea, the captain at first suspected this substance. However, he gives his opinion that it did no illuminating but was, with the rest of the sea, illuminated by tremendous shafts of light. Whether it was a thick and oily discharge from the engine of a submerged construction or not, I think that I shall have to accept this substance as a concomitant, because of another note. "As wave succeeded wave, one of the most grand and brilliant, yet solemn, spectacles that one could think of, was here witnessed."

Jour. Roy. Met. Soc., 32-280:

Extract from a letter from Mr. Douglas Carnegie, Blackheath, England. Date some time in 1906—

"This last voyage we witnessed a weird and most extraordinary electric display." In the Gulf of Oman, he saw a bank of apparently quiescent phosphorescence: but, when within twenty yards of it, "shafts of brilliant light came sweeping across the ship's bows at a prodigious speed, which might be put down as anything between 60 and 200 miles an hour." "These light bars were about 20 feet apart and most regular." As to phosphorescence—"I collected a bucketful of water, and examined it under the microscope, but could not detect anything abnormal." That the shafts of light came up from something beneath the surface—"They first struck us on our broadside, and I noticed that an intervening ship had no effect on the light beams: they started away from the lee side of the ship, just as if they had traveled right through it."

The Gulf of Oman is at the entrance to the Persian Gulf.

Jour. Roy. Met. Soc., 33-294:

Extract from a letter by Mr. S.C. Patterson, second officer of the P. and O. steamship Delta: a spectacle which the Journal continues to call phosphorescent:

Malacca Strait, 2 A.M., March 14, 1907:

"... shafts which seemed to move round a center—like the spokes of a wheel—and appeared to be about 300 yards long. The phenomenon lasted about half an hour, during which time the ship had traveled six or seven miles. It stopped suddenly."

L'Astronomie, 1891-312:

A correspondent writes that, in October, 1891, in the China Sea, he had seen shafts or lances of light that had had the appearance of rays of a searchlight, and that had moved like such rays.

Nature, 20-291:

Report to the Admiralty by

Comments (0)