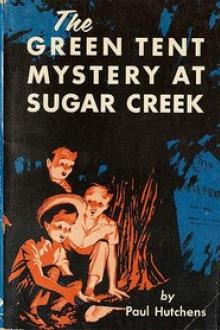

The Green Tent Mystery at Sugar Creek - Paul Hutchens (good english books to read txt) 📗

- Author: Paul Hutchens

- Performer: -

Book online «The Green Tent Mystery at Sugar Creek - Paul Hutchens (good english books to read txt) 📗». Author Paul Hutchens

“Take good care of her,” Mom said, as, all dressed up in her Sunday dress, she looked out the closed car door window.

“I will,” I promised and she and Pop went spinning out through the front gate, past Theodore Collins on the mailbox and onto the highway—their car stirring up a big cloud of white dust, that moved slowly off in the direction of Bumblebee Hill and the old cemetery.

I SHUT the gate after Mom and Pop, and Charlotte Ann and I went hand in hand toward the house to take her nap. That is, her hand was in mine—she not wanting it to be there on account of she knew it was nap time and she didn’t want to take one.

“It’s not hard to take a nap,” I said to her. “You just lie down and shut your eyes and that’s all there is to it. I’m the baby sitter and you are the baby-lying-downer. My first job is to get you to bed, so here we go.”

I was using a very cheerful voice, but she seemed to be suspicious of such a voice coming from me, besides she was still a little tearful from Mom and Pop having gone and left her at home with me.

I realized that I was going to have to use one of Pop’s tricks to get her to want to go to bed—one he used sometimes at night. I had seen him put her to bed maybe a hundred times so I looked down at her and said cheerfully, “O. K., kid. Let’s get going.”

I was surprised at how easy it was at first. It didn’t take long to get her ready ’cause Mom had said she could rest in her play suit, which Mom called her “sunset.” Just like Pop does, I pretended to be a poor, crippled, old grandfather, saying to her with a trembling voice like I was suffering terribly, “I’ve got to get into that other room and I need somebody to help me walk.”

I started limping terribly bad toward the room where she was supposed to sleep, going very slowly like a very crippled old man, staggering and limping and whining and complaining.

If there is anybody she likes better than anybody else, it is Old Man Paddler. She must have imagined that I was him because quick as anything she made a dive in my direction, clasped her small hand around my right knee and held on tight while I limped the best I could with one leg and walked the best I could with the other. We struggled toward the room where her small bed was. All the way there I kept on complaining with a trembling old voice saying, “Poor old man. How can I walk without a nice little girl to help me?”

The very minute we got to her bed—the green window blind being down and it being almost dark—she must have decided to do like she does when it is night when she always says her prayers before getting into bed. Right away she was down on her knees making me get down beside her. I bent my poor, old rheumatic knees down to the hard floor; and without waiting for me to say anything, she started in in her babyish voice trying to say the prayer Pop had been teaching her which is:

It was the same prayer I had used to say myself years and years ago. Sometimes even yet when I kneel down to say a good-night prayer to God and I am very tired and sleepy, before I know it I am saying it myself even though I am too big to say just a little poem prayer.

As quick as her prayer was finished, I swooped her up and flip-flopped her into bed, but for some reason or other she was as wide awake as anything. She didn’t stay lying down, but sat straight up in bed with a mischievous grin all over her cute face. She was the most wide-awake baby I ever saw.

“I want my dolly,” she ordered me in her own language, which is what she always does at night.

“O. K.,” I said, getting it for her from somewhere in the other room where I found it upside-down lying on its face. I handed it to her.

“I want my rag dolly, too,” she said and I said cheerfully, “O. K. I’ll get your dirty-faced rag dolly.” I went to the corner of the room where it was lying on its side with its left foot stuck in its face. I carried it to her and tossed it into the bed with her where it socked her in the cheek, but didn’t hurt. Then I said, “O. K. now. Go to sleep.” I was half way to the door when she called again saying, “I want my ‘puh’”—meaning her little pink dolly-pillow.

I came back and sighed down hard at her and started looking everywhere for her pink pillow, wondering what else she would want and why. I soon found out because next she wanted her “hanky,” which was a pretty colored handkerchief, which Pop had had to get for her every night all summer and which she always held up close to her face when she went to sleep, it being very soft and as Mom said, “Friendly.... She likes to feel secure and all these things help her to feel that way.” Mom also said, “She imagines the dollies are honest-to-goodness people and she feels she isn’t alone when they are with her in bed, and they keep her from being afraid.”

I couldn’t help but think that Poetry, who as you know is always quoting a poem, if he were there, would probably quote one by Robert Louis Stevenson, which goes like this:

For some reason or other as I looked down at her cuddling her dollies, I think I had never liked her so well in my whole life—even though I was still half disgusted with her for making me carry so many things to her. I guess I was a little worried, though, which probably helped me to like her better. I kept thinking about the woman who had been digging holes in the earth who thought Charlotte Ann looked enough like her own dead Elsa to be her twin—in fact, enough like her to be her. I wished the woman would hurry up and get well but she didn’t seem to be improving very much because the gang had kept on finding new holes all around Sugar Creek.

Pretty soon Charlotte Ann’s eyes went shut and stayed shut and her regular breathing showed that she was asleep.

Realizing that at last she was asleep, I went out through the living room into the kitchen and through that. Out-of-doors, I closed the screen door more quietly than it had been closed for a long time and went on out toward the iron pitcher-pump—being suddenly very thirsty.

Halfway to the pump I stopped on the boardwalk and turned around to see if anything was wrong, feeling something was, on account of nearly always by the time I got that far out-of-doors I heard the screen door slam behind me, but this time it hadn’t done it and it was a little bit confusing to me not to hear it.

Baby-sitting was hard work, I thought, and it would be silly to do two long hours of it actually sitting down.

A few tangled-up jiffies later I was up on our grape arbor in a perfect position for eating a piece of pie upside-down but I didn’t have any pie so I couldn’t baby-sit that way.

Pretty soon I was tired of being up on that narrow two-by-four crossbeam, so I wriggled myself down and walked over to the water tank on the other side of the pump where about twenty-seven yellow butterflies, seeing me come, made a scramble in about twenty-seven different fluttering directions of up, then right away the yellow air was quiet again as most of the twenty-seven settled themselves down all around the edge of a little water puddle.

Maybe I could get Pop’s insect book and look up a new insect for him. Maybe I could look up something about yellow butterflies, which laid their eggs on Mom’s cabbage plants and also the green larvae, which hatched out and ate the cabbages. But I wasn’t interested in getting any more education just then.

Spying my personally owned hoe leaning against the tool house on the other side of the grape arbor, an idea popped into my head—and out again quick—to do a few minutes baby-sitting by hoeing a couple of rows of potatoes in the garden just below the pignut trees near which Pop had buried Old Addie’s two red-haired pigs; but for some reason or other I began to feel very tired and I could tell it would be very boring to baby-sit that way.

I mosied along out to where Old Addie was doing her own baby-sitting near a big puddle of water beside her apartment house, lying in some straw that was still clean. She was acting very lazy and sleepy and grunting while her six red-haired, lively youngsters were having a noisy afternoon lunch.

“Pretty soft,” I said down to her but she didn’t act like she even recognized me.

I was remembering a silly little rhyme, which I had heard in school when I was in the first grade and it was:

That gave me an idea so I scrambled out to the orchard, picked up six apples and brought them back, and leaning over the fence called out, “Here, piggy, piggy, piggy. Here are some swell apples. Say ‘please’ and you can have them.”

But they ignored me, not only not saying ‘please’ but probably weren’t even saying ‘thank you’ in pig language to their mother.

So I tossed my six apples over into the hog lot where they rolled up to the open door of Addie’s apartment, and that was the end of her six babies’ afternoon lunch. She shuffled her heavy body to her feet, swung it around and started in on those apples like she was terribly hungry.

“Well, what next?” I thought and wondered if Old Bentcomb, my favorite white hen, who always laid her egg in the nest up in our haymow, had laid her egg yet today. It was too early to gather the eggs, but I could get hers if she had it ready.

Into the barn and up the ladder I went and there she was, with her pretty white neck and head and her long red, bent comb hanging down over her right eye like a lock of brown hair kinda drops down over the right eye of one of Circus’ many sisters, who even though she is kinda ordinary-looking, doesn’t act like she thinks I am a dumbbell like some girls do that go to the Sugar Creek school—and maybe are, themselves.

“Hi, Old Bentcomb,” I said, but she sorta ducked her head down and ignored me.

“Pretty soft life,” I said, “you don’t have to worry about taking care of a baby sister while your parents are away.”

Down the ladder I went and shuffled back across

Comments (0)