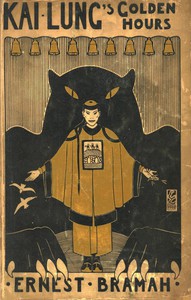

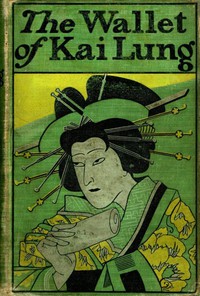

Kai Lung's Golden Hours by Ernest Bramah (books to read for 12 year olds TXT) 📗

- Author: Ernest Bramah

Book online «Kai Lung's Golden Hours by Ernest Bramah (books to read for 12 year olds TXT) 📗». Author Ernest Bramah

“None of these things lies within my admitted powers,” confessed the stranger. “To what end does your gracious inquiry tend?”

“It is in the nature of a warning, for within the shadow of the house you seek manifestations such as I describe pass almost without remark. Indeed it is not unlikely that while in the act of displaying your engaging but simple skill you may find yourself transformed into a chameleon or saddled with the necessity of finishing your gravity-removing entertainment under the outward form of a Manchurian ape.”

“Alas!” exclaimed the other. “The eleventh of the moon was ever this person’s unlucky day, and he would have done well to be warned by a dream in which he saw an unsuspecting kid walk into the mouth of a voracious tiger.”

“Undoubtedly the tiger was an allusion to the dangers awaiting you, but it is not yet too late for you to prove that you are no kid,” counselled Chang Tao. “Take this piece of silver so that the enterprise of the day may not have been unfruitful and depart with all speed on a homeward path. He who speaks is going westward, and at the lattice of Shen Yi he will not fail to leave a sufficient excuse for your no-appearance.”

“Your voice has the compelling ring of authority, beneficence,” replied the stranger gratefully. “The obscure name of the one who prostrates himself is Wo, that of his degraded father being Weh. For this service he binds his ghost to attend your ghost through three cycles of time in the After.”

“It is remitted,” said Chang Tao generously, as he resumed his way. “May the path be flattened before your weary feet.”

Thus, unsought as it were, there was placed within Chang Tao’s grasp a staff that might haply bear his weight into the very presence of Melodious Vision herself. The exact strategy of the undertaking did not clearly yet reveal itself, but “When fully ripe the fruit falls of its own accord,” and Chang Tao was content to leave such detail to the guiding spirits of his destinies. As he approached the outer door he sang cheerful ballads of heroic doings, partly because he was glad, but also to reassure himself.

“One whom he expects awaits,” he announced to the keeper of the gate. “The name of Wo, the son of Weh, should suffice.”

“It does not,” replied the keeper, swinging his roomy sleeve specifically. “So far it has an empty, short-stopping sound. It lacks sparkle; it has no metallic ring.... He sleeps.”

“Doubtless the sound of these may awaken him,” said Chang Tao, shaking out a score of cash.

“Pass in munificence. Already his expectant eyes rebuke the unopen door.”

Although he had been in a measure prepared by Wo, Chang Tao was surprised to find that three persons alone occupied the chamber to which he was conducted. Two of these were Shen Yi and a trusted slave; at the sight of the third Chang Tao’s face grew very red and the deficiencies of his various attributes began to fill his mind with dark forebodings, for this was Melodious Vision and no man could look upon her without her splendour engulfing his imagination. No record of her pearly beauty is preserved beyond a scattered phrase or two; for the poets and minstrels of the age all burned what they had written, in despair at the inadequacy of words. Yet it remains that whatever a man looked for, that he found, and the measure of his requirement was not stinted.

“Greeting,” said Shen Yi, with easy-going courtesy. He was a more meagre man than Chang Tao had expected, his face not subtle, and his manner restrained rather than oppressive. “You have come on a long and winding path; have you taken your rice?”

“Nothing remains lacking,” replied Chang Tao, his eyes again elsewhere. “Command your slave, Excellence.”

“In what particular direction do your agreeable powers of leisure-beguiling extend?”

So far Chang Tao had left the full consideration of this inevitable detail to the inspiration of the moment, but when the moment came the prompting spirits did not disclose themselves. His hesitation became more elaborate under the expression of gathering enlightenment that began to appear in Melodious Vision’s eyes.

“An indifferent store of badly sung ballads,” he was constrained to reply at length, “and—perchance—a threadbare assortment of involved questions and replies.”

“Was it your harmonious voice that we were privileged to hear raised beneath our ill-fitting window a brief space ago?” inquired Shen Yi.

“Admittedly at the sight of this noble palace I was impelled to put my presumptuous gladness into song.”

“Then let it fain be the other thing,” interposed the maiden, with decision. “Your gladness came to a sad end, minstrel.”

“Involved questions are by no means void of divertisement,” remarked Shen Yi, with conciliatory mildness in his voice. “There was one, turning on the contradictory nature of a door which under favourable conditions was indistinguishable from an earthenware vessel, that seldom failed to baffle the unalert in the days before the binding of this person’s hair.”

“That was the one which it had been my feeble intention to propound,” confessed Chang Tao.

“Doubtless there are many others equally enticing,” suggested Shen Yi helpfully.

“Alas,” admitted Chang Tao with conscious humiliation; “of all those wherein I retain an adequate grasp of the solution, the complication eludes me at the moment, and thus in a like but converse manner with the others.”

“Esteemed parent,” remarked Melodious Vision, without emotion, “this is neither a minstrel nor one in any way entertaining. It is merely Another.”

“Another!” exclaimed Chang Tao in refined bitterness. “Is it possible that after taking so extreme and unorthodox a course as to ignore the Usages and advance myself in person I am to find that I have not even the mediocre originality of being the first, as a recommendation?”

“If the matter is thus and thus, so far from being the first, you are only the last of a considerable line of worthy and enterprising youths who have succeeded in gaining access to the inner part of this not really attractive residence on one pretext or another,” replied the tolerant Shen Yi. “In any case you are honourably welcome. From the position of your various features I now judge you to be Tao, only son of the virtuous house of Chang. May you prove more successful in your enterprise than those who have preceded you.”

“The adventure appears to be tending in unforeseen directions,” said Chang Tao uneasily. “Your felicitation, benign, though doubtless gold at heart, is set in a doubtful frame.”

“It is for your stalwart endeavour to assure a happy picture,” replied Shen Yi, with undisturbed cordiality. “You bear a sword.”

“What added involvement is this?” demanded Chang Tao. “This one’s thoughts and intention were not turned towards savagery and arms, but in the direction of a pacific union of two distinguished lines.”

“In such cases my attitude has invariably been one of sympathetic unconcern,” declared Shen Yi. “The weight of either side produces an atmosphere of absolute poise that cannot fail to give full play to the decision of the destinies.”

“But if this attitude is maintained on your part how can the proposal progress to a definite issue?” inquired Chang Tao.

“So far, it never has so progressed,” admitted Shen Yi. “None of the worthy and hard-striving young men—any of whom I should have been overjoyed to greet as a son-in-law had my inopportune sense of impartiality permitted it—has yet returned from the trial to claim the reward.”

“Even the Classics become obscure in the dark. Clear your throat of all doubtfulness, O Shen Yi, and speak to a definite end.”

“That duty devolves upon this person, O would-be propounder of involved questions,” interposed Melodious Vision. Her voice was more musical than a stand of hanging jewels touched by a rod of jade, and each word fell like a separate pearl. “He who ignores the Usages must expect to find the Usages ignored. Since the day when K’ung-tsz framed the Ceremonies much water has passed beneath the Seven Terraced Bridge, and that which has overflowed can never be picked up again. It is no longer enough that you should come and thereby I must go; that you should speak and I be silent; that you should beckon and I meekly obey. Inspired by the uprisen sisterhood of the outer barbarian lands, we of the inner chambers of the Illimitable Kingdom demand the right to express ourselves freely on every occasion and on every subject, whether the matter involved is one that we understand or not.”

“Your clear-cut words will carry far,” said Chang Tao deferentially, and, indeed, Melodious Vision’s voice had imperceptibly assumed a penetrating quality that justified the remark. “Yet is it fitting that beings so superior in every way should be swayed by the example of those who are necessarily uncivilized and rude?”

“Even a mole may instruct a philosopher in the art of digging,” replied the maiden, with graceful tolerance. “Thus among those uncouth tribes it is the custom, when a valiant youth would enlarge his face in the eyes of a maiden, that he should encounter forth and slay dragons, to the imperishable glory of her name. By this beneficent habit not only are the feeble and inept automatically disposed of, but the difficulty of choosing one from among a company of suitors, all apparently possessing the same superficial attributes, is materially lightened.”

“The system may be advantageous in those dark regions,” admitted Chang Tao reluctantly, “but it must prove unsatisfactory in our more favoured land.”

“In what detail?” demanded the maiden, pausing in her attitude of assured superiority.

“By the essential drawback that whereas in those neglected outer parts there really are no dragons, here there really are. Thus—”

“Doubtless there are barbarian maidens for those who prefer to encounter barbarian dragons, then,” exclaimed Melodious Vision, with a very elaborately sustained air of no-concern.

“Doubtless,” assented Chang Tao mildly. “Yet having set forth in the direction of a specific Vision it is this person’s intention to pursue it to an ultimate end.”

“The quiet duck puts his foot on the unobservant worm,” murmured Shen Yi, with delicate encouragement, adding “This one casts a more definite shadow than those before.”

“Yet,” continued the maiden, “to all, my unbending word is this: he who would return for approval must experience difficulties, overcome dangers and conquer dragons. Those who do not adventure on the quest will pass outward from this person’s mind.”

“And those who do will certainly Pass Upward from their own bodies,” ran the essence of the youth’s inner thoughts. Yet the network of her unevadable power and presence was upon him; he acquiescently replied:

“It is accepted. On such an errand difficulties and dangers will not require any especial search. Yet how many dragons slain will suffice to win approval?”

“Crocodile-eyed one!” exclaimed Melodious Vision, surprised into wrathfulness. “How many—” Here she withdrew in abrupt vehemence.

“Your progress has been rapid and profound,” remarked Shen Yi, as, with flattering attention, he accompanied Chang Tao some part of the way towards the door. “Never before has that one been known to leave a remark unsaid; I do not altogether despair of seeing her married yet. As regards the encounter with the dragon—well, in the case of the one whispering in your ear there was the revered mother of the one whom he sought. After all, a dragon is soon done with—one way or the other.”

In such a manner Chang Tao set forth to encounter dragons, assured that difficulties and dangers would accompany him on either side. In this latter detail he was inspired, but as the great light faded and the sky-lantern rose in interminable succession, while the unconquerable li ever stretched before his expectant feet, the essential part of the undertaking began to assume a dubious facet. In the valleys and fertile places he learned that creatures of this part now chiefly inhabited the higher fastnesses, such regions being more congenial to their wild and intractable natures. When, however, after many laborious marches he reached the upper peaks of pathless mountains the scanty crag-dwellers did not vary in their assertion that the dragons had for some time past forsaken those heights for the more settled profusion of the plains. Formerly, in both places they had been plentiful, and all those whom Chang Tao questioned spoke openly of many encounters between their immediate forefathers and such Beings.

It was in the downcast frame of mind to which the delays in accomplishing his mission gave rise that Chang Tao found himself walking side by side with one who bore the

Comments (0)