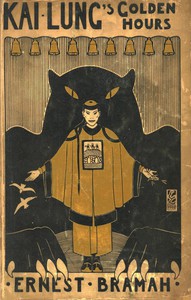

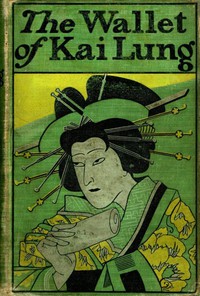

Kai Lung's Golden Hours by Ernest Bramah (books to read for 12 year olds TXT) 📗

- Author: Ernest Bramah

Book online «Kai Lung's Golden Hours by Ernest Bramah (books to read for 12 year olds TXT) 📗». Author Ernest Bramah

“The shadow moves as the sun directs,” replied Kai Lung, and with courteous afterthought he added the wonted parting: “Slowly, slowly; walk slowly.”

In such a manner the story-teller found himself in a highly-walled enclosure, lying between the prison-house and the yamen garden, a few days after his arrival in Yu-ping. Ming-shu had not eaten his word.

The yard itself possessed no attraction for Kai Lung. Almost before Li-loe had disappeared he was at the shutter in the wall, had forced it open and was looking out. Thus long he waited, motionless, but observing every leaf that stirred among the trees and shrubs and neglected growth beyond. At last a figure passed across a distant glade and at the sight Kai Lung lifted up a restrained voice in song:

“At the foot of a bleak and inhospitable mountain

An insignificant stream winds its uncared way;

Although inferior to the Yangtze-kiang in every detail

Yet fish glide to and fro among its crannies

Nor would they change their home for the depths of the widest river.

The palace of the sublime Emperor is made rich with hanging curtains.

While here rough stone walls forbid repose.

Yet there is one who unhesitatingly prefers the latter;

For from an open shutter here he can look forth,

And perchance catch a glimpse of one who may pass by.

The occupation of the Imperial viceroy is both lucrative and noble;

While that of a relater of imagined tales is by no means esteemed.

But he who thus expressed himself would not exchange with the other;

For around the identity of each heroine he can entwine the personality of one whom he has encountered.

And thus she is ever by his side.”

“Your uplifted voice comes from an unexpected quarter, minstrel,” said a melodious voice, and the maiden whom he had encountered in the wood stood before him. “What crime have you now committed?”

“An ancient one. I presumed to raise my unworthy eyes—”

“Alas, story-teller,” interposed the maiden hastily, “it would seem that the star to which you chained your wrist has not carried you into the assembly of the gods.”

“Yet already it has borne me half-way—into a company of malefactors. Doubtless on the morrow the obliging Mandarin Shan Tien will arrange for the journey to be complete.”

“Yet have you then no further wish to continue in an ordinary existence?” asked the maiden.

“To this person,” replied Kai Lung, with a deep-seated look, “existence can never again be ordinary. Admittedly it may be short.”

As they conversed together in this inoffensive manner she whom Li-loe had called the Golden Mouse held in her delicately-formed hands a priceless bowl filled with ripe fruit of the rarer kinds which she had gathered. These from time to time she threw up to the opening, rightly deciding that one in Kai Lung’s position would stand in need of sustenance, and he no less dexterously held and retained them. When the bowl was empty she continued for a space to regard it silently, as though exploring the many-sided recesses of her mind.

“You have claimed to be a story-teller and have indeed made a boast that there is no arising emergency for which you are unprepared,” she said at length. “It now befalls that you may be put to a speedy test. Is the nature of this imagined scene”—thus she indicated the embellishment of the bowl—“familiar to your eyes?”

“It is that known as ‘The Willow,’” replied Kai Lung. “There is a story—”

“There is a story!” exclaimed the maiden, loosening from her brow the overhanging look of care. “Thus and thus. Frequently have I importuned him before whom you will appear to explain to me the meaning of the scene. When you are called upon to plead your cause, see to it well that your knowledge of such a tale is clearly shown. He before whom you kneel, craftily plied meanwhile by my unceasing petulance, will then desire to hear it from your lips... At the striking of the fourth gong the day is done. What lies between rests with your discriminating wit.”

“You are deep in the subtler kinds of wisdom, such as the weak possess,” confessed Kai Lung. “Yet how will this avail to any length?”

“That which is put off from to-day is put off from to-morrow,” was the confident reply. “For the rest—at a corresponding gong-stroke of each day it is this person’s custom to gather fruit. Farewell, minstrel.”

When Li-loe returned a little later Kai Lung threw his two remaining strings of cash about that rapacious person’s neck and embraced him as he exclaimed:

“Chieftain among doorkeepers, when I go to the Capital to receive the all-coveted title ‘Leaf-crowned’ and to chant ceremonial odes before the Court, thou shalt accompany me as forerunner, and an agile tribe of selected goats shall sport about thy path.”

“Alas, manlet,” replied the other, weeping readily, “greatly do I fear that the next journey thou wilt take will be in an upward or a downward rather than a sideway direction. This much have I learned, and to this end, at some cost admittedly, I enticed into loquacity one who knows another whose brother holds the key of Ming-shu’s confidence: that to-morrow the Mandarin will begin to distribute justice here, and out of the depths of Ming-shu’s malignity the name of Kai Lung is the first set down.”

“With the title,” continued Kai Lung cheerfully, “there goes a sufficiency of taels; also a vat of a potent wine of a certain kind.”

“If,” suggested Li-loe, looking anxiously around, “you have really discovered hidden about this place a secret store of wine, consider well whether it would not be prudent to entrust it to a faithful friend before it is too late.”

It was indeed as Li-loe had foretold. On the following day, at the second gong-stroke after noon, the order came and, closely guarded, Kai Lung was led forth. The middle court had been duly arranged, with a formidable display of chains, weights, presses, saws, branding irons and other implements for securing justice. At the head of a table draped with red sat the Mandarin Shan Tien, on his right the secretary of his hand, the contemptible Ming-shu. Round about were positioned others who in one necessity or another might be relied upon to play an ordered part. After a lavish explosion of fire-crackers had been discharged, sonorous bells rung and gongs beaten, a venerable geomancer disclosed by means of certain tests that all doubtful influences had been driven off and that truth and impartiality alone remained.

“Except on the part of the prisoners, doubtless,” remarked the Mandarin, thereby imperilling the gravity of all who stood around.

“The first of those to prostrate themselves before your enlightened clemency, Excellence, is a notorious assassin who, under another name, has committed many crimes,” began the execrable Ming-shu. “He confesses that, now calling himself Kai Lung, he has recently journeyed from Loo-chow, where treason ever wears a smiling face.”

“Perchance he is saddened by our city’s loyalty,” interposed the benign Shan Tien, “for if he is smiling now it is on the side of his face removed from this one’s gaze.”

“The other side of his face is assuredly where he will be made to smile ere long,” acquiesced Ming-shu, not altogether to his chief’s approval, as the analogy was already his. “Furthermore, he has been detected lurking in secret meeting-places by the wayside, and on reaching Yu-ping he raised his rebellious voice inviting all to gather round and join his unlawful band. The usual remedy in such cases during periods of stress, Excellence, is strangulation.”

“The times are indeed pressing,” remarked the agile-minded Mandarin, “and the penalty would appear to be adequate.” As no one suffered inconvenience at his attitude, however, Shan Tien’s expression assumed a more unbending cast.

“Let the witnesses appear,” he commanded sharply.

“In so clear a case it has not been thought necessary to incur the expense of hiring the usual witnesses,” urged Ming-shu; “but they are doubtless clustered about the opium floor and will, if necessary, testify to whatever is required.”

“The argument is a timely one,” admitted the Mandarin. “As the result cannot fail to be the same in either case, perhaps the accommodating prisoner will assist the ends of justice by making a full confession of his crimes?”

“High Excellence,” replied the story-teller, speaking for the first time, “it is truly said that that which would appear as a mountain in the evening may stand revealed as a mud-hut by the light of day. Hear my unpainted word. I am of the abject House of Kai and my inoffensive rice is earned as a narrator of imagined tales. Unrolling my threadbare mat at the middle hour of yesterday, I had raised my distressing voice and announced an intention to relate the Story of Wong Ts’in, that which is known as ‘The Legend of the Willow Plate Embellishment,’ when a company of armed warriors, converging upon me—”

“Restrain the melodious flow of your admitted eloquence,” interrupted the Mandarin, veiling his arising interest. “Is the story, to which you have made reference, that of the scene widely depicted on plates and earthenware?”

“Undoubtedly. It is the true and authentic legend as related by the eminent Tso-yi.”

“In that case,” declared Shan Tien dispassionately, “it will be necessary for you to relate it now, in order to uphold your claim. Proceed.”

“Alas, Excellence,” protested Ming-shu from a bitter throat, “this matter will attenuate down to the stroke of evening rice. Kowtowing beneath your authoritative hand, that which the prisoner only had the intention to relate does not come within the confines of his evidence.”

“The objection is superficial and cannot be sustained,” replied Shan Tien. “If an evilly-disposed one raised a sword to strike this person, but was withheld before the blow could fall, none but a leper would contend that because he did not progress beyond the intention thereby he should go free. Justice must be impartially upheld and greatly do I fear that we must all submit.”

With these opportune words the discriminating personage signified to Kai Lung that he should begin.

The Story of Wong Ts’in and the Willow Plate EmbellishmentWong Ts’in, the rich porcelain maker, was ill at ease within himself. He had partaken of his customary midday meal, flavoured the repast by unsealing a jar of matured wine, consumed a little fruit, a few sweetmeats and half a dozen cups of unapproachable tea, and then retired to an inner chamber to contemplate philosophically from the reposeful attitude of a reclining couch.

But upon this occasion the merchant did not contemplate restfully. He paced the floor in deep dejection and when he did use the couch at all it was to roll upon it in a sudden access of internal pain. The cause of his distress was well known to the unhappy person thus concerned, nor did it lessen the pangs of his emotion that it arose entirely from his own ill-considered action.

When Wong Ts’in had discovered, by the side of a remote and obscure river, the inexhaustible bed of porcelain clay that ensured his prosperity, his first care was to erect adequate sheds and labouring-places; his next to build a house sufficient for himself and those in attendance round about him.

So far prudence had ruled his actions, for there is a keen edge to the saying: “He who sleeps over his workshop brings four eyes into the business,” but in one detail Wong Ts’in’s head and feet went on different journeys, for with incredible oversight he omitted to secure the experience of competent astrologers and omen-casters in fixing the exact site of his mansion.

The result was what might have been expected. In excavating for the foundations, Wong Ts’in’s slaves disturbed the repose of a small but rapacious earth-demon that had already been sleeping there for nine hundred and ninety-nine years. With the insatiable cunning of its kind, this vindictive creature waited until the house was completed and then proceeded to transfer its unseen but formidable presence to the quarters that were designed for Wong Ts’in himself. Thenceforth, from time to time, it continued to revenge itself for the trouble to which it had been put by an insidious persecution. This frequently took the form of fastening its claws upon the merchant’s digestive organs, especially after he had partaken of an unusually rich repast (for in some way the display of certain viands excited its unreasoning animosity), pressing heavily upon his chest, invading his repose with dragon-dreams while he slept, and the like. Only by the exercise of an ingenuity greater than its own could Wong Ts’in succeed in baffling its ill-conditioned spite.

On this occasion, recognizing from the nature of his pangs what was taking place, Wong Ts’in resorted to a stratagem that rarely failed him. Announcing in a loud voice that it was his intention to refresh the surface of his body by

Comments (0)