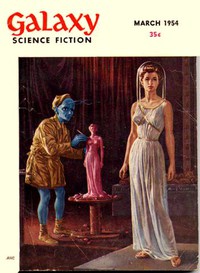

The Telenizer by Don Thompson (classic literature books .txt) 📗

- Author: Don Thompson

Book online «The Telenizer by Don Thompson (classic literature books .txt) 📗». Author Don Thompson

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction March 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

When I saw the blood dripping from the tap in the bathtub, I knew that someone had a telenosis beam on me, and I breathed a very audible sigh of relief.

During the past few days, I had begun to wonder if I was really cracking up.

When you start seeing visions of a bearded gent with a halo, or having vague but wonderful dreams about some sort of perfect world, feeling intense loyalties to undefined ideals, and experiencing sudden impulses, sometimes cruel and sometimes kind—you know that something's wrong.

At least I do.

If he—whoever he was—had just kept up the slow, subtle pace he'd maintained for the past two or three days, he would have had me in a little while. For whatever he wanted.

But now, he'd overplayed his hand. I knew, at least, what was going on. Who was doing it, or why, I still didn't know—nor whether I could stand it, even knowing.

The thick, bright red blood dripping steadily from the water tap in the bath tub wasn't so bad.

I stood before the mirror, with my softly humming razor in my hand, and I watched the blood ooze from the tap, quiver as it grew heavy and pregnant, then pull itself free and fall with a dull plonk to the enamel as another drop began to form.

That wasn't so bad. But my sigh of relief became a gurgle of almost hysterical apprehension as I braced myself for what might come, with the telenizer knowing that I was aware.

There was something I could do—should do—but my mind refused to focus. It bogged down in a muck of unreasoning terror and could only scream Why? Why? Why?

The drops of blood from the water tap increased both in size and rapidity, as I watched. Heavy, red, marble-sized tears followed one another from the tap, plonk, plonk, plonk, splashing in the tub and on the floor. Faster and faster, and then the drip became a flow, a gush, as though the vein of some giant creature had been slashed.

The tub filled rapidly, and blood flowed like a crimson waterfall over the edge and across the floor toward me.

I heard a tiny howling, and looked down.

I screamed and threw the soft, brown, fuzzy, squirming puppy-thing that had been a razor into the advancing tide of blood.

The fuzzy thing shattered when it hit the blood, and each of the thousand pieces became another tiny puppy-thing that grew and grew, yapping and swimming in the blood. The tide was now rising about my shoes.

I backed away from the mirror, trembling violently. I forced myself to slosh through the thick blood into the bedroom, groping for a bottle of whisky on the bureau.

"What the hell are you doing here?" the boss asked when I opened his office door and peeked in. "You're supposed to be in Palm Beach. Well, damn it, come on in!"

I clung to the door firmly as I maneuvered myself through the opening. And when I closed the door, I leaned back against it heavily.

I could see the boss—Carson Newell, managing editor of Intergalaxy News Service—half rising from behind his big desk across the room; but he was pretty dim and I couldn't get him to stay in one place. His voice was clear enough, though:

"Must be mighty important to bring you back from.... Damn it, Langston, are you drunk?"

I grinned then, and said, "Carshon. Carton. Old boy. Do you know that telenosis therapy is no sonofabitchin' good on alcoholics?"

Carson Newell sat back down, frowning.

I stumbled to a chair by the corner of his desk and gripped the arms tightly.

"Telenosis therapy," I repeated, "is just no—"

"Snap out of it," Newell barked. "It's no good on dumb animals, either, and you're probably out of range by now, anyway."

He took a small bottle from his desk and tossed a yellow Anti-Alch pill across the desk to me. I popped it into my mouth.

It didn't take long to work. A few minutes later, still weak and a little trembly, I said, "Would have thought of that myself, if I hadn't been so damn drunk."

The boss grunted. "Now what's this business about telenosis?"

"Somebody's been using it on me," I said. "Maliciously. Damn near drowned in a lake of blood from a water faucet."

"Couldn't have been DTs?"

"I'm serious. It's been going on for three or four days now. Not the blood. That's what gave it away. But other things."

"You've been working pretty hard lately," Newell reminded me.

"Which is why I'm on vacation and all nice and relaxed. Or at least, I was. No, it's not that. Listen, Carson, I admit that I'm no technical expert on telenosis. But a long time ago—seven or eight years ago, I guess—I did a feature series on it. I learned a little bit. Enough to save my life this time."

Newell shrugged. "Okay. You probably know more about it than I do. I just know it's damned restricted stuff." He paused thoughtfully. "Any missing telenizer equipment would cause a helluva fuss, and there hasn't been any fuss."

"No machines in Palm Beach or vicinity that somebody on the inside could be using illegally?" And then I answered that question myself: "No ... I doubt it. The machines are used only in the larger hospitals."

"Don't suppose you have any hunches?"

I shook my head slowly, frowning. "You couldn't really call it a hunch. Just a bare possibility. But I noticed on a news report the other day that Isaac Grogan—you know, 'the Millionaire Mayor of Memphis,' released about a month ago, bribery and corruption sentence—anyway, he's taken up temporary residence in Palm Beach."

The boss rubbed his chin. "As I recall, you did an expos� series on him four or five years ago. Corroborated by official investigation, and Grogan was later sentenced. You thinks he's after revenge?"

I raised a hand warningly. "Now, hold on—I said it was a bare possibility. All I know is that Grogan hates my guts—or might think he has some reason to. I know that Grogan is in Palm Beach, and that I've been under telenosis attack. There's no necessary connection at all."

"No," Newell said. "But it's something to start on." He looked at his wrist watch. "Tell you what. It's nearly noon now. Let's go out for lunch, and while I'm thinking, you can tell me all you remember about telenosis."

It's altogether possible that you may have no more than barely heard of telenosis—its technical details are among the most closely guarded secrets of our time. So I'll go over some of the high spots of what I told Newell.

Mind you, I'm no authority on the subject, and it has been a full seven years since I have done any research on it. However, I learned all I know from Dr. Homer Reighardt, who, at the time, was the world's outstanding authority.

Telenosis, nowadays, is confined almost exclusively to use in psychiatric hospitals and corrective institutions. It's used chiefly on neurotics. In cases of extreme dementia, it's worthless. In fact, the more normal you are, the more effective the telenosis.

Roughly—without going into any of the real technicalities—it's this way:

Science has known for a long time that electrical waves emanate from the brain. The waves can be measured on an electroencaphalograph, and vary with the physiological and psychological condition of the individual. Extreme paranoia, for example, or epilepsy, or alcoholism are accompanied by violent disturbances of the waves.

Very interesting, but....

It wasn't until 2037 that Professor Martin James decided that these brain waves are comparable to radio waves, and got busy inventing a device to listen in on them.

The result, of course, was telenosis. The machine that James came up with, after twenty years of work, could not only listen in on a person's thoughts, which are carried on the brain waves, but it could transmit messages to the brain from the outside.

"Unless the waves are in a state of disturbance caused by alcohol or insanity or some such thing?" Newell commented.

I nodded.

"The word 'telenosis' comes from 'hypnosis,' doesn't it?"

"Yes, but not very accurately," I said. "In hypnosis, you need some sort of visual or auditory accompaniment. With telenosis, you can gain control of a person's mind directly, through the brain waves."

"You say 'gain control of a person's mind,'" Newell said. "Do you mean that if you tell someone who is under telenosis to do something, he's got to do it?"

"Not necessarily," I said. "All you can do with telenosis is transmit thoughts to a person—counting visual and auditory sensations as thoughts. If you can convince him that the thoughts you're sending are his thoughts ... then you can make him do almost anything. But if he knows or suspects he's being telenized—"

"I'm with you," Newell interrupted. "He still gets the thoughts—visions and sounds or what have you—but he doesn't have to obey them."

I nodded. My mind was skipping ahead to more immediate problems. "Don't you suppose we ought to notify Central Investigation Division right away? This is really a problem for them."

But Newell was there ahead of me. "So was the Memphis affair," he said.

I raised my eyebrows.

"Meaning," the boss continued, "that I'd like to give your hunch a play first."

"But it's not even a hunch," I objected. "How?"

"Well, by having you interview Grogan, for instance...."

I opened my mouth and almost shook my head, but Newell hurried on. "Look, Earl, it's been a long time since Intergalaxy has scored a good news beat. Not since the Memphis expos�, in fact. Remember that? Remember how good it felt to have your name on articles published all over the world? Remember all the extra cash? The fame?"

I grunted.

"Now before you say anything," Newell said, "remember that when you started on that case you didn't have a thing more concrete to go on than you have right now—just a half a hunch. Isn't that right? Admit it!"

"M'm."

"Well, isn't it worth a chance? What can we lose?"

"Me, maybe. But...."

The boss said nothing more. He knew that if he let me do the talking, I'd soon argue myself into it. Which I did.

Five minutes later, I shrugged. "Okay. What, specifically, do you have in mind?"

"Let's go back to the office," Newell said.

It was just a short walk. Or, I should say, it would have been a short walk, if we had walked.

But New York was one of the very last cities to convert to the "level" transportation system. It had been one hell of an engineering feat, but for Amerpean ingenuity and enterprise nothing is impossible, so the job had finally been tackled and completed just within the past year. And the novelty of the ambulator bands on pedestrian levels was still strong for native New Yorkers.

So instead of leaving the restaurant on the vehicle level, where we happened to be, and taking an old fashioned sidewalk stroll to the IGN building, Newell insisted on taking the escalator up to the next level and then gliding along on an amband.

That's just the sort of person he is.

When we got back up to his office, he asked, "Isn't there some sort of defense against telenosis? I mean, other than alcohol or insanity?"

I thought for a moment. "Shouldn't be too hard to devise one. All you need is something to set up interference vibrations on the same band as the brain waves you're guarding."

"Sounds simple as hell. Could one of our men do it?"

"A telenosis technician at one of the hospitals could do it quicker," I suggested.

"Without the sanction of C.I.D.? I doubt that."

"That's right," I agreed. "Okay. I'll run down to Technology and see what we can work out. It may take two or three days—"

"I'll see that it gets top priority. I want you to get back to Palm Beach as soon as you can."

As I was getting up to leave, Newell said, "Say, by the way, how's that health cult in Palm Beach—Suns-Rays Incorporated? Anything on that?"

Suns-Rays Incorporated was one of the chief reasons I was taking my vacation in Palm Beach, Fla., instead of in Sacramento, Calif., my home town. Carson Newell had heard about this crackpot religious group that was having a convention in Palm Beach, and he couldn't see why one of his reporters shouldn't combine

Comments (0)