The Book by Michael Shaara (easy to read books for adults list TXT) 📗

- Author: Michael Shaara

Book online «The Book by Michael Shaara (easy to read books for adults list TXT) 📗». Author Michael Shaara

Transcriber's Note:

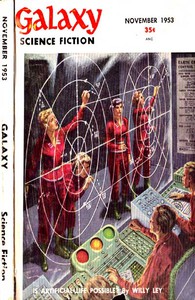

This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction November 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

A weird world—cut off from the Universe, it had universal wisdom; facing death at every moment, it had the secret of peace!

By MICHAEL SHAARA

Illustrated by Mel Hunter

eauclaire was given his first ship at Sirius. He was called up before the Commandant in the slow heat of the afternoon, and stood shuffling with awkward delight upon the shaggy carpet. He was twenty-five years old, and two months out of the Academy. It was a wonderful day.

The Commandant told Beauclaire to sit down, and sat looking at him for a long while. The Commandant was an old man with a face of many lines. He was old, was hot, was tired. He was also very irritated. He had reached that point of oldness when talking to a young man is an irritation because they are so bright and certain and don't know anything and there is nothing you can do about it.

"All right," the Commandant said, "there are a few things I have to tell you. Do you know where you are going?"

"No, sir," Beauclaire said cheerfully.

"All right," the Commandant said again, "I'll tell you. You are going to the Hole in Cygnus. You've heard of it, I hope? Good. Then you know that the Hole is a large dust cloud—estimated diameter, ten light-years. We have never gone into the Hole, for a number of reasons. It's too thick for light speeds, it's too big, and Mapping Command ships are being spread thin. Also, until now, we never thought there was anything in the Hole worth looking at. So we have never gone into the Hole. Your ship will be the first."

"Yes, sir," Beauclaire said, eyes shining.

"A few weeks ago," the Commandant said, "one of our amateurs had a lens on the Hole, just looking. He saw a glow. He reported to us; we checked and saw the same thing. There is a faint light coming out of the Hole—obviously, a sun, a star inside the cloud, just far enough in to be almost invisible. God knows how long it's been there, but we do know that there's never been a record of a light in the Hole. Apparently this star orbited in some time ago, and is now on its way out. It is just approaching the edge of the cloud. Do you follow me?"

"Yes, sir," Beauclaire said.

"Your job is this: You will investigate that sun for livable planets and alien life. If you find anything—which is highly unlikely—you are to decipher the language and come right back. A Psych team will go out and determine the effects of a starless sky upon the alien culture—obviously, these people will never have seen the stars."

he Commandant leaned forward, intent now for the first time.

"Now, this is an important job. There were no other linguists available, so we passed over a lot of good men to pick you. Make no mistake about your qualifications. You are nothing spectacular. But the ship will be yours from now on, permanently. Have you got that?"

The young man nodded, grinning from ear to ear.

"There is something else," the Commandant said, and abruptly he paused.

He gazed silently at Beauclaire—at the crisp gray uniform, the baby-slick cheek—and he thought fleetingly and bitterly of the Hole in Cygnus which he, an old man, would never see. Then he told himself sternly to leave off self-pity. The important thing was coming up, and he would have to say it well.

"Listen," he said. The tone of his voice was very strong and Beauclaire blinked. "You are replacing one of our oldest men. One of our best men. His name is Billy Wyatt. He—he has been with us a long time." The Commandant paused again, his fingers toying with the blotter on his desk. "They have told you a lot of stuff at the Academy, which is all very important. But I want you to understand something else: This Mapping Command is a weary business—few men last for any length of time, and those that do aren't much good in the end. You know that. Well, I want you to be very careful when you talk to Billy Wyatt; and I want you to listen to him, because he's been around longer than anybody. We're relieving him, yes, because he is breaking down. He's no good for us any more; he has no more nerve. He's lost the feeling a man has to have to do his job right."

The Commandant got up slowly and walked around in front of Beauclaire, looking into his eyes.

"When you relieve Wyatt, treat him with respect. He's been farther and seen more than any man you will ever meet. I want no cracks and no pity for that man. Because, listen, boy, sooner or later the same thing will happen to you. Why? Because it's too big—" the Commandant gestured helplessly with spread hands—"it's all just too damn big. Space is never so big that it can't get bigger. If you fly long enough, it will finally get too big to make any sense, and you'll start thinking. You'll start thinking that it doesn't make sense. On that day, we'll bring you back and put you into an office somewhere. If we leave you alone, you lose ships and get good men killed—there's nothing we can do when space gets too big. That is what happened to Wyatt. That is what will happen, eventually, to you. Do you understand?"

The young man nodded uncertainly.

"And that," the Commandant said sadly, "is the lesson for today. Take your ship. Wyatt will go with you on this one trip, to break you in. Pay attention to what he has to say—it will mean something. There's one other crewman, a man named Cooper. You'll be flying with him now. Keep your ears open and your mouth shut, except for questions. And don't take any chances. That's all."

Beauclaire saluted and rose to go.

"When you see Wyatt," the Commandant said, "tell him I won't be able to make it down before you leave. Too busy. Got papers to sign. Got more damn papers than the chief has ulcers."

The young man waited.

"That, God help you, is all," said the Commandant.

yatt saw the letter when the young man was still a long way off. The white caught his eye, and he watched idly for a moment. And then he saw the fresh green gear on the man's back and the look on his face as he came up the ladder, and Wyatt stopped breathing.

He stood for a moment blinking in the sun. Me? he thought ... me?

Beauclaire reached the platform and threw down his gear, thinking that this was one hell of a way to begin a career.

Wyatt nodded to him, but didn't say anything. He accepted the letter, opened it and read it. He was a short man, thick and dark and very powerful. The lines of his face did not change as he read the letter.

"Well," he said when he was done, "thank you."

There was a long wait, and Wyatt said at last: "Is the Commandant coming down?"

"No, sir. He said he was tied up. He said to give you his best."

"That's nice," Wyatt said.

After that, neither of them spoke. Wyatt showed the new man to his room and wished him good luck. Then he went back to his cabin and sat down to think.

After 28 years in the Mapping Command, he had become necessarily immune to surprise; he could understand this at once, but it would be some time before he would react. Well, well, he said to himself; but he did not feel it.

Vaguely, flicking cigarettes onto the floor, he wondered why. The letter had not given a reason. He had probably flunked a physical. Or a mental. One or the other, each good enough reason. He was 47 years old, and this was a rough business. Still, he felt strong and cautious, and he knew he was not afraid. He felt good for a long while yet ... but obviously he was not.

Well, then, he thought, where now?

He considered that with interest. There was no particular place for him to go. Really no place. He had come into the business easily and naturally, knowing what he wanted—which was simply to move and listen and see. When he was young, it had been adventure alone that drew him; now it was something else he could not define, but a thing he knew he needed badly. He had to see, to watch ... and understand.

It was ending, the long time was ending. It didn't matter what was wrong with him. The point was that he was through. The point was that he was going home, to nowhere in particular.

When evening came, he was still in his room. Eventually he'd been able to accept it all and examine it clearly, and had decided that there was nothing to do. If there was anything out in space which he had not yet found, he would not be likely to need it.

He left off sitting, and went up to the control room.

ooper was waiting for him. Cooper was a tall, bearded, scrawny man with a great temper and a great heart and a small capacity for liquor. He was sitting all alone in the room when Wyatt entered.

Except for the pearl-green glow of dashlights from the panel, the room was dark. Cooper was lying far back in the pilot's seat, his feet propped up on the panel. One shoe was off, and he was carefully pressing buttons with his huge bare toes. The first thing Wyatt saw when he entered was the foot glowing luridly in the green light of the panel. Deep within the ship he could hear the hum of the dynamos starting and stopping.

Wyatt grinned. From the play of Coop's toes, and the attitude, and the limp, forgotten pole of an arm which hung down loosely from the chair, it was obvious that Coop was drunk. In port, he was usually drunk. He was a lean, likable man with very few cares and no manners at all, which was typical of men in that Command.

"What say, Billy?" Coop mumbled from deep in the seat.

Wyatt sat down. "Where you been?"

"In the port. Been drinkin' in the goddam port. Hot!"

"Bring back any?"

Coop waved an arm floppily in no particular direction. "Look around."

The flasks lay in a heap by the door. Wyatt took one and sat down again. The room was warm and green and silent. The two men had been together long enough to be able to sit without speaking, and in the green glow they waited, thinking. The first pull Wyatt took was long and numbing; he closed his eyes.

Coop did not move at all. Not even his toes. When Wyatt had begun to think he was asleep, he said suddenly:

"Heard about the replacement."

Wyatt looked at him.

"Found out this afternoon," Coop said, "from the goddam Commandant."

Wyatt closed his eyes again.

"Where you goin'?" Coop asked.

Wyatt shrugged. "Plush job."

"You got any plans?"

Wyatt shook his head.

Coop swore moodily. "Never let you alone," he muttered. "Miserable bastards." He rose up suddenly in the chair, pointing a long matchstick finger into Wyatt's face. "Listen, Billy," he said with determination, "you was a good man, you know that? You was one hell of a good goddam man."

Wyatt took another long pull and nodded, smiling.

"You said it," he said.

"I sailed with some good men, some good men," Coop insisted, stabbing shakily but emphatically with his finger, "but you don't take nothin' from nobody."

"Here's to me, I'm true blue," Wyatt grinned.

oop sank back in the chair, satisfied. "I just wanted you should know. You been a good man."

"Betcher sweet life," Wyatt said.

"So they throw you out. Me they keep. You they throw out. They got no brains."

Wyatt lay back, letting the liquor take hold, receding without pain into a quiet world. The ship was good to feel around him, dark and throbbing like a living womb. Just like a womb, he thought. It's a lot like a womb.

"Listen," Coop said thickly, rising from

Comments (0)