Never Come Midnight by H. L. Gold (read dune .txt) 📗

- Author: H. L. Gold

Book online «Never Come Midnight by H. L. Gold (read dune .txt) 📗». Author H. L. Gold

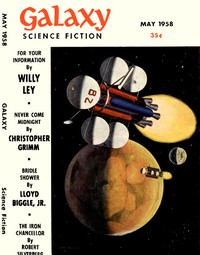

by CHRISTOPHER GRIMM

Illustrated by DILLON

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction May 1958.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Across the void came a man who could not ever

have been born—from a world that could never

have been conceived—to demand his birthright

of an Earth that would have to die to pay it!

I

Jan Shortmire smiled. "You didn't know I had a son, did you, Peter? Well, neither did I—until quite recently."

"I see." However, Peter Hubbard knew that Jan Shortmire had never married in all of his hundred and fifty-five years. In that day and age, unmarried people did not have children; science, the law, and public sophistication had combined to make the historical "accident" almost impossible. Yet, if some woman of one of the more innocent planets had deliberately conceived in order to trap Shortmire, surely he would have learned of his son's existence long before.

"I'm glad it turns out that I have an heir," Shortmire went on. "Otherwise, the government might get its fists on what little I have—and it's taken enough from me."

Although the old man's estate was a considerable one, it did seem meager in terms of the money he must have made. What had become of the golden tide that had poured in upon the golden youth, Hubbard wondered. Could anyone have squandered such prodigious sums upon the usual mundane dissipations? For, by the time the esoteric pleasures of the other planets had reached Earth—the byproduct of Shortmire's own achievement—he must have already been too old to enjoy them.

At Hubbard's continued silence, Shortmire said defensively, "If they'd let me sell my patents to private industry, as Dyall was able to do, I'd be leaving a real fortune!" His voice grew thick with anger. "When I think how much money Dyall made from those factory machines of his...."

But when you added the priceless extra fifty years of life to the money Shortmire had made, it seemed to Hubbard that Shortmire had been amply rewarded. Although, of course, he had heard that Nicholas Dyall had been given the same reward. No point telling Shortmire, if he did not know already. Hubbard could never understand why Shortmire hated Dyall so; it could not be merely the money—and as for reputation, he had a shade the advantage.

"That toymaker!" Shortmire spat.

Hubbard tactfully changed the subject. "What's your boy like, Jan?" But of course Jan Shortmire's son could hardly be a boy; in fact, he was probably almost as old as Hubbard was.

Such old age as Shortmire's was almost incredible. Sitting there in the antique splendor of Hubbard's office, he looked like a splendid antique himself. Who could imagine that passion had ever convulsed that thin white face, that those frail white fingers had ever curved in love and in hate? Age beyond the reach of most men had blanched this once-passionate man to a chill, ivory shadow.

For once, Hubbard felt glad—almost—that he himself was ineligible for the longevity treatment. The allotted five score and ten was enough for any except the very selfish—or selfless—man.

But Shortmire was answering his question. "I have no idea what the boy is like; I've never seen him." Then he added, "I suppose you've been wondering why I finally decided to make a will?"

"A lawyer never wonders when people do make wills, Jan," Hubbard said mildly. "He wonders when they don't."

"I'm going on a trip to Morethis. Only one of the colonized planets I've never visited." Shortmire's smile did not reach his amber-hard eyes. "Civilized planets, I should have said. It isn't official government policy to colonize planets that have intelligent native live-forms."

Not even the most besotted idealist could ever have described Jan Shortmire as altruistic. And for him to be concerned about Morethis, of all planets—Morethis, where the indigenous life-forms were such as to justify a ruthless colonization policy ... it was outrageous! True, the terrestrial government had been more generous toward the Morethans than toward any of the seven other intelligent life-forms they had found. But this tolerance was based wholly on fear—fear of these remnants of an old, old civilization, eking out their existence around a dying star, yet with terrible glories to remember in their twilight—and traces of these glories to protect them.

How was it that Shortmire, who had been everywhere, seen everything, had never been to Morethis? Hubbard looked keenly at his client. "What is all this, Jan?"

The old man shrugged. "Merely that the Foreign Office has suggested it would be wise for travelers to make a will before going there. Being a dutiful citizen of Earth, I comply." He smiled balefully.

"The Foreign Office has suggested that it would be wiser not to go at all," Hubbard said. "There are people who say Morethis ought to be fumigated completely."

"Ah, but it has rare and precious metals on which our industries depend. There are herbs which have multiplied the miracles of modern medicine, jewels and furs unmatched anywhere. We need the native miners and farmers and trappers to get these things for us."

"We could get them for ourselves. We do on the other planets."

Shortmire grinned. "On Morethis, somehow, our people can't seem to find these things themselves. Or, if they do, we can't find our people afterward. Which is why there is peace and friendship between Morethis and Earth."

"Friendship! Everyone knows the Morethans hate terrestrials. They tolerate us only because we're stronger!"

"Stronger physically." Shortmire's smile was fading. "Even technology is a kind of physical strength."

New apprehension took shape in Hubbard. "You're not going metaphysical in your old age, are you, Jan? And even if you are," he said quickly, while he was still innocent of knowledge, hence could not be consciously offending the other man's beliefs, "what a cult to choose! Blood, terror and torture!"

Shortmire grinned again. "You've been watching vidicasts, Peter. They've laid it on so thick, I'll probably find Morethis deadly dull rather than just ... deadly."

Certainly, all Hubbard knew of Morethis was based on hearsay evidence, but this was not a court of law. "Jan you're a fool! A third of the terrestrials who go to Morethis never come back, and mostly they're young men, strong men."

"Then they're the fools." Shortmire's voice was low and tired. "Because they're risking a whole lifetime, whereas all I'll be risking is a few years of a very boring existence."

Hubbard said no more. Even though the law still did not condone it, a man had the right to dispose of his own life as he saw fit.

Shortmire stood up. Barely stooped by age, he looked, with his great height and extreme emaciation, almost like a fasting saint—a ludicrous simile. "My wine palate is gone, Peter," he said, clapping the younger old man's shoulder, "women and I seem to have lost our mutual attraction, and I never did have much of a singing voice. At least this is one experience I'm not too old to savor."

"Death, do you mean?" Hubbard asked bluntly. "Or Morethis?"

Shortmire smiled. "Perhaps both."

So Peter Hubbard was not surprised when, a few months later, he got word that Jan Shortmire had died on Morethis. The surprising thing was the extraordinarily prosaic manner of his death: he had simply fallen into a river and drowned. No traveler on Morethis had been known to die by undisputed accident before; as a result, the vidicasts devoted more attention to the event than they might have otherwise. But the news died down, as other news took its place. In so large a universe, something was always happening; the dog days were forever gone from journalism.

Going through the old man's papers in his capacity as executor, Hubbard came across an old passport. He was startled to discover that this trip had not been Shortmire's first to Morethis. Why had he lied about it? But that was a question that no one alive could answer—or so Hubbard thought.

Almost two years went by before the will was finally probated on all the planets where Shortmire had owned property. Then the search for Emrys Shortmire began. Messages were dispatched to all the civilized planets, and Peter Hubbard settled back for a long wait.

Five years after Jan Shortmire's death, the intercom on Peter Hubbard's desk buzzed and his secretary's voice—his was one of the few legal offices wealthy enough to afford human help—said, "Mr. Emrys Shortmire to see you, sir."

How could a man come from so many light-years' distance without radioing on ahead, or at least tele-calling from his hotel? Dignity demanded that Hubbard tell his secretary to inform Shortmire that he never saw anyone without an appointment. Curiosity won. "Ask him to come in," he said.

The door slid open. Hubbard started to rise, with the old-fashioned courtesy of a family lawyer. But he never made it. He sat, frozen with shock, staring at the man in the doorway. Because Emrys Shortmire wasn't a man; he was a boy. He might have been a stripling of thirty, except for his eyes. Copper-bright and copper-hard they were, too hard for a boy's. Give him forty, even forty-five, that would still have made Jan Shortmire a father when he was nearly a hundred and twenty. The longevity treatment produced remarkable results, but none that fantastic. Though health and strength could be restored, fertility, like youth, once vanished was gone forever.

Yet the boy looked too sophisticated to have made a stupid mistake like that, if he were an imposter. More important, he looked like Jan Shortmire—not the Shortmire whom Hubbard had known, but the broad-shouldered youth of the early pictures, golden of hair and skin and eyes, almost classical in feature and build. Plastic surgery could have converted a fleeting resemblance to a precise one, yet, somehow, Hubbard felt that this was flesh and blood of the old man's.

"You're very like your father," he said, inaccurately: Emrys was less like his father than he should have been, given that startling identity of physique.

"Am I?" The boy smiled. "I never knew him. Of course, I know I look like the pictures, but pictures never tell much, do they?"

He had many papers to give Peter Hubbard. Too many; no honest man had his life so well in order. But then Emrys' honesty was not the issue, only his identity. The birth certificate said he had been born on Clergal fifty-five years before, so he was ten years older than Hubbard's wildest estimate. A young man, but not a boy—a man of full maturity, but still too young to be, normally, Jan Shortmire's son. Then Hubbard opened Emrys Shortmire's passport and received another shock.

He tried to sound calm. "I see you were on Morethis the same time your father was!"

Emrys' smile widened. "Curious coincidence, wasn't it?"

A surge of almost physical dislike filled the lawyer. "Is that all it was—a coincidence?"

"Are you suggesting that I pushed my father into the Ekkan?" Emrys asked pleasantly.

"Certainly not!" Hubbard was indignant at the thought that he, as a lawyer, would have voiced such a suspicion, even if it had occurred to him. "I thought you two might have arranged to meet on Morethis."

"I told you I'd never seen my father," Emrys reminded him. "As for what I was doing on Morethis—that's my business."

"All I'm concerned with is whether or not you are Emrys Shortmire." Distaste was almost tangible on Hubbard's tongue. "It does seem surprising that, since you were on Morethis at the time your father died, you should not have come to claim your inheritance sooner."

"I had affairs of my own to wind up," Emrys said flatly.

Hubbard tapped the papers. "You understand that these must be checked before you receive your father's estate?"

"I understand perfectly." Emrys' voice was soft as a Si-yllan cat-man's, and even more insulting. "They will be gone over thoroughly for any possible error, any tiny imperfection, anything that could invalidate my claim. But you will find them entirely in order."

"I'm sure of that." And Hubbard knew, if the papers were forgeries, they would be works of art.

"You'll probably want me to undergo an equally thorough physical examination for signs of—ah—surgical tampering. Yes, I see I'm right."

Ungenerous hope leaped inside Hubbard. "You would object?"

"On the contrary, I'd be delighted. Haven't had a thorough medical checkup for years." On this cooperative note, Emrys Shortmire bowed and left.

Hubbard sighed back against the velvet cushions of his chair—real silk, for he was a very rich old man. Unfortunately, he could not doubt that this was Jan Shortmire's progeny. But—and Hubbard sat upright—no matter how much Emrys resembled his father, that was only one parent. Who had the young man's mother been?

Quickly, Hubbard searched through the papers for the birth certificate. The

Comments (0)