Backlash by Winston K. Marks (classic literature books txt) 📗

- Author: Winston K. Marks

Book online «Backlash by Winston K. Marks (classic literature books txt) 📗». Author Winston K. Marks

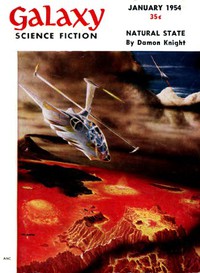

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction January 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I still feel that the ingratiating little runts never intended any harm. They were eager to please, a cinch to transact business with, and constantly, everlastingly grateful to us for giving them asylum.

Yes, we gave the genuflecting little devils asylum. And we were glad to have them around at first—especially when they presented our women with a gift to surpass all gifts: a custom-built domestic servant.

In a civilization that had made such a fetish of personal liberty and dignity, you couldn't hire a butler or an upstairs maid for less than love and money. And since love was pretty much rationed along the lines of monogamy, domestic service was almost a dead occupation. That is, until the Ollies came to our planet to stay.

Eventually I learned to despise the spineless little immigrants from Sirius, but the first time I met one he made me feel foolishly important. I looked at his frail, olive-skinned little form, and thought, If this is what space has to offer in the way of advanced life-forms ... well, we haven't done so badly on old Mother Earth.

This one's name was Johnson. All of them, the whole fifty-six, took the commonest Earth family names they could find, and dropped their own name-designations whose slobbering sibilance made them difficult for us to pronounce and write. It seemed strange, their casually wiping out their nominal heritage just for the sake of our convenience—imagine an O'Toole or a Rockefeller or an Adams arriving on Sirius IV and no sooner learning the local lingo than insisting on becoming known as Sslyslasciff-soszl!

But that was the Ollie. Anything to get along and please us. And of course, addressing them as Johnson, Smith, Jones, etc., did work something of a semantic protective coloration and reduce some of the barriers to quick adjustment to the aliens.

Johnson—Ollie Johnson—appeared at my third under-level office a few months after the big news of their shipwreck landing off the Maine coast. He arrived a full fifteen minutes ahead of his appointment, and I was too curious to stand on the dignity of office routine and make him wait.

As he stood in the doorway of my office, my first visual impression was of an emaciated adolescent, seasick green, prematurely balding.

He bowed, and bowed again, and spent thirty seconds reminding me that it was he who had sought the interview, and it was he who had the big favors to ask—and it was wonderful, gracious, generous I who flavored the room with the essence of mystery, importance, godliness and overpowering sweetness upon whose fragrance little Ollie Johnson had come to feast his undeserving senses.

"Sit down, sit down," I told him when I had soaked in all the celestial flattery I could hold. "I love you to pieces, too, but I'm curious about this proposition you mentioned in your message."

He eased into the chair as if it were much too good for him. He was strictly humanoid. His four-and-a-half-foot body was dressed in the most conservative Earth clothing, quiet colors and cheap quality.

While he swallowed slowly a dozen times, getting ready to outrage my illustrious being with his sordid business proposition, his coloring varied from a rather insipid gray-green to a rich olive—which is why the press instantly had dubbed them Ollies. When they got excited and blushed, they came close to the color of a ripe olive; and this was often.

Ollie Johnson hissed a few times, his equivalent of throat-clearing, and then lunged into his subject at a 90 degree tangent:

"Can it be that your gracious agreement to this interview connotes a willingness to traffic with us of the inferior ones?" His voice was light, almost reedy.

"If it's legal and there's a buck in it, can't see any reason why not," I told him.

"You manufacture and distribute devices, I am told. Wonderful labor-saving mechanisms that make life on Earth a constant pleasure."

I was almost tempted to hire him for my public relations staff.

"We do," I admitted. "Servo-mechanisms, appliances and gadgets of many kinds for the home, office and industry."

"It is to our everlasting disgrace," he said with humility, "that we were unable to salvage the means to give your magnificent civilization the worthy gift of our space drive. Had Flussissc or Shascinssith survived our long journey, it would be possible, but—" He bowed his head, as if waiting for my wrath at the stale news that the only two power-mechanic scientists on board were D.O.A.

"That was tough," I said. "But what's on your mind now?"

He raised his moist eyes, grateful at my forgiveness. "We who survived do possess a skill that might help repay the debt which we have incurred in intruding upon your glorious planet."

He begged my permission to show me something in the outer waiting room. With more than casual interest, I assented.

He moved obsequiously to the door, opened it and spoke to someone beyond my range of vision. His words sounded like a repetition of "sissle-flissle." Then he stepped aside, fastened his little wet eyes on me expectantly, and waited.

Suddenly the doorway was filled, jamb to jamb, floor to arch, with a hulking, bald-headed character with rugged pink features, a broad nose like a pug, and huge sugar-scoops for ears. He wore a quiet business suit of fine quality, obviously tailored to his six-and-a-half-foot, cliff-like physique. In spite of his bulk, he moved across the carpet to my desk on cat feet, and came to a halt with pneumatic smoothness.

"I am a Soth," he said in a low, creamy voice. It was so resonant that it seemed to come from the walls around us. "I have learned your language and your ways. I can follow instructions, solve simple problems and do your work. I am very strong. I can serve you well."

The recitation was an expressionless monotone that sounded almost haughty compared to the self-effacing Ollie's piping whines. His face had the dignity of a rock, and his eyes the quiet peace of a cool, deep mountain lake.

The Ollie came forward. "We have been able to repair only one of the six Soths we had on the ship. They are more fragile than we humanoids."

"They don't look it," I said. "And what do you mean by you humanoids? What's he?"

"You would call him—a robot, I believe."

My astonished reaction must have satisfied the Ollie, because he allowed his eyes to leave me and seek the carpet again, where they evidently were more comfortable.

"You mean you—you make these people?" I gasped.

He nodded. "We can reproduce them, given materials and facilities. Of course, your own robots must be vastly superior—" a hypocritical sop to my vanity—"but still we hope you may find a use for the Soths."

I got up and walked around the big lunker, trying to look blas�. "Well, yes," I lied. "Our robots probably have considerably better intellectual abilities—our cybernetic units, that is. However, you do have something in form and mobility."

That was the understatement of my career.

I finally pulled my face together, and said as casually as I could, "Would you like to license us to manufacture these—Soths?"

The Ollie fluttered his hands. "But that would require our working and mingling with your personnel," he said. "We wouldn't consider imposing in such a gross manner."

"No imposition at all," I assured him.

But he would have none of it: "We have studied your economics and have found that your firm is an outstanding leader in what you term 'business.' You have a superb distribution organization. It is our intention to offer you the exclusive—" he hesitated, then dragged the word from his amazing vocabulary—"franchise for the sale of our Soths. If you agree, we will not burden you with their manufacture. Our own little plant will produce and ship. You may then place them with your customers."

I studied the magnificent piece of animated sculpturing, stunned at the possibilities. "You say a Soth is strong. How strong?"

The huge creature startled me by answering the question himself. He bent flowingly from the waist, gripped my massive steel desk by one of its thick, overlapping top edges, and raised it a few inches from the floor—with the fingers of one hand. When he put it down, I stood up and hefted one edge myself. By throwing my back into it, I could just budge one side of the clumsy thing—four hundred pounds if it was an ounce!

Ollie Johnson modestly refrained from comment. He said, "The Department of Commerce has been helpful. They have explained your medium of exchange, and have helped us with the prices of raw materials. It was they who recommended your firm as a likely distributor."

"Have you figured how much one of these Soths should sell for?"

"We think we can show a modest profit if we sell them to you for $1200," he said. "Perhaps we can bring down our costs, if you find a wide enough demand for them."

I had expected ten or twenty times that figure. I'm afraid I got a little eager. "I—uh—shall we see if we can't just work out a little contract right now? Save you another trip back this afternoon."

"If you will forgive our boorish presumption," Ollie said, fumbling self-consciously in his baggy clothing, "I have already prepared such a document with the help of the Attorney General. A very kindly gentleman."

It was simple and concise. It allowed us to resell the Soths at a price of $2000, Fair Traded, giving us a gross margin of $800 to work with. He assured me that upkeep and repairs on the robot units were negligible, and we could extend a very generous warranty which the Ollies would make good in the event of failure. He gave me a quick rundown on the care and feeding of a Sirian Soth, and then jolted me with:

"There is just a single other favor I beg of you. Would you do my little colony the exquisite honor of accepting this Soth as your personal servant, Mr. Collins?"

"Servant?"

He bobbed his head. "Yes, sir. We have trained him in the rudiments of the household duties and conventions of your culture. He learns rapidly and never forgets an instruction. Your wife would find Soth most useful, I am quite certain."

"A magnificent specimen like this doing housework?" I marveled at the little creature's empty-headedness.

"Again I must beg your pardon, sir. I overlooked mentioning a suggestion by the Secretary of Labor that the Soths be sold only for use in domestic service. It was also the consensus of the President's whole cabinet that the economy of any nation could not cope with the problem of unemployment were our Soths to be made available for all the types of work for which they are fitted."

My dream of empire collapsed. The little green fellow was undoubtedly telling the truth. The unions would strike any plant or facility in the world where a Soth put foot on the job. It would ruin our retail consumer business, too—Soths wouldn't consume automobiles, copters, theater tickets and filets mignon.

"Yes, Mr. Johnson," I sighed. "I'll be happy to try out your Soth. We have a place out in the country where he'll come in handy."

The Ollie duly expressed his ecstasy at my decision, and backed out of my office waving his copy of the contract. I had assured him that our board of directors would meet within a week and confirm my signature.

I looked up at the hairless giant. As general director of the Home Appliance Division of Worldwide Machines, Incorporated, I had made a deal, all right. The first interplanetary business deal in history.

But for some reason, I couldn't escape the feeling that I'd been had.

On the limoucopter, they charged me double fare for Soth's transportation to the private field where I kept my boat. As we left Detroit, I watched him stare down at the flattened skyline, but he did it with the unseeing expression of an old commuter.

Jack, my personal pilot, had eyed my passenger at the airport with some concern and sullen muttering. Now he made much of trimming ship after takeoff. The boat did seem logy with the unaccustomed ballast—it was a four-passenger Arrow, built for speed, and Soth had to crouch and spread all over the two rear seats. But he did so without complaint or comment for the half-hour hop up to

Comments (0)