The Spy in the Elevator by Donald E. Westlake (a court of thorns and roses ebook free txt) 📗

- Author: Donald E. Westlake

Book online «The Spy in the Elevator by Donald E. Westlake (a court of thorns and roses ebook free txt) 📗». Author Donald E. Westlake

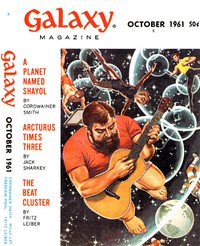

By DONALD E. WESTLAKE

Illustrated by WEST

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine October 1961.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

He was dangerously insane. He threatened

to destroy everything that was noble and

decent—including my date with my girl!

When the elevator didn't come, that just made the day perfect. A broken egg yolk, a stuck zipper, a feedback in the aircon exhaust, the window sticking at full transparency—well, I won't go through the whole sorry list. Suffice it to say that when the elevator didn't come, that put the roof on the city, as they say.

It was just one of those days. Everybody gets them. Days when you're lucky in you make it to nightfall with no bones broken.

But of all times for it to happen! For literally months I'd been building my courage up. And finally, just today, I had made up my mind to do it—to propose to Linda. I'd called her second thing this morning—right after the egg yolk—and invited myself down to her place. "Ten o'clock," she'd said, smiling sweetly at me out of the phone. She knew why I wanted to talk to her. And when Linda said ten o'clock, she meant ten o'clock.

Don't get me wrong. I don't mean that Linda's a perfectionist or a harridan or anything like that. Far from it. But she does have a fixation on that one subject of punctuality. The result of her job, of course. She was an ore-sled dispatcher. Ore-sleds, being robots, were invariably punctual. If an ore-sled didn't return on time, no one waited for it. They simply knew that it had been captured by some other Project and had blown itself up.

Well, of course, after working as an ore-sled dispatcher for three years, Linda quite naturally was a bit obsessed. I remember one time, shortly after we'd started dating, when I arrived at her place five minutes late and found her having hysterics. She thought I'd been killed. She couldn't visualize anything less than that keeping me from arriving at the designated moment. When I told her what actually had happened—I'd broken a shoe lace—she refused to speak to me for four days.

And then the elevator didn't come.

Until then, I'd managed somehow to keep the day's minor disasters from ruining my mood. Even while eating that horrible egg—I couldn't very well throw it away, broken yolk or no; it was my breakfast allotment and I was hungry—and while hurriedly jury-rigging drapery across that gaspingly transparent window—one hundred and fifty-three stories straight down to slag—I kept going over and over my prepared proposal speeches, trying to select the most effective one.

I had a Whimsical Approach: "Honey, I see there's a nice little Non-P apartment available up on one seventy-three." And I had a Romantic Approach: "Darling, I can't live without you at the moment. Temporarily, I'm madly in love with you. I want to share my life with you for a while. Will you be provisionally mine?" I even had a Straightforward Approach: "Linda, I'm going to be needing a wife for at least a year or two, and I can't think of anyone I would rather spend that time with than you."

Actually, though I wouldn't even have admitted this to Linda, much less to anyone else, I loved her in more than a Non-P way. But even if we both had been genetically desirable (neither of us were) I knew that Linda relished her freedom and independence too much to ever contract for any kind of marriage other than Non-P—Non-Permanent, No Progeny.

So I rehearsed my various approaches, realizing that when the time came I would probably be so tongue-tied I'd be capable of no more than a blurted, "Will you marry me?" and I struggled with zippers and malfunctioning air-cons, and I managed somehow to leave the apartment at five minutes to ten.

Linda lived down on the hundred fortieth floor, thirteen stories away. It never took more than two or three minutes to get to her place, so I was giving myself plenty of time.

But then the elevator didn't come.

I pushed the button, waited, and nothing happened. I couldn't understand it.

The elevator had always arrived before, within thirty seconds of the button being pushed. This was a local stop, with an elevator that traveled between the hundred thirty-third floor and the hundred sixty-seventh floor, where it was possible to make connections for either the next local or for the express. So it couldn't be more than twenty stories away. And this was a non-rush hour.

I pushed the button again, and then I waited some more. I looked at my watch and it was three minutes to ten. Two minutes, and no elevator! If it didn't arrive this instant, this second, I would be late.

It didn't arrive.

I vacillated, not knowing what to do next. Stay, hoping the elevator would come after all? Or hurry back to the apartment and call Linda, to give her advance warning that I would be late?

Ten more seconds, and still no elevator. I chose the second alternative, raced back down the hall, and thumbed my way into my apartment. I dialed Linda's number, and the screen lit up with white letters on black: PRIVACY DISCONNECTION.

Of course! Linda expected me at any moment. And she knew what I wanted to say to her, so quite naturally she had disconnected the phone, to keep us from being interrupted.

Frantic, I dashed from the apartment again, back down the hall to the elevator, and leaned on that blasted button with all my weight. Even if the elevator should arrive right now, I would still be almost a minute late.

No matter. It didn't arrive.

I would have been in a howling rage anyway, but this impossibility piled on top of all the other annoyances and breakdowns of the day was just too much. I went into a frenzy, and kicked the elevator door three times before I realized I was hurting myself more than I was hurting the door. I limped back to the apartment, fuming, slammed the door behind me, grabbed the phone book and looked up the number of the Transit Staff. I dialed, prepared to register a complaint so loud they'd be able to hear me in sub-basement three.

I got some more letters that spelled: BUSY.

It took three tries before I got through to a hurried-looking female receptionist "My name is Rice!" I bellowed. "Edmund Rice! I live on the hundred and fifty-third floor! I just rang for the elevator and——"

"The-elevator-is-disconnected." She said it very rapidly, as though she were growing very used to saying it.

It only stopped me for a second. "Disconnected? What do you mean disconnected? Elevators don't get disconnected!" I told her.

"We-will-resume-service-as-soon-as-possible," she rattled. My bellowing was bouncing off her like radiation off the Project force-screen.

I changed tactics. First I inhaled, making a production out of it, giving myself a chance to calm down a bit. And then I asked, as rationally as you could please, "Would you mind terribly telling me why the elevator is disconnected?"

"I-am-sorry-sir-but-that——"

"Stop," I said. I said it quietly, too, but she stopped. I saw her looking at me. She hadn't done that before, she'd merely gazed blankly at her screen and parroted her responses.

But now she was actually looking at me.

I took advantage of the fact. Calmly, rationally, I said to her, "I would like to tell you something, Miss. I would like to tell you just what you people have done to me by disconnecting the elevator. You have ruined my life."

She blinked, open-mouthed. "Ruined your life?"

"Precisely." I found it necessary to inhale again, even more slowly than before. "I was on my way," I explained, "to propose to a girl whom I dearly love. In every way but one, she is the perfect woman. Do you understand me?"

She nodded, wide-eyed. I had stumbled on a romantic, though I was too preoccupied to notice it at the time.

"In every way but one," I continued. "She has one small imperfection, a fixation about punctuality. And I was supposed to meet her at ten o'clock. I'm late!" I shook my fist at the screen. "Do you realize what you've done, disconnecting the elevator? Not only won't she marry me, she won't even speak to me! Not now! Not after this!"

"Sir," she said tremulously, "please don't shout."

"I'm not shouting!"

"Sir, I'm terribly sorry. I understand your—"

"You understand?" I trembled with speechless fury.

She looked all about her, and then leaned closer to the screen, revealing a cleavage that I was too distraught at the moment to pay any attention to. "We're not supposed to give this information out, sir," she said, her voice low, "but I'm going to tell you, so you'll understand why we had to do it. I think it's perfectly awful that it had to ruin things for you this way. But the fact of the matter is—" she leaned even closer to the screen—"there's a spy in the elevator."

II

It was my turn to be stunned.

I just gaped at her. "A—a what?"

"A spy. He was discovered on the hundred forty-seventh floor, and managed to get into the elevator before the Army could catch him. He jammed it between floors. But the Army is doing everything it can think of to get him out."

"Well—but why should there be any problem about getting him out?"

"He plugged in the manual controls. We can't control the elevator from outside at all. And when anyone tries to get into the shaft, he aims the elevator at them."

That sounded impossible. "He aims the elevator?"

"He runs it up and down the shaft," she explained, "trying to crush anybody who goes after him."

"Oh," I said. "So it might take a while."

She leaned so close this time that even I, distracted as I was, could hardly help but take note of her cleavage. She whispered, "They're afraid they'll have to starve him out."

"Oh, no!"

She nodded solemnly. "I'm terribly sorry, sir," she said. Then she glanced to her right, suddenly straightened up again, and said, "We-will-resume-service-as-soon-as-possible." Click. Blank screen.

For a minute or two, all I could do was sit and absorb what I'd been told. A spy in the elevator! A spy who had managed to work his way all the way up to the hundred forty-seventh floor before being unmasked!

What in the world was the matter with the Army? If things were getting that lax, the Project was doomed, force-screen or no. Who knew how many more spies there were in the Project, still unsuspected?

Until that moment, the state of siege in which we all lived had had no reality for me. The Project, after all, was self-sufficient and completely enclosed. No one ever left, no one ever entered. Under our roof, we were a nation, two hundred stories high. The ever-present threat of other projects had never been more for me—or for most other people either, I suspected—than occasional ore-sleds that didn't return, occasional spies shot down as they tried to sneak into the building, occasional spies of our own leaving the Project in tiny radiation-proof cars, hoping to get safely within another project and bring back news of any immediate threats and dangers that project might be planning for us. Most spies didn't return; most ore-sleds did. And within the Project life was full, the knowledge of external dangers merely lurking at the backs of our minds. After all, those external dangers had been no more than potential for decades, since what Dr. Kilbillie called the Ungentlemanly Gentleman's War.

Dr. Kilbillie—Intermediate Project History, when I was fifteen years old—had private names for every major war of the twentieth century. There was the Ignoble Nobleman's War, the Racial Non-Racial War, and the Ungentlemanly Gentleman's War, known to the textbooks of course as World Wars One, Two, and Three.

The rise of the Projects, according to Dr. Kilbillie, was the result of many many factors, but two of the most important were the population explosion and the Treaty of Oslo. The population explosion, of course, meant that there was continuously more and more people but never any more space. So that housing, in the historically short time of one century, made a complete transformation from horizontal expansion to vertical. Before 1900, the vast majority of human beings lived in tiny huts of from one to five stories. By 2000, everybody lived in Projects. From the very beginning, small attempts were made to make these Projects more than dwelling places. By mid-century, Projects (also called apartments and co-ops) already included

Comments (0)