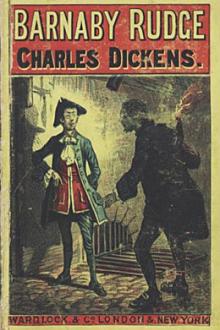

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗

- Author: Charles Dickens

Book online «Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗». Author Charles Dickens

‘Here!’ he hoarsely cried, appearing from the darkness; out of breath, and blackened with the smoke. ‘We have done all we can; the fire is burning itself out; and even the corners where it hasn’t spread, are nothing but heaps of ruins. Disperse, my lads, while the coast’s clear; get back by different ways; and meet as usual!’ With that, he disappeared again,—contrary to his wont, for he was always first to advance, and last to go away,—leaving them to follow homewards as they would.

It was not an easy task to draw off such a throng. If Bedlam gates had been flung wide open, there would not have issued forth such maniacs as the frenzy of that night had made. There were men there, who danced and trampled on the beds of flowers as though they trod down human enemies, and wrenched them from the stalks, like savages who twisted human necks. There were men who cast their lighted torches in the air, and suffered them to fall upon their heads and faces, blistering the skin with deep unseemly burns. There were men who rushed up to the fire, and paddled in it with their hands as if in water; and others who were restrained by force from plunging in, to gratify their deadly longing. On the skull of one drunken lad—not twenty, by his looks—who lay upon the ground with a bottle to his mouth, the lead from the roof came streaming down in a shower of liquid fire, white hot; melting his head like wax. When the scattered parties were collected, men—living yet, but singed as with hot irons—were plucked out of the cellars, and carried off upon the shoulders of others, who strove to wake them as they went along, with ribald jokes, and left them, dead, in the passages of hospitals. But of all the howling throng not one learnt mercy from, or sickened at, these sights; nor was the fierce, besotted, senseless rage of one man glutted.

Slowly, and in small clusters, with hoarse hurrahs and repetitions of their usual cry, the assembly dropped away. The last few red-eyed stragglers reeled after those who had gone before; the distant noise of men calling to each other, and whistling for others whom they missed, grew fainter and fainter; at length even these sounds died away, and silence reigned alone.

Silence indeed! The glare of the flames had sunk into a fitful, flashing light; and the gentle stars, invisible till now, looked down upon the blackening heap. A dull smoke hung upon the ruin, as though to hide it from those eyes of Heaven; and the wind forbore to move it. Bare walls, roof open to the sky—chambers, where the beloved dead had, many and many a fair day, risen to new life and energy; where so many dear ones had been sad and merry; which were connected with so many thoughts and hopes, regrets and changes—all gone. Nothing left but a dull and dreary blank—a smouldering heap of dust and ashes—the silence and solitude of utter desolation.

Chapter 56

The Maypole cronies, little dreaming of the change so soon to come upon their favourite haunt, struck through the Forest path upon their way to London; and avoiding the main road, which was hot and dusty, kept to the by-paths and the fields. As they drew nearer to their destination, they began to make inquiries of the people whom they passed, concerning the riots, and the truth or falsehood of the stories they had heard. The answers went far beyond any intelligence that had spread to quiet Chigwell. One man told them that that afternoon the Guards, conveying to Newgate some rioters who had been re-examined, had been set upon by the mob and compelled to retreat; another, that the houses of two witnesses near Clare Market were about to be pulled down when he came away; another, that Sir George Saville’s house in Leicester Fields was to be burned that night, and that it would go hard with Sir George if he fell into the people’s hands, as it was he who had brought in the Catholic bill. All accounts agreed that the mob were out, in stronger numbers and more numerous parties than had yet appeared; that the streets were unsafe; that no man’s house or life was worth an hour’s purchase; that the public consternation was increasing every moment; and that many families had already fled the city. One fellow who wore the popular colour, damned them for not having cockades in their hats, and bade them set a good watch to-morrow night upon their prison doors, for the locks would have a straining; another asked if they were fire-proof, that they walked abroad without the distinguishing mark of all good and true men;—and a third who rode on horseback, and was quite alone, ordered them to throw each man a shilling, in his hat, towards the support of the rioters. Although they were afraid to refuse compliance with this demand, and were much alarmed by these reports, they agreed, having come so far, to go forward, and see the real state of things with their own eyes. So they pushed on quicker, as men do who are excited by portentous news; and ruminating on what they had heard, spoke little to each other.

It was now night, and as they came nearer to the city they had dismal confirmation of this intelligence in three great fires, all close together, which burnt fiercely and were gloomily reflected in the sky. Arriving in the immediate suburbs, they found that almost every house had chalked upon its door in large characters ‘No Popery,’ that the shops were shut, and that alarm and anxiety were depicted in every face they passed.

Noting these things with a degree of apprehension which neither of the three cared to impart, in its full extent, to his companions, they came to a turnpike-gate, which was shut. They were passing through the turnstile on the path, when a horseman rode up from London at a hard gallop, and called to the toll-keeper in a voice of great agitation, to open quickly in the name of God.

The adjuration was so earnest and vehement, that the man, with a lantern in his hand, came running out—toll-keeper though he was—and was about to throw the gate open, when happening to look behind him, he exclaimed, ‘Good Heaven, what’s that! Another fire!’

At this, the three turned their heads, and saw in the distance—straight in the direction whence they had come—a broad sheet of flame, casting a threatening light upon the clouds, which glimmered as though the conflagration were behind them, and showed like a wrathful sunset.

‘My mind misgives me,’ said the horseman, ‘or I know from what far building those flames come. Don’t stand aghast, my good fellow. Open the gate!’

‘Sir,’ cried the man, laying his hand upon his horse’s bridle as he let him through: ‘I know you now, sir; be advised by me; do not go on. I saw them pass, and know what kind of men they are. You will be murdered.’

‘So be it!’ said the horseman, looking intently towards the fire, and not at him who spoke.

‘But sir—sir,’ cried the man, grasping at his rein more tightly yet, ‘if you do go on, wear the blue riband. Here, sir,’ he added, taking one from his own hat, ‘it’s necessity, not choice, that makes me wear it; it’s

Comments (0)