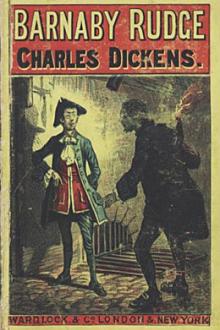

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗

- Author: Charles Dickens

Book online «Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty by Charles Dickens (uplifting book club books txt) 📗». Author Charles Dickens

‘Do!’ cried the three friends, pressing round his horse. ‘Mr Haredale—worthy sir—good gentleman—pray be persuaded.’

‘Who’s that?’ cried Mr Haredale, stooping down to look. ‘Did I hear Daisy’s voice?’

‘You did, sir,’ cried the little man. ‘Do be persuaded, sir. This gentleman says very true. Your life may hang upon it.’

‘Are you,’ said Mr Haredale abruptly, ‘afraid to come with me?’

‘I, sir?—N-n-no.’

‘Put that riband in your hat. If we meet the rioters, swear that I took you prisoner for wearing it. I will tell them so with my own lips; for as I hope for mercy when I die, I will take no quarter from them, nor shall they have quarter from me, if we come hand to hand to-night. Up here—behind me—quick! Clasp me tight round the body, and fear nothing.’

In an instant they were riding away, at full gallop, in a dense cloud of dust, and speeding on, like hunters in a dream.

It was well the good horse knew the road he traversed, for never once—no, never once in all the journey—did Mr Haredale cast his eyes upon the ground, or turn them, for an instant, from the light towards which they sped so madly. Once he said in a low voice, ‘It is my house,’ but that was the only time he spoke. When they came to dark and doubtful places, he never forgot to put his hand upon the little man to hold him more securely in his seat, but he kept his head erect and his eyes fixed on the fire, then, and always.

The road was dangerous enough, for they went the nearest way—headlong—far from the highway—by lonely lanes and paths, where waggon-wheels had worn deep ruts; where hedge and ditch hemmed in the narrow strip of ground; and tall trees, arching overhead, made it profoundly dark. But on, on, on, with neither stop nor stumble, till they reached the Maypole door, and could plainly see that the fire began to fade, as if for want of fuel.

‘Down—for one moment—for but one moment,’ said Mr Haredale, helping Daisy to the ground, and following himself. ‘Willet—Willet—where are my niece and servants—Willet!’

Crying to him distractedly, he rushed into the bar.—The landlord bound and fastened to his chair; the place dismantled, stripped, and pulled about his ears;—nobody could have taken shelter here.

He was a strong man, accustomed to restrain himself, and suppress his strong emotions; but this preparation for what was to follow—though he had seen that fire burning, and knew that his house must be razed to the ground—was more than he could bear. He covered his face with his hands for a moment, and turned away his head.

‘Johnny, Johnny,’ said Solomon—and the simple-hearted fellow cried outright, and wrung his hands—‘Oh dear old Johnny, here’s a change! That the Maypole bar should come to this, and we should live to see it! The old Warren too, Johnny—Mr Haredale—oh, Johnny, what a piteous sight this is!’

Pointing to Mr Haredale as he said these words, little Solomon Daisy put his elbows on the back of Mr Willet’s chair, and fairly blubbered on his shoulder.

While Solomon was speaking, old John sat, mute as a stock-fish, staring at him with an unearthly glare, and displaying, by every possible symptom, entire and complete unconsciousness. But when Solomon was silent again, John followed with his great round eyes the direction of his looks, and did appear to have some dawning distant notion that somebody had come to see him.

‘You know us, don’t you, Johnny?’ said the little clerk, rapping himself on the breast. ‘Daisy, you know—Chigwell Church—bell-ringer—little desk on Sundays—eh, Johnny?’

Mr Willet reflected for a few moments, and then muttered, as it were mechanically: ‘Let us sing to the praise and glory of—’

‘Yes, to be sure,’ cried the little man, hastily; ‘that’s it—that’s me, Johnny. You’re all right now, an’t you? Say you’re all right, Johnny.’

‘All right?’ pondered Mr Willet, as if that were a matter entirely between himself and his conscience. ‘All right? Ah!’

‘They haven’t been misusing you with sticks, or pokers, or any other blunt instruments—have they, Johnny?’ asked Solomon, with a very anxious glance at Mr Willet’s head. ‘They didn’t beat you, did they?’

John knitted his brow; looked downwards, as if he were mentally engaged in some arithmetical calculation; then upwards, as if the total would not come at his call; then at Solomon Daisy, from his eyebrow to his shoe-buckle; then very slowly round the bar. And then a great, round, leaden-looking, and not at all transparent tear, came rolling out of each eye, and he said, as he shook his head:

‘If they’d only had the goodness to murder me, I’d have thanked ‘em kindly.’

‘No, no, no, don’t say that, Johnny,’ whimpered his little friend. ‘It’s very, very bad, but not quite so bad as that. No, no!’

‘Look’ee here, sir!’ cried John, turning his rueful eyes on Mr Haredale, who had dropped on one knee, and was hastily beginning to untie his bonds. ‘Look’ee here, sir! The very Maypole—the old dumb Maypole—stares in at the winder, as if it said, “John Willet, John Willet, let’s go and pitch ourselves in the nighest pool of water as is deep enough to hold us; for our day is over!”’

‘Don’t, Johnny, don’t,’ cried his friend: no less affected with this mournful effort of Mr Willet’s imagination, than by the sepulchral tone in which he had spoken of the Maypole. ‘Please don’t, Johnny!’

‘Your loss is great, and your misfortune a heavy one,’ said Mr Haredale, looking restlessly towards the door: ‘and this is not a time to comfort you. If it were, I am in no condition to do so. Before I leave you, tell me one thing, and try to tell me plainly, I implore you. Have you seen, or heard of Emma?’

‘No!’ said Mr Willet.

‘Nor any one but these bloodhounds?’

‘No!’

‘They rode away, I trust in Heaven, before these dreadful scenes began,’ said Mr Haredale, who, between his agitation, his eagerness to mount his horse again, and the dexterity with which the cords were tied, had scarcely yet undone one knot. ‘A knife, Daisy!’

‘You didn’t,’ said John, looking about, as though he had lost his pocket-handkerchief, or some such slight article—‘either of you gentlemen—see a—a coffin anywheres, did you?’

‘Willet!’ cried Mr Haredale. Solomon dropped the knife, and instantly becoming limp from head to foot, exclaimed ‘Good gracious!’

‘—Because,’ said John, not at all regarding them, ‘a dead man called a little time ago, on his way yonder. I could have told you what name was on the plate, if he had brought his coffin with him, and left it behind. If he didn’t, it don’t signify.’

His landlord, who had listened to these words with breathless attention, started that moment to his feet; and, without a word, drew Solomon Daisy

Comments (0)