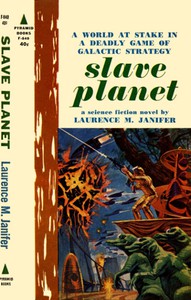

Slave Planet by Laurence M. Janifer (top 20 books to read txt) 📗

- Author: Laurence M. Janifer

Book online «Slave Planet by Laurence M. Janifer (top 20 books to read txt) 📗». Author Laurence M. Janifer

An act of this nature cannot be undertaken without grave thought and consideration. We affirm that such consideration has been given to this step.

It is needless to have fear as to the outcome of this action. No isolated world can stand against, not only the might, but the moral judgment of the Confederation. Arms can be used only as a last resort, but times will come in the history of peoples when they must be so used, when no other argument is sufficient to force one party to cease and desist from immoral and unbearable practices.

In accordance with the laws of the Confederation, no weapons shall be used which destroy planetary mass.

In general, Our efforts are directed toward as little blood-shed as possible. Our aim is to free the unfortunate native beings of Fruyling's World, and then to begin a campaign of re-education.

The fate of the human beings who have enslaved these natives shall be left to the Confederation Courts, which are competent to deal in such matters by statute of the year forty-seven of the Confederation. We pledge that We shall not interfere with such dealings by the Courts.

We may further reassure the peoples of the Confederation that no further special efforts on their part will be called for. This is not to be thought of as a war or even as a campaign, but merely as one isolated, regretted but necessary blow at a system which cannot but be a shock to the mind of civilized man.

That blow must be delivered, as We have been advised by Our Councillors. It shall be delivered.

The ships, leaving as directed, will approach Fruyling's World, leaving the FTL embodiments and re-entering the world-line, within ten days. Full reports will be available within one month.

In giving this directive, We have been mindful of the future status of any alien beings on worlds yet to be discovered. We hereby determine, for ourselves and our successors, that nowhere within reach of the Confederation may slavery exist, under any circumstances. The heritage of freedom which We have protected, and which belongs to all peoples, must be shared by all peoples everywhere, and to that end we direct Our actions, and Our prayers.

Given under date of May 21, in the year two hundred and ten of the Confederation, to be distributed and published everywhere within the Confederation, under Our hand and seal:

Richard Germont

by Grace of God Executive

of the Confederation

together with

His Council in judgment assembled

all members subscribing thereto.

The room had no windows.

There was an air-conditioning duct, but Cadnan did not know what such a thing was, nor would he have understood without lengthy and tiresome explanations. He didn't know he needed air to live: he knew only that the room was dark and that he was alone, boxed in, frightened. He guessed that somewhere, in another such room, Dara was waiting, just as frightened as he was, and that guess made him feel worse.

Somehow, he told himself, he would have to escape. Somehow he would have to get to Dara and save her from the punishment, so that she did not feel pain. It was wrong for Dara to feel pain.

But there was no way of escape. He had crept along the walls, pushing with his whole body in hopes of some opening. But the walls were metal and he could not push through metal. He could, in fact, do nothing at all except sit and wait for the punishment he knew was coming. He was sure, now, that it would be the great punishment, that he and Dara would be dead and no more. And perhaps, for his disobedience, he deserved death.

But Dara could not die.

He heard himself say her name, but his voice sounded strange and he barely recognized it. It seemed to be blotted up by the darkness. And after that, for a long time, he said nothing at all.

He thought suddenly of old Gornom, and of Puna. They had said there was an obedience in all things. The slaves obeyed, the masters obeyed, the trees obeyed. And, possibly, the chain of obedience, if not already broken by Marvor's escape and what he and Dara had tried to do, extended also to the walls of his dark room. For a long time he considered what that might mean.

If the walls obeyed, he might be able to tell them to go. They would move and he could leave and find Dara. Since it would not be for himself but for Dara, such a command might not count as an escape: the chain of obedience might work for him.

This complicated chain of reasoning occupied him for an agonized time before he finally determined to put it to the test. But, when he did, the walls did not move. The door, which he tried as soon as it occurred to him to do so, didn't move either. With a land of terror he told himself that the chain of obedience had been broken.

That thought was too terrible for him to contemplate for long, and he began to change it, little by little, in his mind. Perhaps (for instance) the chain was only broken for him and for Marvor: perhaps it still worked as well as ever for all those who still obeyed the rules. That was better: it kept the world whole, and sane, and reasonable. But along with it came the picture of Gornom, watching small Cadnan sadly. Cadnan felt a weight press down on him, and grow, and grow.

He tried the walls and the door again, almost mechanically. He felt his way around the room. There was nothing he could do. But that idea would not stay in his mind: there had to be something, and he had to find it. In a few seconds, he told himself, he would find it. He tried the walls again. He was beginning to shiver. In a few seconds, only a few seconds, he would find the way, and then....

The door opened, and he whirled and stared at it. The sudden light hurt his eye, but he closed it for no more than a second. As soon as he could he opened it again, and stood, too unsure of himself to move, watching the master framed in the doorway. It was the one who was called Dodd.

Dodd stared back for what seemed a long time. Cadnan said nothing, waiting and wondering.

"It's all right," the master said at last. "You don't have to be afraid, Cadnan. I'm not going to hurt you." He looked sadly at the slave, but Cadnan ignored the look: there was no room in him for more guilt.

"I am not afraid," he said. He thought of going past Dodd to find Dara, but perhaps Dodd had come to bring him to her. Perhaps Dodd knew where she was. He questioned the master with Dara's name.

"The female?" Dodd asked. "She's all right. She's in another room, just like this one. A solitary room."

Cadnan shook his head. "She must not stay there."

"You don't have to worry," Dodd said. "Nobody's doing anything to her. Not right now, anyhow. I—not right now."

"She must escape," Cadnan said, and Dodd's sadness appeared to grow. He pushed at the air as if he were trying to move it all away.

"She can't." His hands fell to his sides. "Neither can you, Cadnan. I'm—look, there's a guard stationed right down the corridor, watching this door every second I'm here. There are electronic networks in the door itself, so that if you manage somehow to open it there'll be an alarm." He paused, and began again, more slowly. "If you go past me, or if you get the door open, the noise will start again. You won't get fifteen feet."

Cadnan understood some of the speech, and ignored the rest: it wasn't important. Only one thing was important: "She can not die."

Dodd shook his head. "I'm sorry," he said flatly. "There's nothing I can do." A silence fell and, after a time, he broke it. "Cadnan, you've really messed things up. I know you're right—anybody knows it. Slavery—slavery is—well, look, whatever it is, the trouble is it's necessary. Here and now. Without you, without your people, we couldn't last on this world. We need you, Cadnan, whether it's right or not: and that has to come first."

Cadnan frowned. "I do not understand," he said.

"Doesn't matter," Dodd told him. "I can understand how you feel. We've treated you—pretty badly, I guess. Pretty badly." He looked away with what seemed nervousness. But there was nothing to see outside the door, nothing but the corridor light that spilled in and framed him.

"No," Cadnan said earnestly, still puzzled. "Masters are good. It is true. Masters are always good."

"You don't have to be afraid of me," Dodd said, still looking away. "Nothing I could do could hurt you now—even if I wanted to hurt you. And I don't, Cadnan. You know I don't."

"I am not afraid," Cadnan said. "I speak the truth, no more. Masters are good: it is a great truth."

Dodd turned to face him. "But you tried to escape."

Cadnan nodded. "Dara can not die," he said in a reasonable tone. "She would not go without me."

"Die?" Dodd asked, and then: "Oh. I see. The other—"

There was a long silence. Cadnan watched Dodd calmly. Dodd had turned again to stare out into the hallway, his hands nervously moving at his sides. Cadnan thought again of going past him, but then Dodd turned and spoke, his head low.

"I've got to tell you," he said. "I came here—I don't know why, but maybe I just came to tell you what's happening."

Cadnan nodded. "Tell me," he said, very calmly.

Dodd said: "I—" and then stopped. He reached for the door, held it for a second without closing it, and then, briefly, shook his head. "You're going to die," he said in an even, almost inhuman tone. "You're both going to die. For trying to escape. And the whole of your—clan, or family, or whatever that is—they're going to die with you. All of them." It was coming out in a single rush: Dodd's eyes fluttered closed. "It's my fault. It's our fault. We did it. We...."

And the rush stopped. Cadnan waited for a second, but there was no more. "Dara is not to die," he said.

Dodd sighed heavily, his eyes still closed. "I'm—sorry," he said slowly. "It's a silly thing to say: I'm sorry. I wish there was something I could do." He paused. "But there isn't. I wish—never mind. It doesn't matter. But you understand, don't you? You understand?"

Cadnan had room for only one thought, the most daring of his entire life. "You must get Dara away."

"I can't," Dodd said, unmoving.

Cadnan peered at him, half-fearfully. "You are a master." One did not give orders to masters, or argue with them.

But Dodd did not reach for punishment. "I can't," he said again. "If I help Dara, it's the jungle for me, or worse. And I can't live there. I need what's here. It's a matter of—a matter of necessity. Understand?" His eyes opened, bright and blind. "It's a matter of necessity," he said. "It has to be that way, and that's all."

Cadnan stared at him for a long second. He thought of Dara, thought of the punishment to come. The master had said there was nothing to do: but that thought was insupportable. There had to be something. There had to be a way....

There was a way.

Shouting: "Dara!" he found himself in the corridor, somehow having pushed past Dodd. He stood, turning, and saw another master with a punishment tube. Everything was still: there was no time for anything to move in.

He never knew if the tube had done it, or if Dodd had hit him from behind. Very suddenly, he knew nothing at all, and the world was blank, black, and distant. If time passed he knew nothing about it.

When he woke again he was alone again: he was back in the dark and solitary room.

17The office was dim now, at evening, but the figure behind the desk was rigid and unchanging, and the voice as singular as ever. "Do what you will," Dr. Haenlingen said. "I have always viewed love as the final aberration: it is the trap which lies in wait for the unwary sane. But no aberration is important, any more...."

"I'm trying to help him—" Norma began.

"You can't help him, child," Dr. Haenlingen said. Her eyes were closed: she looked as if she were preparing, at last, for death. "You feel too closely for him: you can't see him clearly enough to know what help he needs."

"But I've got to—"

"Nothing is predicated on necessity but action," Dr. Haenlingen said. "Certainly not success."

Norma went to the desk, leaned over it, looking down

Comments (0)