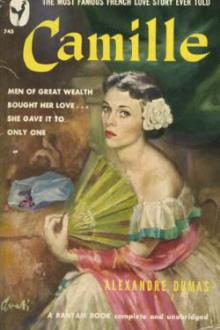

Camille - fils Alexandre Dumas (i have read the book a hundred times txt) 📗

- Author: fils Alexandre Dumas

- Performer: -

Book online «Camille - fils Alexandre Dumas (i have read the book a hundred times txt) 📗». Author fils Alexandre Dumas

“Thanks. Now tell me what it was she wanted to say to you last night.”

“Nothing at all. It was only to get rid of the count; but I have really something to see her about to-day, and I am bringing her an answer now.”

At this moment Marguerite reappeared from her dressing-room, wearing a coquettish little nightcap with bunches of yellow ribbons, technically known as “cabbages.” She looked ravishing. She had satin slippers on her bare feet, and was in the act of polishing her nails.

“Well,” she said, seeing Prudence, “have you seen the duke?”

“Yes, indeed.”

“And what did he say to you?”

“He gave me—”

“How much?”

“Six thousand.”

“Have you got it?”

“Yes.

“Did he seem put out?”

“No.”

“Poor man!”

This “Poor man!” was said in a tone impossible to render. Marguerite took the six notes of a thousand francs.

“It was quite time,” she said. “My dear Prudence, are you in want of any money?”

“You know, my child, it is the 15th in a couple of days, so if you could lend me three or four hundred francs, you would do me a real service.”

“Send over tomorrow; it is too late to get change now.”

“Don’t forget.”

“No fear. Will you have supper with us?”

“No, Charles is waiting for me.”

“You are still devoted to him?”

“Crazy, my dear! I will see you tomorrow. Goodbye, Armand.”

Mme. Duvernoy went out.

Marguerite opened the drawer of a side-table and threw the bank-notes into it.

“Will you permit me to get into bed?” she said with a smile, as she moved toward the bed.

“Not only permit, but I beg of you.”

She turned back the covering and got into bed.

“Now,” said she, “come and sit down by me, and let’s have a talk.”

Prudence was right: the answer that she had brought to Marguerite had put her into a good humour.

“Will you forgive me for my bad temper tonight?” she said, taking my hand.

“I am ready to forgive you as often as you like.”

“And you love me?”

“Madly.”

“In spite of my bad disposition?”

“In spite of all.”

“You swear it?”

“Yes,” I said in a whisper.

Nanine entered, carrying plates, a cold chicken, a bottle of claret, and some strawberries.

“I haven’t had any punch made,” said Nanine; “claret is better for you. Isn’t it, sir?”

“Certainly,” I replied, still under the excitement of Marguerite’s last words, my eyes fixed ardently upon her.

“Good,” said she; “put it all on the little table, and draw it up to the bed; we will help ourselves. This is the third night you have sat up, and you must be in want of sleep. Go to bed. I don’t want anything more.”

“Shall I lock the door?”

“I should think so! And above all, tell them not to admit anybody before midday.”

At five o’clock in the morning, as the light began to appear through the curtains, Marguerite said to me: “Forgive me if I send you away; but I must. The duke comes every morning; they will tell him, when he comes, that I am asleep, and perhaps he will wait until I wake.”

I took Marguerite’s head in my hands; her loosened hair streamed about her; I gave her a last kiss, saying: “When shall I see you again?”

“Listen,” she said; “take the little gilt key on the mantelpiece, open that door; bring me back the key and go. In the course of the day you shall have a letter, and my orders, for you know you are to obey blindly.”

“Yes; but if I should already ask for something?”

“What?”

“Let me have that key.”

“What you ask is a thing I have never done for any one.”

“Well, do it for me, for I swear to you that I don’t love you as the others have loved you.”

“Well, keep it; but it only depends on me to make it useless to you, after all.”

“How?”

“There are bolts on the door.”

“Wretch!”

“I will have them taken off.”

“You love, then, a little?”

“I don’t know how it is, but it seems to me as if I do! Now, go; I can’t keep my eyes open.”

I held her in my arms for a few seconds and then went.

The streets were empty, the great city was still asleep, a sweet freshness circulated in the streets that a few hours later would be filled with the noise of men. It seemed to me as if this sleeping city belonged to me; I searched my memory for the names of those whose happiness I had once envied; and I could not recall one without finding myself the happier.

To be loved by a pure young girl, to be the first to reveal to her the strange mystery of love, is indeed a great happiness, but it is the simplest thing in the world. To take captive a heart which has had no experience of attack, is to enter an unfortified and ungarrisoned city. Education, family feeling, the sense of duty, the family, are strong sentinels, but there are no sentinels so vigilant as not to be deceived by a girl of sixteen to whom nature, by the voice of the man she loves, gives the first counsels of love, all the more ardent because they seem so pure.

The more a girl believes in goodness, the more easily will she give way, if not to her lover, at least to love, for being without mistrust she is without force, and to win her love is a triumph that can be gained by any young man of five-and-twenty. See how young girls are watched and guarded! The walls of convents are not high enough, mothers have no locks strong enough, religion has no duties constant enough, to shut these charming birds in their cages, cages not even strewn with flowers. Then how surely must they desire the world which is hidden from them, how surely must they find it tempting, how surely must they listen to the first voice which comes to tell its secrets through their bars, and bless the hand which is the first to raise a corner of the mysterious veil!

But to be really loved by a courtesan: that is a victory of infinitely greater difficulty. With them the body has worn out the soul, the senses have burned up the heart, dissipation has blunted the feelings. They have long known the words that we say to them, the means we use; they have sold the love that they inspire. They love by profession, and not by instinct. They are guarded better by their calculations than a virgin by her mother and her convent; and they have invented the word caprice for that unbartered love which they allow themselves from time to time, for a rest, for an excuse, for a consolation, like usurers, who cheat a thousand, and think they have bought their own redemption by once lending a sovereign to a poor devil who is dying of hunger without asking for interest or a receipt.

Then, when God allows love to a courtesan, that love, which at first seems like a pardon, becomes for her almost without penitence. When a creature who has all her past to reproach herself with is taken all at once by a profound, sincere, irresistible love, of which she had never felt herself capable; when she has confessed her love, how absolutely the man whom she loves dominates her! How strong he feels with his cruel right to say: You do no more for love than you have done for money. They know not what proof to give. A child, says the fable, having often amused himself by crying “Help! a wolf!” in order to disturb the labourers in the field, was one day devoured by a Wolf, because those whom he had so often deceived no longer believed in his cries for help. It is the same with these unhappy women when they love seriously. They have lied so often that no one will believe them, and in the midst of their remorse they are devoured by their love.

Hence those great devotions, those austere retreats from the world, of which some of them have given an example.

But when the man who inspires this redeeming love is great enough in soul to receive it without remembering the past, when he gives himself up to it, when, in short, he loves as he is loved, this man drains at one draught all earthly emotions, and after such a love his heart will be closed to every other.

I did not make these reflections on the morning when I returned home. They could but have been the presentiment of what was to happen to me, and, despite my love for Marguerite, I did not foresee such consequences. I make these reflections to-day. Now that all is irrevocably ended, they a rise naturally out of what has taken place.

But to return to the first day of my liaison. When I reached home I was in a state of mad gaiety. As I thought of how the barriers which my imagination had placed between Marguerite and myself had disappeared, of how she was now mine; of the place I now had in her thoughts, of the key to her room which I had in my pocket, and of my right to use this key, I was satisfied with life, proud of myself, and I loved God because he had let such things be.

One day a young man is passing in the street, he brushes against a woman, looks at her, turns, goes on his way. He does not know the woman, and she has pleasures, griefs, loves, in which he has no part. He does not exist for her, and perhaps, if he spoke to her, she would only laugh at him, as Marguerite had laughed at me. Weeks, months, years pass, and all at once, when they have each followed their fate along a different path, the logic of chance brings them face to face. The woman becomes the man’s mistress and loves him. How? why? Their two existences are henceforth one; they have scarcely begun to know one another when it seems as if they had known one another always, and all that had gone before is wiped out from the memory of the two lovers. It is curious, one must admit.

As for me, I no longer remembered how I had lived before that night. My whole being was exalted into joy at the memory of the words we had exchanged during that first night. Either Marguerite was very clever in deception, or she had conceived for me one of those sudden passions which are revealed in the first kiss, and which die, often enough, as suddenly as they were born.

The more I reflected the more I said to myself that Marguerite had no reason for feigning a love which she did not feel, and I said to myself also that women have two ways of loving, one of which may arise from the other: they love with the heart or with the senses. Often a woman takes a lover in obedience to the mere will of the senses, and learns without expecting it the mystery of immaterial love, and lives henceforth only through her heart; often a girl who has sought in marriage only the union of two pure affections receives the sudden revelation of physical love, that energetic conclusion of the purest impressions of the

Comments (0)