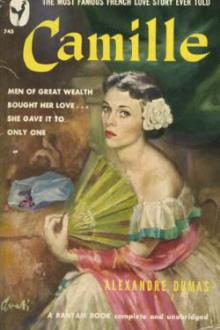

Camille - fils Alexandre Dumas (i have read the book a hundred times txt) 📗

- Author: fils Alexandre Dumas

- Performer: -

Book online «Camille - fils Alexandre Dumas (i have read the book a hundred times txt) 📗». Author fils Alexandre Dumas

I might have made Marguerite a present which would leave no doubt as to my generosity and permit me to feel properly quits of her, as of a kept woman, but I should have felt that I was offending by the least appearance of trafficking, if not the love which she had for me, at all events the love which I had for her, and since this love was so pure that it could admit no division, it could not pay by a present, however generous, the happiness that it had received, however short that happiness had been.

That is what I said to myself all night long, and what I was every moment prepared to go and say to Marguerite. When the day dawned I was still sleepless. I was in a fever. I could think of nothing but Marguerite.

As you can imagine, it was time to take a decided step, and finish either with the woman or with one’s scruples, if, that is, she would still be willing to see me. But you know well, one is always slow in taking a decided step; so, unable to remain within doors and not daring to call on Marguerite, I made one attempt in her direction, an attempt that I could always look upon as a mere chance if it succeeded.

It was nine o’clock, and I went at once to call upon Prudence, who asked to what she owed this early visit. I dared not tell her frankly what brought me. I replied that I had gone out early in order to reserve a place in the diligence for C., where my father lived.

“You are fortunate,” she said, “in being able to get away from Paris in this fine weather.”

I looked at Prudence, asking myself whether she was laughing at me, but her face was quite serious.

“Shall you go and say good-bye to Marguerite?” she continued, as seriously as before.

“No.”

“You are quite right.”

“You think so?”

“Naturally. Since you have broken with her, why should you see her again?”

“You know it is broken off?”

“She showed me your letter.”

“What did she say about it?”

“She said: ‘My dear Prudence, your protege is not polite; one thinks such letters, one does not write them.”’

“In what tone did she say that?”

“Laughingly, and she added: “He has had supper with me twice, and hasn’t even called.”’

That, then, was the effect produced by my letter and my jealousy. I was cruelly humiliated in the vanity of my affection.

“What did she do last night?”

“She went to the opera.”

“I know. And afterward?”

“She had supper at home.”

“Alone?”

“With the Comte de G., I believe.”

So my breaking with her had not changed one of her habits. It is for such reasons as this that certain people say to you: Don’t have anything more to do with the woman; she cares nothing about you.

“Well, I am very glad to find that Marguerite does not put herself out for me,” I said with a forced smile.

“She has very good reason not to. You have done what you were bound to do. You have been more reasonable than she, for she was really in love with you; she did nothing but talk of you. I don’t know what she would not have been capable of doing.”

“Why hasn’t she answered me, if she was in love with me?”

“Because she realizes she was mistaken in letting herself love you. Women sometimes allow you to be unfaithful to their love; they never allow you to wound their self-esteem; and one always wounds the self-esteem of a woman when, two days after one has become her lover, one leaves her, no matter for what reason. I know Marguerite; she would die sooner than reply.”

“What can I do, then?”

“Nothing. She will forget you, you will forget her, and neither will have any reproach to make against the other.”

“But if I write and ask her forgiveness?”

“Don’t do that, for she would forgive you.”

I could have flung my arms round Prudence’s neck.

A quarter of an hour later I was once more in my own quarters, and I wrote to Marguerite:

“Some one, who repents of a letter that he wrote yesterday and who will leave Paris tomorrow if you do not forgive him, wishes to know at what hour he might lay his repentance at your feet.

“When can he find you alone? for, you know, confessions must be made without witnesses.”

I folded this kind of madrigal in prose, and sent it by Joseph, who handed it to Marguerite herself; she replied that she would send the answer later.

I only went out to have a hasty dinner, and at eleven in the evening no reply had come. I made up my mind to endure it no longer, and to set out next day. In consequence of this resolution, and convinced that I should not sleep if I went to bed, I began to pack up my things.

It was hardly an hour after Joseph and I had begun preparing for my departure, when there was a violent ring at the door.

“Shall I go to the door?” said Joseph.

“Go,” I said, asking myself who it could be at such an hour, and not daring to believe that it was Marguerite.

“Sir,” said Joseph coming back to me, “it is two ladies.”

“It is we, Armand,” cried a voice that I recognised as that of Prudence.

I came out of my room. Prudence was standing looking around the place; Marguerite, seated on the sofa, was meditating. I went to her, knelt down, took her two hands, and, deeply moved, said to her, “Pardon.”

She kissed me on the forehead, and said:

“This is the third time that I have forgiven you.”

“I should have gone away tomorrow.”

“How can my visit change your plans? I have not come to hinder you from leaving Paris. I have come because I had no time to answer you during the day, and I did not wish to let you think that I was angry with you. Prudence didn’t want me to come; she said that I might be in the way.”

“You in the way, Marguerite! But how?”

“Well, you might have had a woman here,” said Prudence, “and it would hardly have been amusing for her to see two more arrive.”

During this remark Marguerite looked at me attentively.

“My dear Prudence,” I answered, “you do not know what you are saying.”

“What a nice place you’ve got!” Prudence went on. “May we see the bedroom?”

“Yes.”

Prudence went into the bedroom, not so much to see it as to make up for the foolish thing which she had just said, and to leave Marguerite and me alone.

“Why did you bring Prudence?” I asked her.

“Because she was at the theatre with me, and because when I leave here I want to have some one to see me home.”

“Could not I do?”

“Yes, but, besides not wishing to put you out, I was sure that if you came as far as my door you would want to come up, and as I could not let you, I did not wish to let you go away blaming me for saying ‘No.’”

“And why could you not let me come up?”

“Because I am watched, and the least suspicion might do me the greatest harm.”

“Is that really the only reason?”

“If there were any other, I would tell you; for we are not to have any secrets from one another now.”

“Come, Marguerite, I am not going to take a roundabout way of saying what I really want to say. Honestly, do you care for me a little?”

“A great deal.”

“Then why did you deceive me?”

“My friend, if I were the Duchess So and So, if I had two hundred thousand francs a year, and if I were your mistress and had another lover, you would have the right to ask me; but I am Mlle. Marguerite Gautier, I am forty thousand francs in debt, I have not a penny of my own, and I spend a hundred thousand francs a year. Your question becomes unnecessary and my answer useless.”

“You are right,” I said, letting my head sink on her knees; “but I love you madly.”

“Well, my friend, you must either love me a little less or understand me a little better. Your letter gave me a great deal of pain. If I had been free, first of all I would not have seen the count the day before yesterday, or, if I had, I should have come and asked your forgiveness as you ask me now, and in future I should have had no other lover but you. I fancied for a moment that I might give myself that happiness for six months; you would not have it; you insisted on knowing the means. Well, good heavens, the means were easy enough to guess! In employing them I was making a greater sacrifice for you than you imagine. I might have said to you, ‘I want twenty thousand francs’; you were in love with me and you would have found them, at the risk of reproaching me for it later on. I preferred to owe you nothing; you did not understand the scruple, for such it was. Those of us who are like me, when we have any heart at all, we give a meaning and a development to words and things unknown to other women; I repeat, then, that on the part of Marguerite Gautier the means which she used to pay her debts without asking you for the money necessary for it, was a scruple by which you ought to profit, without saying anything. If you had only met me to-day, you would be too delighted with what I promised you, and you would not question me as to what I did the day before yesterday. We are sometimes obliged to buy the satisfaction of our souls at the expense of our

Comments (0)