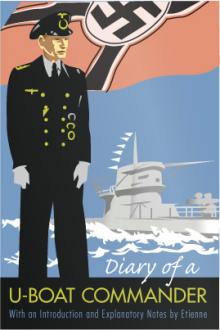

The Diary of a U-boat Commander - Sir King-Hall Stephen (best novels to read txt) 📗

- Author: Sir King-Hall Stephen

- Performer: 1846850495

Book online «The Diary of a U-boat Commander - Sir King-Hall Stephen (best novels to read txt) 📗». Author Sir King-Hall Stephen

All day I searched for my father and brother, but not a sign was to be seen, and at dusk I stood alone, faint and broken, amongst the ruins of my ancestors’ home. As I looked at this scene of desolation and I contrasted what had been my life twenty-four hours before and what it was then, something seemed to snap in my brain, and for the first time I cried. Oh! the blessed relief of those tears, my Karl, for I was a poor weak, helpless girl, and alone with death and bitterness all round me. Late that night I hid once more in my hay-loft and next morning I left Inkovano for ever. Before I left, I made a vow. It is because of this vow, my beloved, that I am to die. For I vowed by the body of our Saviour and the murdered bodies of my family that, whilst life was in me and the war was maintained, for so long would I work unceasingly for the Allies against Germany. As the war ran its fiery course, I have seen more and more that the Allies are the only ones who will do anything for Poland, my beloved country, so have I been strengthened in my vow.

I struck south on my feet, as a poor girl—I, the daughter of a princely family of Poland! No hardships were too great for me, provided I could reach Allied territory. I travelled from village to village as a singing girl, and once I was driven away with stones by villagers set upon me by a fanatical priest. I came by Cracow, and across the Carpathians, helped to pass the lines by a Hungarian Lieutenant—but I tricked him of his reward; I was not ready for that sacrifice. Then across the Hungarian plains to Buda-Pesth, where I remained three weeks, singing in a third-rate caf�, to make some money for my next stage. But I had to leave too soon—the old story!—this time it was the proprietor’s son. What beasts men are, my Karl! And yet to me you are above all other men, a prince amongst your fellows, and never did I love you so distractedly as that first night at the shooting-box, when I read the scorn in your eyes as you rejected me. I have no shame in telling you this. Am I not already in the grave? And then I must be silent and can only await your coming. After many struggles, wearisome to relate, I came to Hermanstadt, and there, whilst pushing my trade as a dancer, came into touch with a Hungarian band of smugglers, working across the mountain passes between Eastern Hungary and Roumania. I did certain work for these men, and in return crossed with them one bitter night in a thunderstorm into Roumania. At Bukharest I got a good engagement, and when I had saved a thousand marks, I bought a passport for five hundred, and came to Serbia, then staggering beneath the great Austrian offensive.

Once again I was in the horrors of a retreat, but I escaped, reaching Valona, and crossed to Brindisi, by the aid of a French officer to whom I told my story and who believed me. His name is Pierre Lemansour, and he lives at Bordeaux.

If fortune places him in your power, be kind to him, my Karl, for your Zoe’s sake.

I came to Rome; and thence to Paris. I stayed here three weeks, singing in a cabaret. Whilst here I tried to advance my plans in vain! What could I, a poor girl, do for the Allies? The Embassy laughed at me, all except one young attach� who tried to make love to me.

Then I thought of England—England, and her cold, hard islanders, phlegmatic in movements, slow to hate, slow to move, but once roused—ah! they never let go, these islanders!

One of their poets has said: “The mills of God grind slowly, but they grind exceeding small.”

That, my Karl, is like England.

They are your most terrible enemies, and you know it.

Do not be angry with me when you read this.

For me it is Poland, for you Germany.

Where I am going in a few hours there is no Poland, no Germany, no England, no war. And perhaps, perhaps, no love.

You and I, Karl, have loved, too well, perchance, but our love was above even the love of countries.

God made the love of men and women, then men and women created their countries.

I see the future before me, Karl, and I foresee that the struggle will be at the end of all things, between England and Germany. One will be in the dust.

Thus, I crossed to England and was swallowed up in the great city of London. England has always had a corner of her calculating heart for the small nations, and in London there is a Polish organization. I applied there, and one day I was taken to the Foreign Office, and found myself alone with a great Englishman. His name was—No, I promised, and it will not matter to you, for though he gave me my chance, I have no love for him, and he will never be in your power. Even as I write these words, he has probably taken a list from a locked safe and neatly ruled a red line through the name Zoe Sbeiliez. I tell you they know everything, these Englishmen. I told him my story, and then he asked me whether I was prepared to do all things for the Allies. I told him I was. He then said that I could go as agent for a back area in Belgium, and my centre would be Bruges. I agreed, and asked him innocently enough how I was to live in Bruges. He looked up from his desk and said:

“You will be given facilities to cross the Belgium-Holland frontier, as a German singer.”

“And then?” I asked.

“You will go to Bruges and make friends with an Army officer; he must be high up on the staff.”

I guessed what he meant, but hoped against hope, and I said: “How?”

I can still see his fish-like face, hair brushed back with scrupulous care, as without a shadow of emotion he looked up, puffed his pipe, and said in matter-of-fact tones:

“You have a pretty face and an excellent figure. Need I say more?”

I could have struck him in the face. I was speechless, my mind a whirl of conflicting emotions. I was roused by the level tones again.

“Is it too much—for Poland?”

Oh! the cunning of the man; he knew my weakness. Mechanically, I agreed. Certain details were settled, and he pressed a bell. Within five minutes I was walking back to my lodgings.

Thanks to a marvellous organization, which your police will never discover, my Karl, within three weeks I was singing on the Bruges music-hall stage, and accepted without question as being what I was not, a German artist from Dantzig. The men were soon round me, but I had no use for youngsters with money. I wanted a man with information. At last I found my man—the Colonel. He was on the Headquarters staff of the XIth Army, the army of occupation in Belgium, when I first met him. Subsequently he went back to regimental work; but by the time he was killed (and to realize what a release that meant for me, you would have had to have lived with him) I had established regular sources of information concerning which I will say no more. Let your country’s agents find them if they can. This must I say for the Colonel: he was a brute and a drunkard, but in his own gross way he loved me, and he licked my boots at my desire, but I had to pay the price. You are a man, and with all your loving sympathy you can but dimly realize what this costs a woman. To me it was a dual sacrifice of honour and life, but it was for Poland, and the memories of my parents and Alex steeled me and strengthened my resolution, and so, and so, my Karl, I paid the price.

My special work was on the military side, and consisted in making quarterly reports on the general dispositions of large bodies of troops, the massing of corps for spring offensives, and big pushes and hammer blows.

Then you came into my life! When the Colonel used to go away it was my habit to mix in the demi-mondaine society of Bruges, to try and live a few hours in which I could forget—oh! don’t think the worst! That sort of thing had no attraction for me. I didn’t seek oblivion in that direction! I had never even kissed anyone in Bruges until I kissed you that first night we met at dinner—I was attracted to you from the very first; the Colonel was due back in a few days, and I suddenly felt mad, and kissed you. I suppose you put me down as one of the usual kind, out to sell myself at a price varying between a good dinner and the rent of a flat! You will now know that I had already mortgaged my body to Poland.

Then a few days later you will remember we went down for that wonderful day in the forest, and for the first time, Karl, I began to see that I was really caring for you, and a faint realization of the dangers and impossibilities towards which we were drifting crossed my mind.

Do you remember how silent I was on the drive back? In a fashion, my Karl, I could foresee dimly a little of what was going to happen. I had a presentiment that the end would be disaster, but I thrust the idea away from me. Then came the day, just before one of your trips—oh! the agony, my darling, of those days, each an age in length, when you were at sea—when you told me at the flat that you loved me.

How I longed to throw my arms round your neck and abandon myself to your embraces, but I was still strong enough in those days to hold back for both our sakes.

Each time we were together I loved you more and more, and each time when you had gone I seemed to see with clearer vision the fatal and inevitable ending.

But I refused to give up the first real happiness that had been mine in my short and stormy life, and so I clung desperately to my idle dream.

I prayed, I prayed for hours, Karl, that the war might end, for I felt that in this lay our only hope—but what are one woman’s prayers, a sinful woman’s prayers, to the Creator of all things, and the war ground on in its endless agony just as it does tonight—Karl! Karl! will this torture ever end?

But I must hurry, there is still much to tell you, and Time goes on relentlessly just like the war; it is only life that ends. Then came the days I took you to the shooting-box for the first time,

Comments (0)