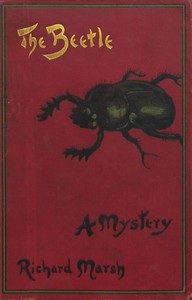

The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (books for 10th graders TXT) 📗

- Author: Richard Marsh

Book online «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (books for 10th graders TXT) 📗». Author Richard Marsh

‘Listen to me, papa. I will promise you never to speak to Paul Lessingham again, if you will promise me never to speak to Lord Cantilever again,—or to recognise him if you meet him in the street.’

‘You should have seen how papa glared. Lord Cantilever is the head of his party. Its august, and, I presume, reverenced leader. He is papa’s particular fetish. I am not sure that he does regard him as being any lower than the angels, but if he does it is certainly something in decimals. My suggestion seemed as outrageous to him as his suggestion seemed to me. But it is papa’s misfortune that he can only see one side of a question,—and that’s his own.’

‘You—you dare to compare Lord Cantilever to—to that—that—that—!’

‘I am not comparing them. I am not aware of there being anything in particular against Lord Cantilever,—that is against his character. But, of course, I should not dream of comparing a man of his calibre, with one of real ability, like Paul Lessingham. It would be to treat his lordship with too much severity.’

I could not help it,—but that did it. The rest of papa’s conversation was a jumble of explosions. It was all so sad.

Papa poured all the vials of his wrath upon Paul,—to his own sore disfigurement. He threatened me with all the pains and penalties of the inquisition if I did not immediately promise to hold no further communication with Mr Lessingham,—of course I did nothing of the kind. He cursed me, in default, by bell, book, and candle,—and by ever so many other things beside. He called me the most dreadful names,—me! his only child. He warned me that I should find myself in prison before I had done,—I am not sure that he did not hint darkly at the gallows. Finally, he drove me from the room in a whirlwind of anathemas.

CHAPTER XXVII.THE TERROR BY NIGHT

When I left papa,—or, rather, when papa had driven me from him—I went straight to the man whom I had found in the street. It was late, and I was feeling both tired and worried, so that I only thought of seeing for myself how he was. In some way, he seemed to be a link between Paul and myself, and as, at that moment, links of that kind were precious, I could not have gone to bed without learning something of his condition.

The nurse received me at the door.

‘Well, nurse, how’s the patient?’

Nurse was a plump, motherly woman, who had attended more than one odd protégé of mine, and whom I kept pretty constantly at my beck and call. She held out her hands.

‘It’s hard to tell. He hasn’t moved since I came.’

‘Not moved?—Is he still insensible?’

‘He seems to me to be in some sort of trance. He does not appear to breathe, and I can detect no pulsation, but the doctor says he’s still alive,—it’s the queerest case I ever saw.’

I went farther into the room. Directly I did so the man in the bed gave signs of life which were sufficiently unmistakable. Nurse hastened to him.

‘Why,’ she exclaimed, ‘he’s moving!—he might have heard you enter!’

He not only might have done, but it seemed possible that that was what he actually had done. As I approached the bed, he raised himself to a sitting posture, as, in the morning, he had done in the street, and he exclaimed, as if he addressed himself to someone whom he saw in front of him,—I cannot describe the almost more than human agony which was in his voice,

‘Paul Lessingham!—Beware!—The Beetle!’

What he meant I had not the slightest notion. Probably that was why what seemed more like a pronouncement of delirium than anything else had such an extraordinary effect upon my nerves. No sooner had he spoken than a sort of blank horror seemed to settle down upon my mind. I actually found myself trembling at the knees. I felt, all at once, as if I was standing in the immediate presence of something awful yet unseen.

As for the speaker, no sooner were the words out of his lips, than, as was the case in the morning, he relapsed into a condition of trance. Nurse, bending over him, announced the fact.

‘He’s gone off again!—What an extraordinary thing!—I suppose it is real.’ It was clear, from the tone of her voice, that she shared the doubt which had troubled the policeman. ‘There’s not a trace of a pulse. From the look of things he might be dead. Of one thing I’m sure, that there’s something unnatural about the man. No natural illness I ever heard of, takes hold of a man like this.’

Glancing up, she saw that there was something unusual in my face; an appearance which startled her.

‘Why, Miss Marjorie, what’s the matter!—You look quite ill!’

I felt ill, and worse than ill; but, at the same time, I was quite incapable of describing what I felt to nurse. For some inscrutable reason I had even lost the control of my tongue,—I stammered.

‘I—I—I’m not feeling very well, nurse; I—I—I think I’ll be better in bed.’

As I spoke, I staggered towards the door, conscious, all the while, that nurse was staring at me with eyes wide open. When I got out of the room, it seemed, in some incomprehensible fashion, as if something had left it with me, and that It and I were alone together in the corridor. So overcome was I by the consciousness of its immediate propinquity, that, all at once, I found myself cowering against the wall,—as if I expected something or someone to strike me.

How I reached my bedroom I do not know. I found Fanchette awaiting me. For the moment her presence was a positive comfort,—until I realised the amazement with which she was regarding me.

‘Mademoiselle is not well?’

‘Thank you, Fanchette, I—I am rather tired. I will undress myself to-night—you can go to bed.’

‘But if mademoiselle is so tired, will she not permit me to assist her?’

The suggestion was reasonable enough,—and kindly too; for, to say the least of it, she had as much cause for fatigue as I had. I hesitated. I should have liked to throw my arms about her neck, and beg her not to leave me; but, the plain truth is, I was ashamed. In my inner consciousness I was persuaded that the sense of terror which had suddenly come over me was so absolutely causeless, that I could not bear the notion of playing the craven in my maid’s eyes. While I hesitated, something seemed to sweep past me through the air, and to brush against my cheek in passing. I caught at Fanchette’s arm.

‘Fanchette!—Is there something with us in the room?’

‘Something with us in the room?—Mademoiselle?—What does mademoiselle mean?’

She looked disturbed,—which was, on the whole, excusable. Fanchette is not exactly a strong-minded person, and not likely to be much of a support when a support was most required. If I was going to play the fool, I would be my own audience. So I sent her off.

‘Did you not hear me tell you that I will undress myself?—you are to go to bed.’

She went to bed,—with quite sufficient willingness.

The instant that she was out of the room I wished that she was back again. Such a paroxysm of fear came over me, that I was incapable of stirring from the spot on which I stood, and it was all I could do to prevent myself from collapsing in heap on the floor. I had never, till then, had reason to suppose that I was a coward. Nor to suspect myself of being the possessor of ‘nerves.’ I was as little likely as anyone to be frightened by shadows. I told myself that the whole thing was sheer absurdity, and that I should be thoroughly ashamed of my own conduct when the morning came.

‘If you don’t want to be self-branded as a contemptible idiot, Marjorie Lindon, you will call up your courage, and these foolish fears will fly.’

But it would not do. Instead of flying, they grew worse. I became convinced,—and the process of conviction was terrible beyond words!—that there actually was something with me in the room, some invisible horror,—which, at any moment, might become visible. I seemed to understand—with a sense of agony which nothing can describe!—that this thing which was with me was with Paul. That we were linked together by the bond of a common, and a dreadful terror. That, at that moment, that same awful peril which was threatening me, was threatening him, and that I was powerless to move a finger in his aid. As with a sort of second sight, I saw out of the room in which I was, into another, in which Paul was crouching on the floor, covering his face with his hands, and shrieking. The vision came again and again with a degree of vividness of which I cannot give the least conception. At last the horror, and the reality of it, goaded me to frenzy.

‘Paul! Paul!’ I screamed.

As soon as I found my voice, the vision faded. Once more I understood that, as a matter of simple fact, I was standing in my own bedroom; that the lights were burning brightly; that I had not yet commenced to remove a particle of dress.

‘Am I going mad?’ I wondered.

I had heard of insanity taking extraordinary forms, but what could have caused softening of the brain in me I had not the faintest notion. Surely that sort of thing does not come on one—in such a wholly unmitigated form!—without the slightest notice,—and that my mental faculties were sound enough a few minutes back I was certain. The first premonition of anything of the kind had come upon me with the melodramatic utterance of the man I had found in the street.

‘Paul Lessingham!—Beware!—The Beetle!’

The words were ringing in my ears.—What was that?—There was a buzzing sound behind me. I turned to see what it was. It moved as I moved, so that it was still at my back. I swung, swiftly, right round on my heels. It still eluded me,—it was still behind.

I stood and listened,—what was it that hovered so persistently at my back?

The buzzing was distinctly audible. It was like the humming of a bee. Or—could it be a beetle?

My whole life long I have had an antipathy to beetles,—of any sort or kind. I have objected neither to rats nor mice, nor cows, nor bulls, nor snakes, nor spiders, nor toads, nor lizards, nor any of the thousand and one other creatures, animate or otherwise, to which so many people have a rooted, and, apparently, illogical dislike. My pet—and only—horror has been beetles. The mere suspicion of a harmless, and, I am told, necessary cockroach, being within several feet has always made me seriously uneasy. The thought that a great, winged beetle—to me, a flying beetle is the horror of horrors!—was with me in my bedroom,—goodness alone knew how it had got there!—was unendurable. Anyone who had beheld me during the next few moments would certainly have supposed I was deranged. I turned and twisted, sprang from side to side, screwed myself into impossible positions, in order to obtain a glimpse of the detested visitant,—but in vain. I could hear it all the time; but see it—never! The buzzing sound was continually behind.

The terror returned,—I began to think that my brain must be softening. I dashed to the bed. Flinging myself on my knees, I tried to pray. But I was speechless,—words would not come; my thoughts would not take shape. I all at once became conscious, as I struggled to ask help of God, that I was wrestling with something evil,—that if I only could ask help of Him, evil would flee. But I could not. I was helpless,—overmastered. I hid my face in the bedclothes, cramming my fingers into my ears. But the buzzing was behind me all the time.

I sprang up, striking out, blindly, wildly, right and left, hitting nothing,—the buzzing always came from a point at which, at the moment, I was not aiming.

I tore off my clothes. I had on a lovely frock which I had worn for the first time that night; I had had it specially made for the occasion of the Duchess’ ball, and—more especially—in honour of Paul’s great speech. I had said to myself, when I saw my image in a mirror, that it was the most exquisite gown I had ever had, that it suited me to perfection, and that it should continue in my wardrobe for many a day, if only as a souvenir of a memorable night. Now, in the madness of my terror, all reflections of that sort were forgotten. My

Comments (0)