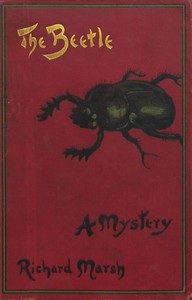

The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (books for 10th graders TXT) 📗

- Author: Richard Marsh

Book online «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (books for 10th graders TXT) 📗». Author Richard Marsh

Why he addressed Mr Holt in such a strain surpassed my comprehension. Mr Holt, however, evinced not the faintest symptoms of resentment,—he had become, on a sudden, more like an automaton than a man. Sydney continued to gaze at him as if he would have liked his glance to penetrate to his inmost soul.

‘Keep in front of me, if you please, Mr Holt, and lead the way to this mysterious apartment in which you claim to have had such a remarkable experience.’

Of me he asked in a whisper,

‘Did you bring a revolver?’

I was startled.

‘A revolver?—The idea!—How absurd you are!’

Sydney said something which was so rude—and so uncalled for!—that it was worthy of papa in his most violent moments.

‘I’d sooner be absurd than a fool in petticoats.’ I was so angry that I did not know what to say,—and before I could say it he went on. ‘Keep your eyes and ears well open; be surprised at nothing you see or hear. Stick close to me. And for goodness sake remain mistress of as many of your senses as you conveniently can.’

I had not the least idea what was the meaning of it all. To me there seemed nothing to make such a pother about. And yet I was conscious of a fluttering of the heart as if there soon might be something. I knew Sydney sufficiently well to be aware that he was one of the last men in the world to make a fuss without reason,—and that he was as little likely to suppose that there was a reason when as a matter of fact there was none.

Mr Holt led the way, as Sydney desired—or, rather, commanded, to the door of the room which was in front of the house. The door was closed. Sydney tapped on a panel. All was silence. He tapped again.

‘Anyone in there?’ he demanded.

As there was still no answer, he tried the handle. The door was locked.

‘The first sign of the presence of a human being we have had,—doors don’t lock themselves. It’s just possible that there may have been someone or something about the place, at some time or other, after all.’

Grasping the handle firmly, he shook it with all his might,—as he had done with the door at the back. So flimsily was the place constructed that he made even the walls to tremble.

‘Within there!—if anyone is in there!—if you don’t open this door, I shall.’

There was no response.

‘So be it!—I’m going to pursue my wild career of defiance of established law and order, and gain admission in one way, if I can’t in another.’

Putting his right shoulder against the door, he pushed with his whole force. Sydney is a big man, and very strong, and the door was weak. Shortly, the lock yielded before the continuous pressure, and the door flew open. Sydney whistled.

‘So!—It begins to occur to me, Mr Holt, that that story of yours may not have been such pure romance as it seemed.’

It was plain enough that, at any rate, this room had been occupied, and that recently,—and, if his taste in furniture could be taken as a test, by an eccentric occupant to boot. My own first impression was that there was someone, or something, living in it still,—an uncomfortable odour greeted our nostrils, which was suggestive of some evil-smelling animal. Sydney seemed to share my thought.

‘A pretty perfume, on my word! Let’s shed a little more light on the subject, and see what causes it. Marjorie, stop where you are until I tell you.’

I had noticed nothing, from without, peculiar about the appearance of the blind which screened the window, but it must have been made of some unusually thick material, for, within, the room was strangely dark. Sydney entered, with the intention of drawing up the blind, but he had scarcely taken a couple of steps when he stopped.

‘What’s that?’

‘It’s it,’ said Mr Holt, in a voice which was so unlike his own that it was scarcely recognisable.

‘It?—What do you mean by it?’

‘The Beetle!’

Judging from the sound of his voice Sydney was all at once in a state of odd excitement.

‘Oh, is it!—Then, if this time I don’t find out the how and the why and the wherefore of that charming conjuring trick, I’ll give you leave to write me down an ass,—with a great, big A.’

He rushed farther into the room,—apparently his efforts to lighten it did not meet with the immediate success which he desired.

‘What’s the matter with this confounded blind? There’s no cord! How do you pull it up?—What the—’

In the middle of his sentence Sydney ceased speaking. Suddenly Mr Holt, who was standing by my side on the threshold of the door, was seized with such a fit of trembling, that, fearing he was going to fall, I caught him by the arm. A most extraordinary look was on his face. His eyes were distended to their fullest width, as if with horror at what they saw in front of them. Great beads of perspiration were on his forehead.

‘It’s coming!’ he screamed.

Exactly what happened I do not know. But, as he spoke, I heard, proceeding from the room, the sound of the buzzing of wings. Instantly it recalled my experiences of the night before,—as it did so I was conscious of a most unpleasant qualm. Sydney swore a great oath, as if he were beside himself with rage.

‘If you won’t go up, you shall come down.’

I suppose, failing to find a cord, he seized the blind from below, and dragged it down,—it came, roller and all, clattering to the floor. The room was all in light. I hurried in. Sydney was standing by the window, with a look of perplexity upon his face which, under any other circumstances, would have been comical. He was holding papa’s revolver in his hand, and was glaring round and round the room, as if wholly at a loss to understand how it was he did not see what he was looking for.

‘Marjorie!’ he exclaimed. ‘Did you hear anything?’

‘Of course I did. It was that which I heard last night,—which so frightened me.’

‘Oh, was it? Then, by—’ in his excitement he must have been completely oblivious of my presence, for he used the most terrible language, ‘when I find it there’ll be a small discussion. It can’t have got out of the room,—I know the creature’s here; I not only heard it, I felt it brush against my face.—Holt, come inside and shut that door.’

Mr Holt raised his arms, as if he were exerting himself to make a forward movement,—but he remained rooted to the spot on which he stood.

‘I can’t!’ he cried.

‘You can’t!—Why?’

‘It won’t let me.’

‘What won’t let you?’

‘The Beetle!’

Sydney moved till he was close in front of him. He surveyed him with eager eyes. I was just at his back. I heard him murmur,—possibly to me.

‘By George!—It’s just as I thought!—The beggar’s hypnotised!’

Then he said aloud,

‘Can you see it now?’

‘Yes.’

‘Where?’

‘Behind you.’

As Mr Holt spoke, I again heard, quite close to me, that buzzing sound. Sydney seemed to hear it too,—it caused him to swing round so quickly that he all but whirled me off my feet.

‘I beg your pardon, Marjorie, but this is of the nature of an unparalleled experience,—didn’t you hear something then?’

‘I did,—distinctly; it was close to me,—within an inch or two of my face.’

We stared about us, then back at each other,—there was nothing else to be seen. Sydney laughed, doubtfully.

‘It’s uncommonly queer. I don’t want to suggest that there are visions about, or I might suspect myself of softening of the brain. But—it’s queer. There’s a trick about it somewhere, I am convinced; and no doubt it’s simple enough when you know how it’s done,—but the difficulty is to find that out.—Do you think our friend over there is acting?’

‘He looks to me as if he were ill.’

‘He does look ill. He also looks as if he were hypnotised. If he is, it must be by suggestion,—and that’s what makes me doubtful, because it will be the first plainly established case of hypnotism by suggestion I’ve encountered.—Holt!’

‘Yes.’

‘That,’ said Sydney in my ear, ‘is the voice and that is the manner of a hypnotised man, but, on the other hand, a person under influence generally responds only to the hypnotist,—which is another feature about our peculiar friend which arouses my suspicions.’ Then, aloud, ‘Don’t stand there like an idiot,—come inside.’

Again Mr Holt made an apparently futile effort to do as he was bid. It was painful to look at him,—he was like a feeble, frightened, tottering child, who would come on, but cannot.

‘I can’t.’

‘No nonsense, my man! Do you think that this is a performance in a booth, and that I am to be taken in by all the humbug of the professional mesmerist? Do as I tell you,—come into the room.’

There was a repetition, on Mr Holt’s part, of his previous pitiful struggle; this time it was longer sustained than before,—but the result was the same.

‘I can’t!’ he wailed.

‘Then I say you can,—and shall! If I pick you up, and carry you, perhaps you will not find yourself so helpless as you wish me to suppose.’

Sydney moved forward to put his threat into execution. As he did so, a strange alteration took place in Mr Holt’s demeanour.

CHAPTER XXX.THE SINGULAR BEHAVIOUR OF MR HOLT

I was standing in the middle of the room, Sydney was between the door and me; Mr Holt was in the hall, just outside the doorway, in which he, so to speak, was framed. As Sydney advanced towards him he was seized with a kind of convulsion,—he had to lean against the side of the door to save himself from falling. Sydney paused, and watched. The spasm went as suddenly as it came,—Mr Holt became as motionless as he had just now been the other way. He stood in an attitude of febrile expectancy,—his chin raised, his head thrown back, his eyes glancing upwards,—with the dreadful fixed glare which had come into them ever since we had entered the house. He looked to me as if his every faculty was strained in the act of listening,—not a muscle in his body seemed to move; he was as rigid as a figure carved in stone. Presently the rigidity gave place to what, to an onlooker, seemed causeless agitation.

‘I hear!’ he exclaimed, in the most curious voice I had ever heard. ‘I come!’

It was as though he was speaking to someone who was far away. Turning, he walked down the passage to the front door.

‘Hollo!’ cried Sydney. ‘Where are you off to?’

We both of us hastened to see. He was fumbling with the latch; before we could reach him, the door was open, and he was through it. Sydney, rushing after him, caught him on the step and held him by the arm.

‘What’s the meaning of this little caper?—Where do you think you’re going now?’

Mr Holt did not condescend to turn and look at him. He said, in the same dreamy, faraway, unnatural tone of voice,—and he kept his unwavering gaze fixed on what was apparently some distant object which was visible only to himself.

‘I am going to him. He calls me.’

‘Who calls you?’

‘The Lord of the Beetle.’

Whether Sydney released his arm or not I cannot say. As he spoke, he seemed to me to slip away from Sydney’s grasp. Passing through the gateway, turning to the right, he commenced to retrace his steps in the direction we had come. Sydney stared after him in unequivocal amazement. Then he looked at me.

‘Well!—this is a pretty fix!—now what’s to be done?’

‘What’s the matter with him?’ I inquired. ‘Is he mad?’

‘There’s method in his madness if he is. He’s in the same condition in which he was that night I saw him come out of the Apostle’s window.’ Sydney has a horrible habit of calling Paul ‘the Apostle’; I have spoken to him about it over and over again,—but my words have not made much impression. ‘He ought to be followed,—he may be sailing off to that mysterious friend of his this instant.—But, on the other hand, he mayn’t, and it may be nothing but a trick of our friend the conjurer’s to get us away from this elegant abode of his. He’s done me twice already, I don’t want to be done again,—and I distinctly do not want him to return and find me missing. He’s quite capable of taking the hint, and removing himself into

Comments (0)