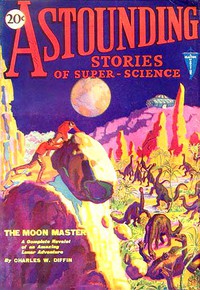

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (best books to read ever .txt) 📗

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (best books to read ever .txt) 📗». Author Various

Ortiz stopped short and said, in forced calmness:

"That also was the night that my father died."

Silence fell. Bell sat very still. The Teutonic figure spoke quietly after the clock had ticked for what seemed an interminable period.

"You didt know, then, that your father's death was arranged?"

Ortiz turned stiffly to look at him.

"Here," said the placid voice, quaintly sympathetic. "Look at these."

A hand extended a thick envelope. Ortiz took it, staring with wide, distended eyes. The round shouldered[Pg 126] figure stood up and seemed to shake itself. The stoop of its shoulders straightened out. One of the seemingly pudgy hands reached up and removed the thick spectacles. A bushy gray eyebrow peeled off. A straggly beard was removed. The other eyebrow.... Jamison nodded briefly to Bell, and turned to watch Ortiz.

And Ortiz was reading the contents of the envelope. His hands began to shake violently. He rested them on the desk-top so that he could continue to read. When he looked up his eyes were flaming.

"The real Herr Wiedkind," said Jamison dryly, "came up from Punta Arenas with special instructions from The Master. You have talents, Señor Ortiz, which The Master wished to use. Also you have considerable wealth and the prestige of an honorable family. But you were afflicted with ideas of honor and decency, which are disadvantageous in deputies of The Master. The real Herr Wiedkind had remarkable gifts in eradicating those ideas."

Jamison sat down and crossed his knees carefully.

"I looked you up because I knew The Master had killed your father," he added mildly, "and I thought you'd either be hunting The Master or he'd be hunting you. My name's Jamison. I killed the real Wiedkind and took his identification papers. He was a singularly unpleasant beast. His idea of pleasure made him seem a fatherly sort of person, very much like my make-up. He was constantly petting children, and appeared very benign. I am very, very glad that I killed him."

Ortiz tore at his collar, suddenly. He seemed to be choking.

"This—this says.... It is The Master's handwriting! I know it! And it says—"

"It says," Jamison observed calmly, "that since your father killed the previous deputy in an attempt to save you from The Master's poison, that you are to be prepared for the work your father had been assigned. Herr Wiedkind is given special orders about your—ah—moral education. In passing, I might say that your father was sent to the United States because it was known he'd killed the previous deputy. He told Bell he'd done that killing. And he was allowed to grow horribly nervous on his return. He was permitted to see the red spots, because he was officially—even as far as you were concerned—to commit suicide.

"It was intended that his nervousness was to be noticed. And a plane tried to deliver a message to him. Your father thought the parcel contained the antidote to the poison that was driving him mad. Actually, it was very conventional prussic acid. Your father would have drunk it and dropped dead, a suicide, after a conspicuous period of nervousness and worry."

Bell felt his cigarette burning his fingers. He had sat rigid until the thing burned short. He crushed out the coal, looking at Ortiz.

And Ortiz seemed to gasp for breath. But with an almost superhuman effort he calmed himself outwardly.

"I—think," he said with some difficulty, "that I should thank you. I do. But I do not think that you told me all of this without some motive. I abandon the service of The Master. But what is it that you wish me to do? You know, of course, that I can order both of you killed...."

Bell put down the stub of his cigarette very carefully.

"The only thing you can do," he said quietly, "is to die."

"True," said Ortiz with a ghastly smile. "But I would like my death to perform some service. The Master has no enemies save you two, and those of us who die on becoming his enemies. I would like, in dying, to do him some harm."

"I will promise," said Jamison grimly, "to see that The Master dies himself if you will have Bell and myself[Pg 127] put in a plane with fuel to Punta Arenas and a reasonable supply of weapons. I include the Señorita Canalejas as a matter of course."

Ortiz looked from one to the other. And suddenly he smiled once more. It was queer, that smile. It was not quite mirthless.

"You were right, just now," he observed calmly, "when as the Herr Wiedkind you said that I would quit the service of The Master when I ceased to despair. I begin to have hopes. You two men have done the impossible. You have fought The Master, you have learned many of his secrets, and you have corrupted a man to treason when treason means suicide. Perhaps, Señores, you will continue to achieve the impossible, and assassinate The Master."

He stood up, and though deathly pale continued to smile.

"I suggest, Señor, that you resume your complexion. And you, Señor Bell, you will be returned to your confinement. I will make the necessarily elaborate arrangements for my death."

Bell rose. He liked this young man. He said quietly:

"You said just now you wouldn't ask me to shake hands. May I ask you?..." He added almost apologetically as Ortiz's fingers closed upon his: "You see, when your father died I thought that I would be very glad if I felt that I would die as well. But I think"—he smiled wryly—"I think I'll have two examples to think of when my time comes."

In the morning a bulky, round shouldered figure entered the room in which Bell was confined.

"You will follow me," said a harsh voice.

Bell shrugged. He was marched down long passageways and many steps. He came out into the courtyard, where the glistening black car with the blank windows waited. At an imperious gesture, he got in and sat down with every appearance of composure, as of a man resignedly submitting to force he cannot resist. The thick spectacles of the Herr Wiedkind regarded him with a gogglelike effect. There was a long pause. Then the sound of footsteps. Paula appeared, deathly pale. She was ushered into the vehicle—and only Bell's swift gesture of a finger to his lips checked her cry of relief.

Voices outside. The guttural Spanish of the Herr Wiedkind. Other, emotionless voices replying. The Herr Wiedkind climbed heavily into the car and sat down, producing a huge revolver which bore steadily upon Bell. The door closed, and he made a swift gesture of caution.

"Idt may be," said the Germanic voice harshly, "that you and the young ladty haff much to say to each other. But idt can wait. And I warn you, mein Herr, that at the first movement I shall fire."

Bell relaxed. There was the purring of the motor. The car moved off. Obviously there was some microphonic attachment inside the tonneau which carried every word within the locked vehicle to the ears of the two men upon the chauffeur's seat. An excellent idea for protection against treachery. Bell smiled, and moved so that his lips were a bare half-inch from Paula's ears.

"Try to weep, loudly," he said in the faintest of whispers. "This man is a friend."

But Paula could only stare at the bulky figure sitting opposite until he suddenly removed the spectacles, and smiled dryly, and then reached in his pockets and handed Bell two automatic pistols, and extended a tiny but very wicked weapon to Paula. He motioned to her to conceal it.

Jamison—moving to make the minimum of noise—handed Bell a sheet of stiff cardboard. It passed into Bell's[Pg 128] fingers without a rustle. He showed it silently to Paula.

We were overheard last night by someone. We don't know who or how much he heard. Dictaphone in the room we talked in. Can't find out who it was or what action he's taken. We may be riding into a trap now. Ortiz has disappeared. He may be dead. We can only wait and see.

The car was moving as if in city traffic, a swift dash forward and a sudden stop, and then another swift dash. But the walls within were padded so that no sound came from without save the faint vibration of the motor and now and then the distinct flexing of a spring. Then the car turned a corner. It went more rapidly. It turned another corner. And another....

In the light of the bright dome light, Bell saw beads of sweat coming out on Jamison's face. He did not dare to speak, but he formed words with his lips.

"He's turning wrong! This isn't the way to the field!"

Bell's jaws clenched. He took out his two automatics and looked at them carefully. And then, much too short a time from the departure for the flying field to have been reached, the car checked. It went over rough cobblestones, and Bell himself knew well that there had been no cobbled roadway between the flying field and his prison. And then the car went up a sort of ramp, a fairly steep incline which by the feel of the motor was taken in low, and on for a short distance more. Then the car stopped and the motor was cut off.

Keys rattled in the lock outside. The door opened. The blunt barrel of an automatic pistol peered in.

(To be concluded in the next issue.)

The Readers' Corner A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding StoriesAbout Reprints

From time to time the Editors of Astounding Stories receive letters, like the two that follow, in which Readers beg us to run reprints, and now we feel it is time to call attention to the very good reasons why we must refuse.

We admit, right off, that some splendid Science Fiction stories have been published in the past—but are those now being printed in any way inferior to them? Aren't even better ones being written to-day?—since a whole civilization now stirs with active interest in science?—since three or five times as many writers are now supplying us with stories to choose from?—since science and scientific theory have reached so immeasurably much farther into the Realm of the Unknown Possible?

The answer is an emphatic Yes. We all know it.

"A Trip to the Moon"—for instance—was a good story, but shall we keep reprinting it to-day, when recent revolutionary theories of space-time scream to modern authors for Science-Fiction treatment? In the last ten years the whole aspect, the whole future of science has broadened; we have sensed an infinity beyond infinity; and who would be so un-modern as to cling to the oft-told stories of the older science and neglect the thrilling reaches of the new!

The Saturday Evening Post—again, for instance—has been publishing good stories for years, but who would have them reprint the old ones instead of keep giving us good new ones?

Would it be fair to 99% of our Readers to force on them reprint novels they have already read, or had a chance to read, to favor the 1% who have missed them? Of course it wouldn't, and all[Pg 129] of our Readers in that 1% will gladly admit it.

And how about our authors? Contrary to the old-fashioned opinion, authors must eat—and how will they eat, and lead respectable lives, and keep out of jail, if we keep reprinting their old stories and turning down their new ones? After all, eating is very important; those who wouldn't simply refrain from eating would have to get jobs as messengers, and errand boys, etc.—with the result that much of our fascinating modern Science Fiction would never be written!

It would be much cheaper for us to buy once-used material. It would greatly reduce our task of carefully reading every story that comes to our office, in hopes to finding a fine, new story, or a potentially good author. But it would be very unwise, and very unfair, as you have seen.

Many more reasons could be given, but these few are the more important ones back of our policy of avoiding reprints. Enough said!—The Editor.

Wants Reprints

Dear Editor:

In you April issue, in answer to a correspondent, you stated that you were avoiding reprints. Now, that's too bad. Some of the best Science-Fiction tales are reprints. Witness:

"The Blind Spot," by Homer Eon Flint and Austin Hall; "The War In The Air," by H. G. Wells; "The

Comments (0)