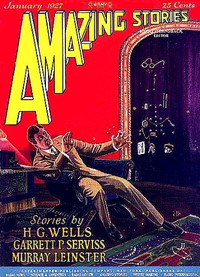

The Red Dust by Murray Leinster (recommended reading TXT) 📗

- Author: Murray Leinster

Book online «The Red Dust by Murray Leinster (recommended reading TXT) 📗». Author Murray Leinster

Behind him the nearly naked people followed reluctantly. Here a woman with a baby in her arms, there children of nine or ten, unable to resist the Instinct to play even in the presence of the manifold dangers of the march. They ate hungrily of the lumps of mushroom they had been ordered to carry. Then a long-legged boy, his eyes roving anxiously about in search of danger followed.

Thirty thousand years of flight from every peril had deeply submerged the combative nature of humanity. After the boy came two men, one with a short spear, and the other with a club, each with a huge mass of edible mushroom under his free arm, and both badly frightened at the idea of fleeing from dangers they knew and feared to dangers they did not know and consequently feared much more.

So was the caravan spread out. It made its way across the country with many deviations from a fixed line, and with many halts and pauses. Once a shrill stridulation filled all the air before them, a monster sound compounded of innumerable clickings and high-pitched cries.

They came to the tip of an eminence and saw a great space of ground covered with tiny black bodies locked in combat. For quite half a mile in either direction the earth was black with ants, snapping and biting at each other, locked in vise-like embraces, each combatant couple trampled under the feet of the contending armies, with no thought of surrender or quarter.

The sound of the clashing of fierce jaws upon horny armor, the cries of the maimed, and strange sounds made by the dying, and above all, the whining battle-cry of each of the fighting hordes, made a sustained uproar that was almost deafening.

From either side of the battle-ground a pathway led back to separate ant-cities, a pathway marked by the hurrying groups of reinforcements rushing to the fight. Tiny as the ants were, for once no lumbering beetle swaggered insolently in their path, nor did the hunting-spiders mark them out for prey. Only little creatures smaller than the combatants themselves made use of the insect war for purposes of their own.

These were little gray ants barely more than four inches long, who scurried about in and among the fighting creatures with marvelous dexterity, carrying off, piece-meal, the bodies of the dead, and slaying the wounded for the same fate.

They hung about the edges of the battle, and invaded the abandoned areas when the tide of battle shifted, insect guerrillas, fighting for their own hands, careless of the origin of the quarrel, espousing no cause, simply salvaging the dead and living d�bris of the combat.

Burl and his little group of followers had to make a wide detour to avoid the battle itself, and the passage between bodies of reinforcements hurrying to the scene of strife was a matter of some difficulty. The ants running rapidly toward the battle-field were hugely excited. Their antenn� waved wildly, and the infrequent wounded one, limping back toward the city, was instantly and repeatedly challenged by the advancing insects.

They crossed their antenn� upon his, and required thorough evidence that he was of the proper city before allowing him to proceed. Once they arrived at the battle-field they flung themselves into the fray, becoming lost and indistinguishable in the tide of straining, fighting black bodies.

Men in such a battle, without distinguishing marks or battle-cries, would have fought among themselves as often as against their foes, but the ants had a much simpler method of identification. Each ant-city possesses its individual odor—a variant on the scent of formic acid—and each individual of that city is recognized in his world quite simply and surely by the way he smells.

The little tribe of human beings passed precariously behind a group of a hundred excited insect warriors, and before the following group of forty equally excited black insects. Burl hurried on with his following, putting many miles of perilous territory behind before nightfall. Many times during the day they saw the sudden billowing of a red-brown dust-cloud from the earth, and more than once they came upon the empty skin and drooping stalk of one of the red mushrooms, and more often still they came upon the mushrooms themselves, grown fat and taut, prepared to send their deadly spores into the air when the pressure from within became more than the leathery skin could stand.

That night the tribe hid among the bases of giant puff-balls, which at a touch shot out a puff of white powder resembling smoke. The powder was precisely the same in nature as that cast out by the red mushrooms, but its effects were marvelously—and mercifully—different; it was innocuous.

Burl slept soundly this night, having been two days and a night without rest, but the remainder of his tribe, and even Saya, were fearful and afraid, listening ceaselessly all through the dark hours for the menacing sounds of creatures coming to prey upon them.

And so for a week the march kept on. Burl would not allow his tribe to stop to forage for food. The red mushrooms were all about. Once one of the little children was caught in a whirling eddy of red dust, and its mother rushed into the deadly stuff to seize it and bring it out. Then the tribe had to hide for three days while the two of them recovered from the debilitating poison.

Once, too, they found a half-acre patch of the giant cabbages—there were six of them full grown, and a dozen or more smaller ones—and Burl took two men and speared two of the huge, twelve-foot slugs that fed upon the leaves. When the tribe passed on it was gorged on the fat meat of the slugs, and there was much soft fur, so that all the tribefolk wore loin-cloths of the yellow stuff.

There were perils, too, in the journey. On the fourth day of the tribe's traveling, Burl froze suddenly into stillness. One of the hairy tarantulas—a trap-door spider with a black belly—had fallen upon a scarab�us beetle, and was devouring it only a hundred yards ahead.

The tribefolk, trembling, went back for half a mile or more in panic-stricken silence, and refused to advance until he had led them a detour of two or three miles to one side of the dangerous spot.

Long, fear-ridden marches through perilous countries unknown to them, through the golden aisles of yellow mushroom forests, over the flaking surfaces of plains covered with many-colored "rusts" and molds; pauses beside turbid pools whose waters were concealed by thick layers of green slime, and other evil-smelling ponds which foamed and bubbled slowly, which were covered with pasty yeasts that rose in strange forms of discolored foam.

Fleeting glimpses they had of the glistening spokes of symmetrical spiders'-webs, whose least thread it would have been beyond the power of the strongest of the tribe to break. They passed through a forest of puff-balls, which boomed when touched and shot a puff of vapor from their open mouths.

Once they saw a long and sinuous insect that fled before them and disappeared into a burrow in the ground, running with incredible speed upon legs of uncountable number. It was a centipede all of thirty feet in length, and when they crossed the path it had followed a horrible stench came to their nostrils so that they hurried on.

Long escape from unguessed dangers brought boldness, of a sort, to the pink-skinned men, and they would have rested. They went to Burl with their complaint, and he simply pointed with his hands behind them. There were three little clouds of brownish vapor in the air, where they could see, along the road they had traversed. To the right of them a dust-cloud was just settling, and to the left another rose as they looked.

A new trick of the deadly dust became apparent now. Toward the end of a day in which they had traveled a long distance, one of the little children ran a little to the left of the route its elders were following. The earth had taken on a brownish hue, and the child stirred up the surface mould with its feet.

The brownish dust that had settled there was raised again, and the child ran, crying and choking, to its mother, its lungs burning as with fire, and its eyes like hot coals. Another day would pass before the child could walk.

In a strange country, knowing nothing of the dangers that might assail the tribe while waiting for the child to recover, Burl looked about for a hiding-place. Far over to the right a low cliff, perhaps twenty or thirty feet high, showed sides of crumbling, yellow clay, and from where Burl stood he could see the dark openings of burrows scattered here and there upon its face.

He watched for a time, to see if any bee or wasp inhabited them, knowing that many kinds of both insects dig burrows for their young, and do not occupy them themselves. No dark forms appeared, however, and he led his people toward the openings.

The appearance of the holes confirmed his surmise. They had been dug months before by mining bees, and the entrances were "weathered" and worn. The tribefolk made their way into the three-foot tunnels, and hid themselves, seizing the opportunity to gorge themselves upon the food they carried.

Burl stationed himself near the outer end of one of the little caves to watch for signs of danger. While waiting he poked curiously with his spear at a little pile of white and sticky parchment-like stuff he saw just within the mouth of the tunnel.

Instantly movement became visible. Fifty, sixty, or a hundred tiny creatures, no more than half an inch in length, tumbled pell-mell from the dirty-white heap. Awkward legs, tiny, greenish-black bodies, and bristles protruding in every direction made them strange to look upon.

They had tumbled from the whitish heap and now they made haste to hide themselves in it again, moving slowly and clumsily, with immense effort and laborious contortions of their bodies.

Burl had never seen any insect progress in such a slow and ineffective fashion before. He drew one little insect back with the point of his spear and examined it from a safe distance. Tiny jaws before the head met like twin sickles, and the whole body was shaped like a rounded diamond lozenge.

Burl knew that no insect of such small size could be dangerous, and leaned over, then took one creature in his hand. It wriggled frantically and slipped from his fingers, dropping upon the soft yellow caterpillar-fur he had about his middle. Instantly, as if it were a conjuring trick, the little insect vanished, and Burl searched for a matter of minutes before he found it hidden deep in the long, soft hairs of the fur, resting motionless, and evidently at ease.

It was a bee-louse, the first larval form of a beetle whose horny armor could be seen in fragments for yards before the clayey cliff-side. Hidden in the openings of the bee's tunnel, it waited until the bee-grubs farther back in their separate cells should complete their changes of form and emerge into the open air, passing over the cluster of tiny creatures at the doorway. As the bees pass, the little bee-lice would clamber in eager haste up their hairy legs and come to rest in the fur about their thoraxes. Then, weeks later, when the bees in turn made other cells and stocked them with honey for the eggs they would lay, the tiny creatures would slip from their resting-places and be left behind in the fully provisioned cell, to eat not only the honey the bee had so laboriously acquired, but the very grub hatched from the bee's egg.

Burl had no difficulty in detaching the small insect and casting it away, but in doing so discovered three more that had hidden themselves in his furry garment, no doubt thinking it the coat of their natural, though unwilling hosts. He plucked them away, and discovered more, and more. His garment was the hiding-place for dozens of the creatures.

Disgusted and annoyed, he went out of the cavern and to a spot some distance away, where he took off his robe and pounded it with the flat side of his spear to dislodge the visitors. They dropped out one by one, reluctantly, and finally the garment was clean of them. Then Burl heard a shout from the direction of the mining-bee caves, and hastened toward the sound.

It was then drawing toward the time of darkness, but one of the tribesmen had ventured out and found no less than three of the great imperial mushrooms. Of the three, one had been attacked by a parasitic purple mould,

Comments (0)