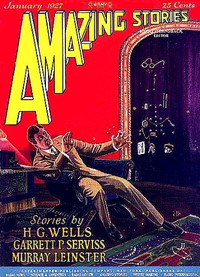

The Red Dust by Murray Leinster (recommended reading TXT) 📗

- Author: Murray Leinster

Book online «The Red Dust by Murray Leinster (recommended reading TXT) 📗». Author Murray Leinster

Burl wrestled with his problem for an hour, and then gave up in disgust. He set off at random, with the leg of the huge insect flung over his shoulder and the long antenn� clasped in his hand with his spear. He turned to look at his victim of the night before just before plunging into the near-by mushroom forest, and saw that it was already the center of a mass of tiny black bodies, pulling and hacking at the tough armor, and carving out great lumps of the succulent flesh to be carried to the near-by ant city.

In the teeming life of the insect world death is an opportunity for the survivors. There is a strangely tense and fearful competition for the bodies of the slain. There had been barely an hour of daylight in which the ants might seek for provender, yet in that little time the freshly killed beetle had been found and was being skilfully and carefully exploited. When the body of one of the larger insects fell to the ground, there was a mighty rush, a fierce race, among all the tribes of scavengers to see who should be first.

Usually the ants had come upon the scene and were inquisitively exploring the carcass long before even the flesh-flies had arrived, who dropped their living maggots upon the creature. The blue-bottles came still later, to daub their masses of white eggs about the delicate membranes of the eye.

And while all the preceding scavengers were at work, furtive beetles and tiny insects burrowed below the reeking body to attack the highly scented flesh from a fresh angle.

Each working independently of the others, they commonly appeared in the order of the delicacy of the sense which could lead them to a source of food, though accident could and sometimes did afford one group of workers in putrescence an advantage over the others.

Thus, sometimes a blue-bottle anticipated even the eager ants, and again the very flesh-flies dropped their squirming offspring upon a limp form that was already being undermined by white-bellied things working in the darkness below the body.

Burl grimaced at the busy ants and buzzing flies, and disappeared into the mushroom forest. Here for a long time he moved cautiously and silently through the aisles of tangled stalks and the spongy, round heads of the fungoids. Now and then he saw one of the red toadstools, and made a wide detour around it. Twice they burst within his sight, circumscribed as his vision was by the toadstools among which he was traveling.

Each time he ran hastily to put as much distance as possible between himself and the deadly red dust. He traveled for an hour or more, looking constantly for familiar landmarks that might guide him to his tribe. He knew that if he came upon any place he had seen while with his tribe he could follow the path they had traveled and in time rejoin them.

For many hours he went on, alert for signs of danger. He was quite ignorant of the fact that there were such things as points of the compass, and though he had a distinct notion that he was not moving in a straight line, he did not realize that he was actually moving in a colossal half-circle. After walking steadily for nearly four hours he was no more than three miles in a direct line from his starting-point. As it happened, his uncertainty of direction was fortunate.

The night before the tribe had been feeding happily upon one of the immense edible mushrooms, when they heard Burl's abruptly changing cry. It had begun as a shout of triumph, and ended as a scream of fear. Then they heard hurried wing-beats as a creature rose into the air in a scurry of desperation. The throbbing of huge wings ended in a heavy fall, followed by another flight.

Velvety darkness masked the sky, and the tribesmen could only stare off into the blackness, where their leader had vanished, and begin to tremble, wondering what they should do in a strange country with no bold chief to guide them.

He was the first man to whom the tribe had ever offered allegiance, but their submission had been all the more complete for that fact, and his loss was the more appalling.

Burl had mistaken their lack of timidity. He had thought it independence, and indifference to him. As a matter of fact, it was security because the tribe felt safe under his tutelage. Now that he had vanished, and in a fashion that seemed to mean his death, their old fears returned to them reenforced by the strangeness of their surroundings.

They huddled together and whispered their fright to one another, listening the while in panic-stricken apprehension for signs of danger. The tribesmen visualized Burl caught in fiercely toothed limbs, being rent and torn in mid air by horny, insatiable jaws, his blood falling in great spurts toward the earth below. They caught a faint, reedy cry, and shuddered, pressing closer together.

And so through the long night they waited in trembling silence. Had a hunting spider appeared among them they would not have lifted a hand to defend themselves, but would have fled despairingly, would probably have scattered and lost touch with one another, and spent the remainder of their lives as solitary fugitives, snatching fear-ridden rest in strange hiding-places.

But day came again, and they looked into each other's eyes, reading in each the selfsame panic and fear. Saya was probably the most pitiful of all the group. Burl was to have been her mate, and her face was white and drawn beyond that of any of the rest of the tribefolk.

With the day, they did not move, but remained clustered about the huge mushroom on which they had been feeding the night before. They spoke in hushed and fearful tones, huddled together, searching all the horizon for insect enemies. Saya would not eat, but sat still, staring before her in unseeing indifference. Burl was dead.

A hundred yards from where they crouched a red mushroom glistened in the pale light of the new day. Its tough skin was taut and bulging, resisting the pressure of the spores within. But slowly, as the morning wore on, some of the moisture that had kept the skin soft and flaccid during the night evaporated.

The skin had a strong tendency to contract, like green leather when drying. The spores within it strove to expand. The opposing forces produced a tension that grew greater and greater as more and more of the moisture was absorbed by the air. At last the skin could hold no longer.

With a ripping sound that could be heard for hundreds of feet, the tough wrapping split and tore across its top, and with a hollow, booming noise the compressed mass of deadly spores rushed into the air, making a pyramidal cloud of brown-red dust some sixty feet in height.

The tribesmen quivered at the noise and faced the dust cloud for a fleeting instant, then ran pell-mell to escape the slowly moving tide of death as the almost imperceptible breeze wafted it slowly toward them. Men and women, boys and girls, they fled in a mad rush from the deadly stuff, not pausing to see that even as it advanced it settled slowly to the ground, nor stopping to observe its path that they might step aside and let it go safely by.

Saya fled with the rest, but without their extreme panic. She fled because the others had done so, and ran more carelessly, struggling with a half-formed idea that it did not particularly matter whether she were caught or not.

She fell slightly behind the others, without being noticed. Then quite abruptly a stone turned under her foot, and she fell headlong, striking her head violently against a second stone. Then she lay quite still while the red cloud billowed slowly toward her, drifting gently in the faint, hardly perceptible breeze.

It drew nearer and nearer, settling slowly, but still a huge and menacing mass of deadly dust. It gradually flattened out, too, so that though it had been a rounded cone at first, it flowed over the minor inequalities of the ground as a huge and tenuous leech might have crawled, sucking from all breathing creatures the life they had within them.

A hundred and fifty yards away, a hundred yards away, then only fifty yards away. From where Saya lay unconscious on the earth, eddies within the moving mass could be seen, and the edges took on a striated appearance, telling of the curling of the dust wreaths in the larger mass of deadly powder.

The deliberate advance kept on, seeming almost purposeful. It would have seemed possible to draw from the unhurried, menacing movement of the poisonous stuff that some malign intelligence was concealed in it, that it was, in fact, a living creature. But when the misty edges of the cloud were no more than twenty-five yards from Saya's prostrate body a breeze from one side sprang up—a vagrant, fitful little breeze, that first halted the red cloud and threw it into confusion and then drove it to one side, so that it passed Saya without harming her, though a single trailing wisp of dark-red mist floated very close to her.

Then for a time Saya lay still indeed, only her breast rising and falling gently with faint and irregular breaths. Her head had struck a sharp-edged stone in her fall, and a tiny pool of sticky red had gathered from the wound.

Perhaps thirty feet from where she lay, three small toadstools grew in a little clump, their bases so close together that they seemed but one. From between two of them, however, just where they parted, twin tufts of reddish threads appeared, twinkling back and forth, and in and out. As if they had given some reassuring sign, two slender antenn� followed, then bulging eyes, and then a small black body which had bright-red scalloped markings upon the wing-cases.

It was a tiny beetle no more than eight inches long—a burying-beetle. It drew near Saya's body and clambered upon her, explored the ground by her side, moving all the time in feverish haste, and at last dived into the ground beneath her shoulder, casting back a little shower of hastily dug earth as it disappeared.

Ten minutes later another similar insect appeared, and upon the heels of the second a third. Each of them made the same hasty examination, and each dived under the still form. Presently the earth seemed to billow at a spot along Saya's side, then at another. Perhaps ten minutes after the arrival of the third beetle a little rampart had reared itself all about Saya's body, precisely following the outline of her form. Then her body moved slightly, in a number of tiny jerks, and seemed to settle perhaps half an inch into the ground.

The burying beetles were of those who exploited the bodies of the fallen. Working from below, they excavated the earth from the under side of such prizes as they came upon, then turned upon their backs and thrust with their legs, jerking the body so it sank into the shallow excavation they had prepared.

The process would be repeated until at last the whole of the gift of fortune had sunk below the surrounding surface and the loosened earth fell in upon the top, thus completing the inhumation.

Then in the darkness the beetles would feast and rear their young, gorging upon the plentiful supply of succulent foodstuff they had hidden from jealous fellow scavengers above them.

But Saya was alive. Thirty thousand years before, when scientists examined into the habits of the burying-beetles, or the sexton-beetles, they had declared that fresh meat or living meat would not be touched. They based their statement solely upon the fact that the insects (then tiny creatures indeed) did not appear until the trap-meat placed by the investigators had remained untouched for days.

Conditions had changed in thirty thousand years. The ever-present ants and the sharp-eyed flies were keen rivals of the brightly arrayed beetles. Usually the tribes of creatures who worked in the darkness below ground came after the ants had taken their toll, and the flies sipped daintily.

When Saya fell unconscious upon the ground, however, it was the one accident that caused the burying-beetle to find her first, before the ants had come to tear the flesh from her slender, soft-skinned body. She breathed gently and irregularly, her face drawn with the sorrow of the night before, while desperately hurrying beetles swarmed beneath her body, channeling away the earth so that she would sink lower and lower into the ground.

An inch, and a long wait. Then she sank slowly a second inch. The bright-red tufts of thread appeared again, and a beetle made his way to the open air. He moved hastily about, inspecting the progress of the work. He dived below again. Another inch, and after a long time another inch was excavated.

Burl stepped out

Comments (0)