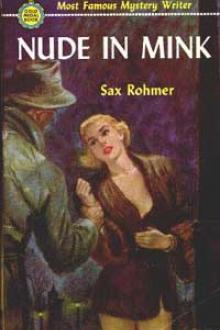

Nude in Mink - Sax Rohmer (fun books to read for adults txt) 📗

- Author: Sax Rohmer

- Performer: -

Book online «Nude in Mink - Sax Rohmer (fun books to read for adults txt) 📗». Author Sax Rohmer

Nude in Mink

by

Sax Rohmer

New York: Fawcett - Gold Medal Original

1950

“DON’T turn. Don’t stop. This is Maitland behind you. Just go right ahead. Tell me where you live and stand by to let me in the moment I get there.”

Mark Donovan didn’t turn, and he didn’t stop; he went straight on through the darkness of a foggy night. He had recognised that tense voice. The speaker was Dr. Steel Maitland right enough—whom he had last seen in Cairo! But his heart began to beat a shade faster when he spoke: Maitland was no more than a pace to the rear.

“One-twenty-three Bruton Street. First floor. Walk straight up.”

“Expect me any time, Donovan. Don’t fail.”

He had an impression that Maitland had fallen back but Donovan pressed on. His brain became a whirligig. The vapoury masses about him which were Bond Street whispered menaces. What, in reason’s name, had happened to Maitland? Why must he not stop, but go right ahead?

There was little traffic when, crossing, he continued on his way. The blanket-like hush of foggy London had become in a moment a mysterious hush, an ominous hush: it bore down upon him. That rara avis (in fog) a taxi, passed every now and again; pedestrians materialised out of yellow shadow, phantoms preceded by the glow of a cigarette, and merged into shadow again.

He grew conscious of distrust. Amongst these ships that passed in the night some might be enemies.

Bruton Street, former abode of fashion, sounded empty right to Berkeley Square. Donovan’s footsteps hollowly disturbed a ghostly silence where, once, dance bands had played, sleekly gowned women come and gone under striped awnings; where, in times yet earlier, bucks of the Regency had supped, and gambled, and fought.

From here the present Queen had been borne away in a Cinderella coach to her wedding in Westminster Abbey: here, streams of traffic had congested the fairway when society entertained; here, long ago, linkboys had steered the drunken reveller home.

Where were the fairy coach, the cars, the linkboys?

Lost, to live again only in the pages of history. This was the London which the Nazis had made; and Steel Maitland had said, “Go right ahead. Stand by to let me in the moment I get there.”

As Donovan pushed the door open he stood for a moment listening, before allowing it to swing to again. The hush of Bruton Street was broken by a solitary tread. He waited. The measured steps drew nearer. A light was flashed upon him.

“Good night, sir.”

“Good night, Constable.”

He closed the door and went upstairs. On the landing he paused, listening again.

There was no sound.

Once inside his own apartment, the lobby lights up, he heaved a sigh of relief. A moment later he was laughing at himself. Undoubtedly, he needed a rest. Not since he had landed with an American task force at a selected point, to find enemy guns raining bullets on the spot, had he been so frightened: his heart was still beating ridiculously!

Those modest belongings which Donovan had distributed around the apartment struck a note of reassuring familiarity. For the rest, its appointments were strictly utilitarian. The owner, from whom he leased it, had removed all but essentials. A whisky and soda restored him, and he sat down to consider the question: What was it all about?

Lighting a cigarette, Donovan turned this problem over in his mind, and realising the urgency in Maitland’s voice, came to the conclusion that some mysterious but potent danger must threaten him. He went out and opened the door, leaving it ajar. No sound reached him from the stairs.

He sat down again in a deep, red leathern armchair and waited.

How long he waited he could not, afterwards, say (probably less than five minutes) before anything occurred. He listened to the silence of Mayfair around him, and throughout that time nothing disturbed it but a rare footstep, and once the passing of a taxi.

Then, he heard something else.

Someone was coming upstairs—softly, hesitantly.

Donovan’s first impulse was to hurry out to greet the new arrival. His second, oddly enough, was to close the door.

He could never account, then or later, for that nervous premonition which claimed him. Of his neighbours he knew nothing. The person coming upstairs might be a fellow resident. But of one thing he felt assured: It was not Steel Maitland.

And so what he did was this:

He remained seated in the red armchair, staring across the lobby at the partly open door. Those soft, almost furtive footsteps, drew nearer.

On the landing they ceased. Whoever stood there had been arrested by the light shining out.

He sat quite still. And as he sat there he saw the door slowly open wider. A panel of blackness which represented the unlighted landing increased in width. There was no sound, now.

Putting his cigarette in a tray. Donovan was leaning forward, gripping the chair arms, and prepared to spring to his feet, when the door opened fully… and a girl took one faltering step into the lobby!

2

Donovan did not spring up; he rose slowly, watching her where she stood. Her face was in partial shadow, so that he could not determine the colour of a mass of distractingly curly hair; but of the fact that his visitor was of quite unusual beauty there could be no doubt whatever. Her eyes were magnificent, fixed wildly in a stare of dreadful perplexity; her lips were slightly parted. With one hand she held about her a wrap or cloak which Donovan recognised as that lure of souls, mink, and which therefore must have been worth several thousand pounds. Slim legs (revealed, as he thought at the time, in gossamer stockings of a quality no longer purchasable in London) were of equally patrician elegance, but he was puzzled to note that she wore blue slippers trimmed around the ankles with white fur.

These impressions he derived in one swift glance as he stood up. Then, trying to speak gently:

“I hope I have not alarmed you,” he said.

Her expression changed scarcely at all. She shrank back to the door, upon which one hand still rested; and as the upraised arm was bare, Donovan assumed that his mysterious caller wore evening dress. She moistened her lips, and drew the fur wrap more closely around her.

“No,” she whispered; “it is … my fault.”

And as she stood there, watching him in that distraught way, Donovan saw that she trembled violently. He realised that this beautiful mystery was in a state of acute terror, of exhaustion, was, in fact, on the verge of collapse. He took a step forward.

“Please sit down and rest. You are quite safe here. What has frightened you?”

She shrank away yet further. Indeed, perhaps she would have tried to escape, if, as she retreated, the door had not been closed by her own movement, so that she was left standing with her back to it.

“Thank you—no. I… quite understand.” Her words were barely audible; her expression was that of a trapped animal. Not unnaturally, perhaps, Donovan misconstrued her terror, and, frankly, resented it; but when he spoke again he still spoke gently.

“I shouldn’t have left the door ajar. And when I heard you outside I shouldn’t have remained silent. I was just expecting someone else—that’s all. Surely you can see its simply a mistake?”

But she repelled him, pressing back against the panels wildly.

“I can see,” she whispered, “that you were expecting me… Waiting for me. I might have known she would guess. Very well. Take me back.”

Donovan’s original resentment left him. This girl’s terror—anguish—lay deeper than he had suspected. She had grown alarmingly pale. He determined to make a final effort. “Please try to be calm. How could I be expecting you when I have never seen you in my life before?” She sought to control her trembling lips. “This is my aunt’s flat,” she panted—“although all her things are not here now. If She had not sent you, how could you be here?”

“She?” (Donovan began, now, to doubt the girl’s sanity. To whom did her words refer? The appalling idea occurred to him that him that she had escaped from a mental clinic} “I can’t even imagine what you mean. This is certainly Lady Orpsley’s flat…”

“Lady Orpsley is my aunt.”

“Good heavens!” he exclaimed, and experienced a welcome wave of relief. “Now I see it all! You didn’t know? Well, sit down No, please don’t look so frightened. This flat was leased for me by a mutual friend. I have occupied it just three days. I am Mark Donovan, of the Alliance Press Association, and I only returned to England last Thursday. Surely you understand?”

And as he talked, striving desperately to put his visitor at her ease, those great haunted eyes studied him, and he thought that she was beginning to lose some of her terror; but she held her place by the door, clasping the fur wrap about her with white fingers which trembled.

“Oh,” she murmured, “can it be true.” There was that in her glance, now, which he could only have described as beseeching.

“It is true. Try to understand that you have nothing to be afraid of. Try to tell me what has happened. Let me help you.”

A moment longer she watched him. All colour had fled from her cheeks, and she swayed as she stood there.

“Oh, my God!” she whispered, “what shall I do…”

Then, almost before he could grasp and support her, she swayed right forward and collapsed in a swoon!

Donovan’s frame of mind became indescribable; his brain was in a tumult. First, he thought that he would carry her to the couch in the living room; then, he decided that he would put a cushion under her head where she lay on the rug, and bring brandy, of which he had a small stock.

Stooping over her (the beauty of her pale face was exquisite, black lashes drooping motionless on white cheeks) he became aware of a faint but pleasant perfume exhaled by the fur; and as he moved her in order to put the cushion in place, her wrap fell away from her shoulders.

Swiftly, Donovan rearranged it. Then he came upright at a bound.

He had made a staggering discovery!

Accounting himself, as he did, a fairly complete cosmopolitan, for he had lived in many of the world’s capitals, the fact remained that up to fourteen he had never moved more than ten miles from a New England farm—and this tells. To that very moment he remained subject to attacks of harrowing embarrassment; and he had one now.

He hurried into his bedroom where he had concealed his two remaining bottles of French brandy (distrusting the daily help who looked after the apartment). Beyond question, he was overwrought, and he couldn’t find the key of the case in which the cognac was locked. A swooning woman always got him jumpy, in any event, and he cursed his shaky nerves when he discovered the missing key in his pocket.

Then he ran into the bathroom, and back again for a corkscrew; so that perhaps three minutes had elapsed before he returned to the lobby carrying a glass of brandy and water.

The lobby was empty!

Noting the door

Comments (0)