His Masterpiece - Émile Zola (ebook reader 8 inch .txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

Book online «His Masterpiece - Émile Zola (ebook reader 8 inch .txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

By Émile Zola.

Translated by Ernest Alfred Vizetelly.

Table of Contents Titlepage Imprint Preface His Masterpiece I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII Endnotes Colophon Uncopyright ImprintThis ebook is the product of many hours of hard work by volunteers for Standard Ebooks, and builds on the hard work of other literature lovers made possible by the public domain.

This particular ebook is based on a transcription produced for Project Gutenberg and on digital scans available at the Internet Archive.

The writing and artwork within are believed to be in the U.S. public domain, and Standard Ebooks releases this ebook edition under the terms in the CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication. For full license information, see the Uncopyright at the end of this ebook.

Standard Ebooks is a volunteer-driven project that produces ebook editions of public domain literature using modern typography, technology, and editorial standards, and distributes them free of cost. You can download this and other ebooks carefully produced for true book lovers at standardebooks.org.

PrefaceHis Masterpiece, which in the original French bears the title of L’Oeuvre, is a strikingly accurate story of artistic life in Paris during the latter years of the Second Empire. Amusing at times, extremely pathetic and even painful at others, it not only contributes a necessary element to the Rougon-Macquart series of novels—a series illustrative of all phases of life in France within certain dates—but it also represents a particular period of M. Zola’s own career and work. Some years, indeed, before the latter had made himself known at all widely as a novelist, he had acquired among Parisian painters and sculptors considerable notoriety as a revolutionary art critic, a fervent champion of that “Open-air” school which came into being during the Second Empire, and which found its first real master in Édouard Manet, whose then-derided works are regarded, in these later days, as masterpieces. Manet died before his genius was fully recognised; still he lived long enough to reap some measure of recognition and to see his influence triumph in more than one respect among his brother artists. Indeed, few if any painters left a stronger mark on the art of the second half of the nineteenth century than he did, even though the school, which he suggested rather than established, lapsed largely into mere impressionism—a term, by the way, which he himself coined already in 1858; for it is an error to attribute it—as is often done—to his friend and junior, Claude Monet.

It was at the time of the Salon of 1866 that M. Zola, who criticised that exhibition in the Événement newspaper,1 first came to the front as an art critic, slashing out, to right and left, with all the vigour of a born combatant, and championing M. Manet—whom he did not as yet know personally—with a fervour born of the strongest convictions. He had come to the conclusion that the derided painter was being treated with injustice, and that opinion sufficed to throw him into the fray; even as, in more recent years, the belief that Captain Dreyfus was innocent impelled him in like manner to plead that unfortunate officer’s cause. When M. Zola first championed Manet and his disciples he was only twenty-six years old, yet he did not hesitate to pit himself against men who were regarded as the most eminent painters and critics of France; and although (even as in the Dreyfus case) the only immediate result of his campaign was to bring him hatred and contumely, time, which always has its revenges, has long since shown how right he was in forecasting the ultimate victory of Manet and his principal methods.

In those days M. Zola’s most intimate friend—a companion of his boyhood and youth—was Paul Cézanne, a painter who developed talent as an impressionist; and the lives of Cézanne and Manet, as well as that of a certain rather dissolute engraver, who sat for the latter’s famous picture Le Bon Bock, suggested to M. Zola the novel which he has called L’Oeuvre. Claude Lantier, the chief character in the book, is, of course, neither Cézanne nor Manet, but from the careers of those two painters, M. Zola has borrowed many little touches and incidents.2 The poverty which falls to Claude’s lot is taken from the life of Cézanne, for Manet—the only son of a judge—was almost wealthy. Moreover, Manet married very happily, and in no wise led the pitiful existence which in the novel is ascribed to Claude Lantier and his helpmate, Christine. The original of the latter was a poor woman who for many years shared the life of the engraver to whom I have alluded; and, in that connection, it as well to mention that what may be called the Bennecourt episode of the novel is virtually photographed from life.

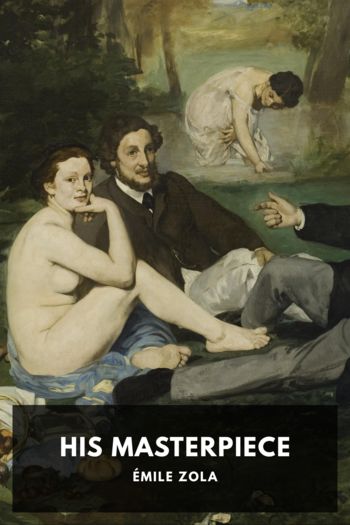

Whilst, however, Claude Lantier, the hero of L’Oeuvre, is unlike Manet in so many respects, there is a close analogy between the artistic theories and practices of the real painter and the imaginary one. Several of Claude’s pictures are Manet’s, slightly modified. For instance, the former’s painting, In the Open Air, is almost a replica of the latter’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (“A Lunch on the Grass”), shown at the Salon of the Rejected in 1863. Again, many of the sayings put into Claude’s mouth in the novel are really sayings of Manet’s. And Claude’s fate, at the end of the book, is virtually that of a moody young fellow who long assisted Manet in his studio, preparing his palette, cleaning his brushes, and so forth. This lad, whom Manet painted in L’Enfant aux Cerises (“The Boy with the Cherries”), had

Comments (0)