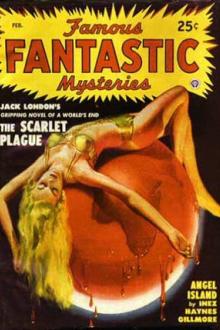

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

was only a blue shimmer; and up and up and up until she was only a dark

dot. Then, without warning, again she dropped, gradually this time,

head-foremost like’ a diver, down and down and down until her body was

perfectly outlined, down and down and down until she floated just above

their heads.

Coming thus slowly upon them, she gave, for the first time, a close view

of her wonderful blondeness. It was a sheer golden blondeness, not a

hint of tow, or flaxen, or yellow; not a touch of silver, or honey, or

auburn. It was half her charm that the extraordinary strength and vigor

of her contours contrasted with the delicacy and dewiness of her

coloring, that from one aspect, she seemed as frail as a flower, from

another as hard as a crystal. She had, at the same time, the untouched,

unstained beauty of the virgin girl, and the hard, muscular strength of

the virgin boy. Her skin, white as a lily-petal and as thick and smooth,

had been deepened by a single drop of amber to cream. Her eyes, of which

the sculpturesque lids drooped a little, flashed a blue as limpid as the

sky. Teeth, set as close as seed-pearls, gleamed between lips which were

the pink of the faded rose. The sunlight turned her golden hair to spun

glass, melted it to light itself. The shadow thickened it to fluid,

hardened it to massy gold again. The details of her face came out only

as the result of determined study. Her chief beauty - and it amounted to

witchery, to enchantment - lay in a constant and a constantly subtle

change of expression.

During this exhibition the men stood frozen in the exact attitudes in

which she found them. Ralph Addington alone remained master of himself.

He stood quiet, every nerve tense, every muscle alert, the expression on

his face that of a cat watching a bird. At her second dip downward, he

suddenly jumped into the air, jumped so high that his clutching fingers

grazed her finger-tips.

That frightened her.

Her upward flight was of a terrific speed - she leaped into the sky.

But once beyond the danger-line her composure came back. She dropped on

them a coil of laughter, clear as running water, contemptuous,

mischievous. Still laughing, she sank again, almost as near. Her mirth

brought her lids close together. Her eyes, sparkling between thick files

of golden lash, had almost a cruel sweetness.

She immediately flew away, departing over the water. Ralph cursed

himself for the rest of the day. She returned before the week was out,

however, and, after that, she continued to visit them at intervals of a

few days. The sudden note of blue, even in the distance it seemed to

connote coquetry, was the signal for all the men to stop work. They

could not think clearly or consecutively when she was about. She was one

of those women whose presence creates disturbance, perturbation, unrest.

The very sunshine seemed alive, the very air seemed vibrant with her.

Even when she flew high, her shadow came between them and their work.

“She sure qualifies when it comes to fancy flying,” said Honey Smith.

“She’s in a class all by herself.”

Her flying was daring, eccentric, temperamental, the apotheosis of

brilliancy - genius. The sudden dart up, the terrifying drop down seemed

her main accomplishment. The wonder of it was that the men could never

tell where she would land. Did it seem that she was aiming near, a

sudden swoop would bring her to rest on a faraway spot. Was it certain

that she was making for a distant tree-top, an unexpected drop would

land her a few feet from their group. She was the only one of the

flying-girls who touched the earth. And she always led up to this feat

as to the climax of what Honey called her “act.” She would drop to the

very ground, pose there, wavering like an enormous butterfly, her great

wings opening and shutting. Sometimes, tempted by her actual nearness

and fooled by her apparent weakness, the five men would make a rush in

her direction. She would stand waiting and drooping until they were

almost on her. Then in a flash came the tremendous whirr of her start,

the violent beat of her whipping progress - she had become a blue speck.

She wore always what seemed to be gossamer, rose-color in one light,

sky-color in another; a flexible film that one moment defined the long

slim lines of her body and the next concealed them completely. Near, it

could be seen that this drapery was woven of tiny buds, pink and blue;

afar she seemed to float in a shimmering opalescent mist.

She teased them all, but it was evident from the beginning that she had

picked Ralph to tease most. After a long while, the others learned to

ignore, or to pretend to ignore, her tantalizing overtures. But Ralph

could look at nothing else while she was about. She loved to lead him in

a long, wild-goose chase across the island, dipping almost within reach

one moment, losing herself at the zenith in another, alighting here and

there with a will-o’-the-wisp capriciousness. Sometimes Ralph would

return in such an exhausted condition that he dropped to sleep while he

ate. At such times his mood was far from agreeable. His companions soon

learned not to address him after these expeditions.

One afternoon, exercising heroic resolution, Ralph allowed Peachy to

fly, apparently unnoticed, over his head, let her make an unaccompanied

way half across the island. But when she had passed out of earshot he

watched her carefully.

“Say, Honey,” he said after half an hour’s fidgeting, “Peachy’s settled

down somewhere on the island. I should say on the near shore of the

lake. I don’t know that anything’s happened - probably nothing. But I

hope to God,” he added savagely, “she’s broken a wing. Come on and find

out what she’s up to, will you?”

“Sure!” Honey agreed cheerfully. “All’s fair in love and war. And this

seems to be both love and war.”

They walked slowly, and without talking, across the beach. When they

reached the trail they dropped on all fours and pulled themselves

noiselessly along. The slightest sound, the snapping of a twig, the

flutter of a bird, brought them to quiet. An hour, they searched

profitlessly.

Then suddenly they got sound of her, the languid slap of great wings

opening and shutting. She had not gone to the lake. Instead, she had

chosen for her resting-place one of the tiny pools which, like pendants

of a necklace, partially encircled the main body. She was sitting on a

flat stone that projected into the water. Her drooped blue wings,

glittering with moisture, had finally come to rest; they trailed behind

her over the gray boulder and into a mass of vivid green water-grasses.

One bare shoulder had broken through her rose-and-blue drapery. The odor

of flowers, came from her. Her hair, a braid over each breast, oozed

like ropes of melted gold to her knees. A hand held each of these

braids. She was evidently preoccupied. Her eyelids were down. Absently

she dabbled her white feet in the water. The noise of her splashing

covered their approach. The two men signaled their plans, separated.

Five minutes went by, and ten and fifteen and twenty. Peachy still sat

silent, moveless, meditative. Not once did she lift her eyelids.

Then Addington leaped like a cat from the bushes at her right.

Simultaneously Honey pounced in her direction from the left.

But - whir-r-r-r - it was like the beating of a tremendous drum.

Straight across the pond she went, her toes shirring the water, and up

and up and up - then off. And all the time she laughed, a delicious,

rippling laughter which seemed to climb every scale that could carry

coquetry.

The two men stood impotently watching her for a moment. Then Honey broke

into roars of delight. “Oh, you kid!” he called appreciatively to her.

“She had her nerve with her to sit still all the time, knowing that we

were creeping up on her, didn’t she?” He turned to Ralph.

But Ralph did not answer, did not hear. His face was black with rage. He

shook his fist in Peachy’s direction.

Of the flying-girls, there remained now only one who held herself aloof,

the “quiet one.” It was many weeks before she visited the island. Then

she came often, though always alone. There was something in her attitude

that marked her off from the others.

“She doesn’t come because she wants to,” Billy Fairfax explained. “She

comes because she’s lonely.”

The “quiet one” habitually flew high and kept high, so high indeed that,

after the first excitement of her tardy appearance, none but Billy gave

her more than passing attention. Up to that time Billy had been a hard,

a steady worker. But now he seemed unable to concentrate on anything. It

was doubtless an extra exasperation that the “quiet one” puzzled him.

Her flying seemed to be more than a haphazard way of passing the time.

It seemed to have a meaning; it was almost as if she were trying to

accomplish something by it; and ever she perfected the figure that her

flight drew on the sky. If she soared and dropped, she dropped and

soared. If she curved and floated, she floated and curved. If she dipped

and leaped, she leaped and dipped. All this he could see. But there were

scores of minor evolutions that appeared to him only as confused motion.

One thing he caught immediately. Those lonely gyrations were not the

exercise of the elusive coquetry which distinguished Peachy. It was more

that the “quiet one” was pushed on by some intellectual or artistic

impulse, that she expressed by the symbols, of her complicated flight

some theory, some philosophy of life, that she traced out some artless

design, some primary pattern of beauty.

Julia always seemed to shine; she wore garments of gleamy-petalled,

white flowers, silvery seaweeds, pellucid marsh-grasses, vines, golden

or purple, that covered her with a delicate lustre. Her wings were

different from the others; theirs flashed color, but hers gave light;

and that light seemed to have run down on her flesh.

“What the thunder is she trying to do up there?” Ralph asked one day,

stopping at Billy’s side. Ralph’s question was not in reality begotten

so much of curiosity as of irritation. From the beginning the “quiet

one” had interested him least of any of the flying-girls as, from the

beginning, Peachy had interested him most.

“I don’t know, of course.” Billy spoke with reluctance. It was evident

that he did not enjoy discussing the “quiet one” with Ralph. “At first

my theory was that flying was to her what dancing is to most girls. But,

somehow, it seems to go deeper than that - as if it were art, or even

creation. Anyway, there’s a kind of bi-lateral symmetry about everything

she does.”

Billy fell into the habit, each afternoon, of strolling away from the

rest, out of sound of their chaff. On the grassy top of one of the

reefs, he found a spot where he could lie comfortably and watch the

“quiet one.” He used to spin long day-dreams there. She looked so remote

far up in the boiling blue, and so strange, that he had an inexplicable

sensation of reverence.

Now it was as though, in watching that aerial weaving and interweaving,

he were assisting at a religious rite. He liked it best when the white

day-moon was afloat. If he half-shut his eyes,

Comments (0)