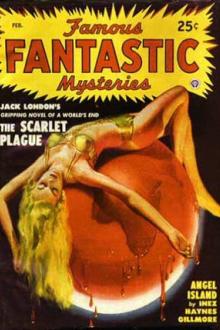

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

rallied and harried him, especially about the poem; but he could always

silence them with a threat to read it aloud. All the Celt in him had

come to the surface. They heard him chanting his numbers in the depths

of the forest; sometimes he intoned them, swinging on the branch of a

high tree. He even wandered over the reefs, reciting them to the waves.

One day, late in the afternoon, Billy lay on his favorite spot on the

southern reef, dreaming. High up in the air, Julia flashed and gyrated,

revolved and spun. It seemed to Billy that he had never seen her go so

high. She looked like a silver feather. But as he looked, she went

higher and higher, so high that she disappeared vertically.

A strange sense of loneliness fell on Billy. This was the first time

since she had begun to come regularly to the island that she had cut

their tryst short. He waited. She did not appear. A minute went by.

Another and another and another. His sense of loneliness deepened to

uneasiness. Still there was no sign of Julia. Uneasiness became alarm.

Ah, there she was at last - a speck, a dot, a spot, a splotch. How she

was flying! How - .

Like a bullet the conviction struck him.

She was falling!

Memories of certain biplanic explorations surged into his mind. “She’s

frozen,” he thought to himself. “She can’t move her wings!” Terror

paralyzed him; horror bound him. He stood still-numb, dumb, helpless.

Down she came like an arrow. Her wings kept straight above her head,

moveless, still. He could see her breast and shoulders heave and twist,

and contort in a fury of effort. Underneath her were the trees. He had a

sudden, lightning-swift vision of a falling aviator that he had once

seen. The horror of what was coming turned his blood to ice. But he

could not move; nor could he close his eyes.

“Oh, God! Oh, God! Oh, God!” he groaned. And, finally, “Oh, thank God!”

Julia’s wings were moving. But apparently she still had little control

of them. They flapped frantically a half-minute; but they had arrested

her fall; they held her up. They continued to support her, although she

beat about in jagged circles. Alternately floating and fluttering, she

caught on an air-current, hurled herself on it, floated; then, as though

she were sliding through some gigantic pillar of quiet air, sank

earthwards. She seized the topmost bough of one of the high trees, threw

her arms across it and hung limp. She panted; it seemed as if her

breasts must burst. Her eyes closed; but the tears streamed from under

her eyelids.

Billy ran close. He made no attempt to climb the tree to which she

clung, so weakly accessible. But he called up to her broken words of

assurance, broken phrases of comfort that ended in a wild harangue of

love and entreaty.

After a while her breath came back. She pulled herself up on the bough

and sat huddled there, her eyelids down, her silvery fans drooping, the

great mass of her honey-colored hair drifting over the green branches,

her drapery of white lilies, slashed and hanging in tatters, the tears

still streaming. Except for its ghastly whiteness, her face showed no

change of expression. She did not sob or moan, she did not even speak;

she sat relaxed. The tears stopped flowing gradually. Her eyelids

lifted. Her eyes, stark and dark in her white face, gazed straight down

into Billy’s eyes.

And then Billy knew.

He stood moveless staring up at her; never, perhaps, had human eyes

asked so definite a question or begged so definite a boon.

She sat moveless, staring straight down at him. But her eyes continued

to withhold all answer, all reassurance.

After a while, she stirred and the spell broke. She opened and shut her

wings, half a dozen times before she ventured to leave her perch. But

once, in the air, all her strength, physical and mental, seemed to come

back. She shook the hair out of her eyes. She pulled her drapery

together. For a moment, she lingered near, floating, almost moveless,

white, shining, carved, chiseled: like a marvelous piece of aerial

sculpture. Then a flush of a delicate dawn-pink came into her white

face. She caught the great tumbled mass of hair in both hands, tied it

about her head. Swift as a flash of lightning, she turned, wheeled,

soared, dipped. And for the first time, Billy heard her laugh. Her

laughter was like a child’s - gleeful. But each musical ripple thrust

like a knife into his heart.

He watched her cleave the distance, watched her disappear. Then,

suddenly, a curious weakness came over him. His head swam and he could

not see distinctly. Every bone in his body seemed to repudiate its

function; his flexed muscles slid him gently to the earth. Time passed.

After a while consciousness came back. His dizziness ceased. But he lay

for a long while, face downward, his forehead against the cool moss.

Again and again that awful picture came, the long, white, girl-shape

shooting earthwards, the ghastly, tortured face, the frenzied, heaving

shoulders. It was to come again many times in the next week, that

picture, and for years to make recurrent horror in his sleep.

He returned to the camp white, wrung, and weak. Apparently his

companions had been busy at their various occupations. Nobody had seen

Julia’s fall; at least nobody mentioned it. After dinner, when the

nightly argument broke into its first round, he was silent for a while.

Then, “Oh, I might as well tell you, Frank, and you, Pete,” he said

abruptly, “that I’ve gone over to the other side. I’m for capture,

friendship by capture, marriage by capture - whatever you choose to call

it - but capture.”

The other four stared at him. “What’s happened to you and Ju - ” Honey

began. But he stopped, flushing.

Billy paid no attention to the bitten-off end of Honey’s question.

“Nothing’s happened to me,” he lied simply and directly. “I don’t know

why I’ve changed, but I have. I think this is a case where the end

justifies the means. Women don’t know what’s best for them. We do.

Unguided, they take the awful risks of their awful ignorance. Moreover,

they are the conservative sex. They have no conscious initiative. These

flying-women, for instance, have plenty of physical courage but no

mental or moral courage. They hold the whip-hand, of course, now.

Anything might happen to them. This situation will prolong itself

indefinitely unless - unless we beat their cunning by our strategy.” He

paused. “I don’t think they’re competent to take care of themselves. I

think it’s our duty to take care of them. I think the sooner - .” He

paused again. “At the same time, I’m prepared to keep to our agreement.

I won’t take a step in this matter until we’ve all come round to it.”

“If it wasn’t for their wings,” Honey said.

Billy shuddered violently. “If it wasn’t for their wings,” he agreed.

Frank bore Billy’s defection in the spirit of classic calm with which he

accepted everything. But Pete could not seem to reconcile himself to it.

He was constantly trying to draw Billy into debate.

“I won’t argue the matter, Pete,” Billy said again and again. ” I can’t

argue it. I don’t pretend even to myself that I’m reasonable or logical,

or just or ethical. It’s only a feeling or an instinct. But it’s too

strong for me. I can’t fight it. It’s as if I’d taken a journey drugged

and blindfolded. I don’t know how I got on this side - but I’m here.”

The effect of this was to weaken a little the friendship that had grown

between Billy and Pete. Also Honey pulled a little way from Ralph and

slipped nearer to his old place in Billy’s regard.

But now there were three warring elements in camp. Honey, Ralph, and

Billy hobnobbed constantly. Frank more than ever devoted himself to his

reading. Pete kept away from them all, writing furiously most of the

day.

“We’re going to have a harder time with him than with Frank,” Billy

remarked once.

“I guess we can leave that matter to take care of itself,” Ralph said

with one of his irritating superior smiles. “How about it, Honey?”

“Surest thing you know,” Honey answered reassuringly. All you’ve got to

do is wait - believe muh!”

“It does seem as if we’d waited pretty long,” Honey himself fumed two

weeks later, “I say we three get together and repudiate that agreement.”

“That would be dishonorable,” Billy said, “and foolish. You can see for

yourself that we cannot stir a step in this matter without co-operation.

As opponents, Pete and Frank could warn the girls off faster than we

could lure them on.”

“That’s right, too,” agreed Honey. “But I’m damned tired of this,” he

added drearily. “Not more tired than we are,” said Billy.

An incident that varied the monotony of the deadlock occurred the next

day. Pete Murphy packed up food and writing materials and, without a

word, decamped into the interior. He did not return that day, that

night, or the next day, or the next night.

“Say, don’t you think we ought to go after him,” Billy said again and

again, “something may have happened.”

And, “No!” Honey always answered. “Trust that Dogan to take care of

himself. You can’t kill him.”

Pete worked gradually across the island to the other side. There the

beach was slashed by many black, saw-toothed reefs. The sea leaped up

upon them on one side and the trees bore down upon them on the other.

The air was filled with tumult, the hollow roar of the waves, the

strident hum of the pines. For the first day, Pete entertained himself

with exploration, clambering from one reef to another, pausing only to

look listlessly off at the horizon, climbing a pine here and there,

swinging on a bough while he stared absently back over the island. But

although his look fixed on the restless peacock glitter of the sea, or

the moveless green cushions that the massed trees made, it was evident

that it took no account of them; they served only the more closely to

set his mental gaze on its half-seen vision.

The second morning, he arose, bathed, breakfasted, lay for an hour in

the sun; then drew pencil and paper from his pack. He wrote furiously.

If he looked up at all, it was only to gaze the more fixedly inwards.

But mainly his head hung over his work.

In the midst of one of these periods of absorption, a flower fell out of

the air on his paper. It was a brilliant, orange-colored tropical bloom,

so big and so freshly plucked that it dashed his verse with dew. For an

instant he stared stupidly at it. Then he looked up.

Just above him, not very high, her green-and-gold wings spread broad

like a butterfly’s, floated Clara. Her body was sheathed in green vines,

delicately shining. Her hair was wreathed in fluttering yellow

orchid-like flowers, her arms and legs wound with them. She was flying

lower than usual. And, under her wreath of flowers, her eyes looked

straight into his.

Pete stared at her stupidly as he had stared at the flower. Then he

frowned. Deliberately he dropped his eyes. Deliberately he went on

writing.

Whir-r-r-r-r! Pete looked up again. Clara was beating back over the

island, a tempest of green-and-gold.

Again, he concentrated on his work.

Pete wrote all

Comments (0)