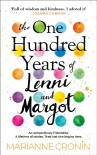

The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗

- Author: Marianne Cronin

Book online «The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗». Author Marianne Cronin

Father Arthur moved smartly to the front of the church and paused for a moment to take us both in. His flock. His sheep. Just waiting to be welcomed into the woolly fold of Jesus’ love.

‘Welcome,’ he said.

And I took it in. The words, the music, everything. And I didn’t even laugh when the old man on the front row’s head bobbed forward as he fell asleep. But then he snored, loudly. A rasping inhalation that was suddenly broken when his head shot up and he shouted ‘Theodore?!’ And then, I did laugh. And Father Arthur laughed too.

Margot and President Ho Chi Minh

MARGOT WAS WEARING lilac. The sunlight hit the tops of the desks around her and made her look like she was shining.

‘You’ll like this one,’ she said, sharpening her pencil and blowing the shavings from her canvas.

Without really appearing to think about it, she started drawing ovals on the page, rows and rows of them. Slowly, the ovals were gifted with shoulders, and two tall buildings rose up on either side of them. Then they were given clothes and faces and signs. And then they were given a story.

London, 18th March 1968, 1 a.m.

Margot Macrae is Thirty-Seven Years Old

I sat on the steps that led up to the front door of our house, bleeding scratches like tallies on my arms, the skin on my left knee having flapped back and revealed something raw and bloody underneath, my right kneecap swelling into a dark, lumpy bruise. My palms were encrusted with tiny pieces of gravel that I tried to unpick with my fingernails, but that only tore at the skin and made it bleed.

It was dark. And cold. But still I waited.

I hadn’t eaten since breakfast the previous morning and my stomach reminded me. For a moment, it felt like it had when Davey was swimming within me and almost ready to meet the world, and he had turned the right side up to begin the journey.

I had been sitting on the cold stone steps for so long that my bottom had gone completely numb. My hair was dirty. My clothes were dirty too, and I was tired in a way that I hadn’t been since Davey passed.

I supposed, though, that the steps were as good a place as any to wait. The next train out of London wouldn’t be until 6 a.m.

Two suitcases waited beside me. I pulled a jumper from inside one of them and draped it around my shoulders. I wouldn’t put it on until later because I didn’t want the blood to stain the sleeves.

I had promised myself there would be no more protests, no more law breaking, no more activism, and yet I’d found myself standing in Trafalgar Square on 17th March 1968, with my heartbeat humming in my ears and my hands shaking. Hoping it would make Meena notice me.

The Professor was there again. In fact, The Professor had become a staple in our lives. He had got much better at remembering to take off his wedding ring. From our flat window, I would watch him. He would pull at it, twisting and twisting (he was obviously a thinner man when he got married) until it came off, and then he would tuck it into his left blazer pocket for safekeeping.

That day in March was their first trip out together in public. Meena was excited. The Professor was smoking and trying to affect an attitude of calm, but he was clearly as nervous as I was. He had on a pair of rounded silver sunglasses, presumably hoping he wouldn’t be recognized by anybody while he held on to the hand of a woman who wasn’t his wife.

We were standing in what was once Trafalgar Square. Only, it wasn’t Trafalgar Square any more; it was a hive of people. The crowd buzzed and jostled and pushed. Two men held a wooden sign with a picture of a smiling President Ho Chi Minh, and underneath a message to the American army: Go home! They shoved past me and forced their way forwards to get closer to the action. Adam and Lawrence were somewhere in the crowd too, wearing T-shirts that said in messy black marker: You can tell Uncle Sam we won’t go to Vietnam.

In the darkness, on the steps, I waited.

I patted my bloodied knee with the flannel I’d brought from upstairs. It stung so much that I pulled it back off quickly, and the last wet bit of skin tore off too. The flesh underneath was pink and shining. But much as it hurt, I didn’t move.

In the half-light of the lamp posts at the end of the road, I saw a figure walking along the pavement. I strained my eyes, but it wasn’t her.

The noise was impossible. It was time to move to Grosvenor Square for the actress to deliver the letter. It was immediate – the tide of people turning.

‘I’m going,’ The Professor said, dropping his cigarette on the ground and not bothering to extinguish it.

Meena stared at him. ‘What?’ she said. ‘You can’t go now, it’s just about to get good.’ But he gave her a smart kiss on the cheek and then elbowed his way through the crowd, telling a woman to back off as she waved a sign in his shaded eyes.

Meena stopped. So did I. She looked like she might cry. Her petulant face set something in me on fire.

She turned to me and she must have seen it, because she asked me, ‘What?’

The crowd was getting louder and swelling around us. There was no way out.

‘Stop it, Meena,’ I shouted. ‘Just stop it.’

The people flowed around us on either side. In the middle of the

Comments (0)